Partner Anna Graf

Queer Places:

Hollywood Plaza Hotel, 1633-1637 Vine St, Los Angeles, CA 90028

Jane Loring (June 6, 1890 - March 15, 1983) was an American film editor and producer active during the 1920s

through the 1940s. She was the first woman ever to cut a motion picture.

By so doing she opened up that branch to women.

Jane Loring, a "mannish" movie editor believed to be a lesbian, became

very close to Katharine

Hepburn.

Jane Loring (June 6, 1890 - March 15, 1983) was an American film editor and producer active during the 1920s

through the 1940s. She was the first woman ever to cut a motion picture.

By so doing she opened up that branch to women.

Jane Loring, a "mannish" movie editor believed to be a lesbian, became

very close to Katharine

Hepburn.

Little is known about Loring's early life, although she later told journalists she broke away from her parents when she was just 13.[2] Born in Denver, Loring decided when she was 16 that she wanted to become a director.[3][4] Her mother, according to her death certificate, was named Clara Logan; no information was given about her father.

She was also an accomplished violinist, and it was this talent that took her to New York City.[2] While in NYC, she performed in an orchestra and also took on stage roles.[4][5] She'd later appear as an actress in a number of silent films.

Married very briefly to the pioneer film director Lansdale Hanshaw (divorced in 1924), Loring decamped to Hollywood on her own, taking a room at the Plaza Hotel on Vine Street. She secured a position as a stenographer for Al Kaufman, general manager of the Grauman theaters; she then moved onto a script-girl position.[4] From there it was a quick leap onto the Paramount lot, where a friendship with Dorothy Arzner brought her into the cutting room.

Before joining Famous Players-Lasky's editing staff in 1926, she edited movie trailers. In the early 1930s, she moved to RKO, where she edited films and worked as Pandro S. Berman's right-hand woman, sometimes working as an assistant director.[6] She was good friends with Katharine Hepburn and edited many of Hepburn's films.[7][8] Loring and Kate met on Break of Hearts, when the attractive film technician was hired as an assistant film editor to William Hamilton. Three months later, she had progressed to editor on Alice Adams. Loring edited Kate's next three films, during which time she became her close adviser. “I remember how friendly Hepburn got with Jane Loring,” said Jean Howard, present on the set of Break of Hearts when the two women met. “There was a whole circle around [Loring] of women who were very masculine, and Hepburn was a part of it.”

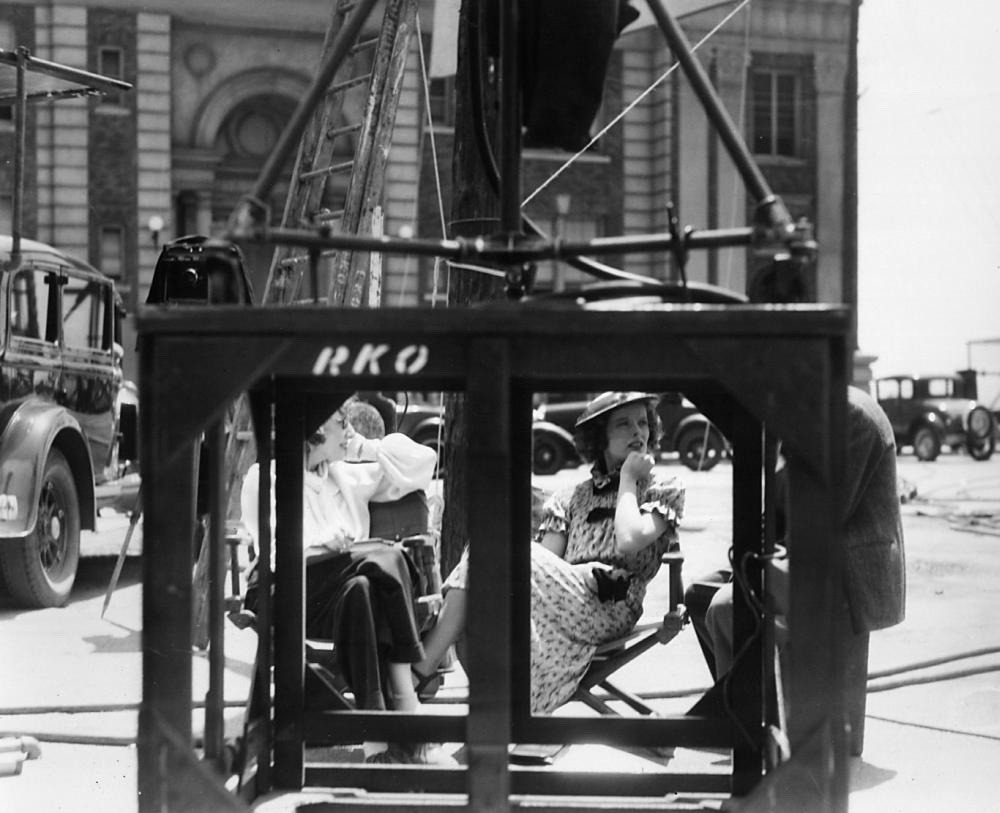

Katharine Hepburn with film editor friend Jane Loring, on the RKO

lot/set of Alice Adams, which premiered in 1935

She used to wear slacks and overcoats and men’s hats ... She was very good with details, talking to people and working things out. Hepburn liked her and would listen to her. Jane became a trusted conduit between producer and star. She’d give Kate some time to digest things and think about them and then Dad would talk to her. Jane was [good at] smoothing things.

In her beret and rubber-soled shoes, Jane hurried about the set, speaking only when necessary, huddling with Berman then rushing to confer with Kate. In winter she invariably wore blue trousers, in summer white flannel slacks. “She is so busy,” one reporter surmised, “she has no time to buy dresses.”

Loring made no pretense about being a lesbian. “She was as obvious as one could be,” recalled Jean Howard, who worked with her on Break of Hearts—an opinion confirmed by those who knew Loring later in life. “She was very forthright,” said one friend. “She might not have shouted it from rooftops, but she didn’t need to. It was plain and clear.”

Indeed, the cutting room was traditionally a very hospitable place for freethinking women, an oasis of opportunity in an otherwise sexist system. Dorothy Arzner had also started out as an editor, mentored herself by an older woman. Columnists spotted Loring sharing a hamburger at a drive-in with Arzner and hunkered down on the lot with Eda Warren, another “single miss” from the cutting room. Another time, she was observed strolling with Fred de Gresac, one of the most overt lesbians in the film colony, with her men’s ties and short-cropped, flaming red hair. On her own from a young age, forced to earn a living for herself, Loring fit a model identified by the historian Lillian Faderman: the self-identified lesbian. Socially and economically independent from a husband or family, these women “could live out [their] attachment to women for the rest of [their lives].”

Sometime after Laura Barney Harding’s departure, in between all the stories about marrying Leland Hayward, Kate began an ardent companionship with Jane Loring. Jean Howard called them “inseparable.” Forty years later, for the author Charles Higham, Loring herself would recall sitting with Kate in a field weaving daisies through each other’s hair—a lovely little reverie, though Higham chose not to include it in his own biography of Hepburn. But the friendship didn’t go unnoticed by the press; Modern Screen commented on how much time the two spent together. George Stevens, in fact, thought Loring exerted undue influence over Kate, who turned to her new friend for advice in the way she had once done with Laura.

Whether their affair was of the heart or the flesh—or both—is impossible to know. Certainly Loring, even at forty-four, was the physical type of woman Kate always seemed to prefer: slim and boyish. What’s undeniable is that for much of 1935, Kate and Jane were devoted to each other.

According to Alan Royle, in 1937 Kate Hepburn moved in with Howard Hughes at Muirfield Mansion in Los Angeles. Hughes usually slept in his study so Kate was allocated his former wife’s master bedroom. It was not lost on Kate that the only person who regularly shared his bed while she was living there was Cary Grant, who slept over about twice a week. At the time Hepburn was still sleeping intermittently with directors George Stevens and John Ford and her girlfriend Jane Loring, all without Hughes’ knowledge. He did not spy on Kate as he later would on Ava Gardner when she entered his life. Quite simply, sexually, the Hughes-Hepburn relationship held little interest for either of them. They just enjoyed each other’s company – while it lasted anyway.

Loring’s friend Teddy Smith, who knew her in the 1970s, recalled a photo of Kate on Loring’s table and notes from the star bundled in a drawer. “Jane told me Hepburn was very special to her,” Smith said. “Their affair was wonderful, but she understood when Hepburn had to end it. Jane could live the way she wanted, but Hepburn had an image to maintain.”

For her part, Jane Loring would find another companion, Anna Graf, sister of the movie producer William Graf (Lawrence of Arabia, A Man for All Seasons), with whom she shared her life and who inherited the bulk of her estate when she died in 1983 at the age of ninety-two. Graf, “a very private person,” according to her attorney, left boxes of old papers in storage at the time of her death in 1993. These were destroyed, leaving unanswered the question of whether they contained Hepburn’s letters to Loring. The lawyer who handled Loring’s estate, Noel Hatch, was also Dorothy Arzner’s lawyer.

My published books: