Queer Places:

6 Rue des Beaux Arts, 75006 Paris, France

James

Lord (November 27, 1922 – August 23, 2009) was an intimate of Picasso and

Giacometti whose biographies and memoirs provide a vivid picture of the artistic milieu of Montparnasse after World War II.

James

Lord (November 27, 1922 – August 23, 2009) was an intimate of Picasso and

Giacometti whose biographies and memoirs provide a vivid picture of the artistic milieu of Montparnasse after World War II.

Lord, while serving with Army intelligence during the war, traveled to Paris on a three-day pass in December 1944 and made a beeline to Picasso’s studio on the Rue des Grands-Augustins. There he gained entry into the artistic set in Montparnasse. Returning to Paris after the war, he became a kind of Boswell to the artistic and social elite in France and, to a lesser extent, Britain. In three volumes of memoirs, he left sharp portraits of Gertrude Stein, Jean Cocteau, Balthus, Peggy Guggenheim and other figures encountered in studios, cafes and salons. He wrote several important works on Giacometti, notably the definitive “Giacometti: A Biography,” and “Picasso and Dora,” a memoir dealing with the artist and his longtime mistress and muse Dora Maar. All of Lord’s many encounters, it seemed, left an impression, which he turned into pithy vignettes, like the one involving Balthus and Giacometti that he recounted in “A Gift for Admiration.” “I recall one afternoon with them at the Café de Flore,” he wrote, “when they argued at length over the perceptible dimensions of Géricault’s ‘Raft of the Medusa’ should it be viewed on the far side of the boulevard, Alberto loudly insisting that at such a distance it would appear to be only a few centimeters in height while Balthus calmly maintained that its appearance would correspond exactly to its actual size because one saw what one knew rather than what one mere hypothesized.”

Lord was born and reared in Englewood, N.J. His father was a stockbroker, and until the Wall Street crash the family lived, as Lord put it, in “the lower echelons of the upper classes.” After attending private schools, he enrolled at Wesleyan University, where he labored without distinction. He was, he confessed, “a poor student, a cheater and malingerer.” Unhappy at college, he enlisted in the Army soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor. As the Normandy invasion drew near, his command of French earned him a posting to the Military Intelligence Service and duty in France as a translator. Lord attended the Army Specialized Training program at Boston College where he was ordered to study everything related to France: its language, culture, history, and customs. This was not hard duty for an intellectual like Lord. As a young gay man, he was also delighted to explore the pleasures offered by World War II Boston. A friend told him about the bar at the Statler Hotel (now Park Plaza). “The lobby was long and high, expensive and gold-plated, busy with war-time visitors. The friend recommended that Lord book a room and then proceed to the bar and pick someone up. ”It was packed with servicemen, several rows deep, standing along the crescent-shaped bar, too many to count…Crowded tight together, jostling back and forth, not one lady…among them.” When he squeezed into the bar, a sailor turned to Lord and said, “Hey, cutie, you must be new. I could blow you out of the water.”

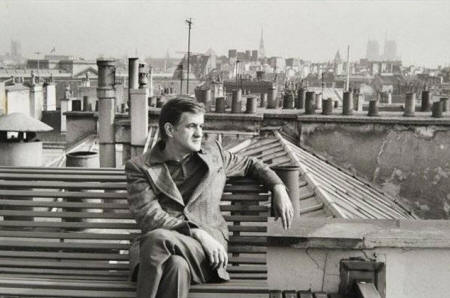

Henri Cartier-Bresson (French, 1908–2004)Title:

James Lord, on the terrace of his apartment, 6 Rue des Beaux-Arts, Paris , 1976Medium:

gelatin silver print

Size:

18.7 x 28.6 cm. (7.4 x 11.3 in.)

Lord cultivated Picasso assiduously and resumed the relationship on his return to Paris in 1947, after leaving Wesleyan without a degree. He set his sights on becoming a writer but spent most of his time and energy socializing, buying art, traveling and living a giddy expatriate life surrounded by artists and aristocrats who may or may not have noticed that he was taking careful notes. “My friends say I am secretive and devious,” he wrote in the preface to “Picasso and Dora.” “They are right.” Two early novels, “No Traveler Returns” (1956), about a rich American traveling in Europe in search of love and happiness, and “The Joys of Success” (1958), set in Hollywood, made little impression on critics or the reading public. On the other hand, “A Giacometti Portrait,” a slim volume published by the Museum of Modern Art in 1965 in conjunction with a retrospective exhibition, established him as an ingratiating, perceptive guide to the artist. “It’s unrivaled in its account of Giacometti in his studio and his working methods,” Anne Umland, a curator at the Museum of Modern Art who helped organize its 2001 Giacometti retrospective, said Wednesday. “I still recommend it to anyone who wants an introduction to Giacometti.” Like Lord’s subsequent work, the Giacometti essay was a curious blend of autobiography, reportage and criticism. Lord had struck up a friendship with the artist in 1952, and his essay was a highly personal account of the 18 sessions he spent sitting for a portrait by the artist, whom he drew out with pointed questions. “You look like a real thug,” Giacometti told him at their first sitting. “If I could paint you as I see you and a policeman saw the picture, he’d arrest you immediately.” Lord returned to Giacometti with “Alberto Giacometti: Drawings” (1971), for which he wrote an introductory essay.

His biographical work gave Lord's life new direction after further novels had been rejected. It proved very slow work, but in 1975 he was encouraged by meeting the 28-year-old Gilles Roy, with whom he subsequently lived, and he was also spurred on by the hope that his mother would live to see the biography published. Although she was over 90 when it finally appeared in 1985, she duly read it three times.

In 1985 he published his full-length biography, 15 years in the writing, to near-universal praise for its subtle delineation of the artist’s conflicted personality and creative struggles. “It is still essential reading for anyone interested in Giacometti,” Umland said. Having finished with Giacometti, Lord embarked on a series of memoirs, told through the notable figures he cultivated, admired and often described in less than flattering terms. (Gertrude Stein, he wrote, “made me think of a burlap bag filled with cement and left to harden.”) The first was “Picasso and Dora: A Personal Memoir” (1993), an exercise in gossip at the highest level. Mr. Lord added his own twist to the complex relationship between artist and muse when, despite his homosexuality, he entered into an affair with Maar. “When with her, one feels at an extraordinary altitude,” he recorded in his diary. Lord continued his autobiographical series with “Six Exceptional Women” (1994), “Some Remarkable Men” (1996) and “A Gift for Admiration” (1998).

At his death he had just completed a fourth volume of memoirs dealing with his experiences in the Army. Titled “My Queer War,” it was scheduled to be published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux in June. The memoir undoubtedly reflected Lord’s slyly pre-emptive approach to the form. “An autobiographer,” he once wrote, “is in the business of doing for himself what he wishes not to be done to him by anyone else.”

Lord died on August 23, 2009, at his home in Paris. He was 86. The cause was a heart attack, said his longtime companion and adopted son, Gilles Roy-Lord.

My published books: