Queer Places:

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Glenwood Cemetery, Natick, Massachusetts 01760, Stati Uniti

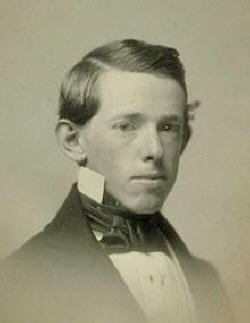

Horatio Alger Jr. (January 13, 1832 – July 18, 1899) was an American

writer, best known for his many young adult novels about impoverished boys and

their rise from humble backgrounds to lives of middle-class security and

comfort through hard work, determination, courage, and honesty. His writings

were characterized by the "rags-to-riches" narrative, which had a formative

effect on America during the Gilded Age.

Horatio Alger Jr. (January 13, 1832 – July 18, 1899) was an American

writer, best known for his many young adult novels about impoverished boys and

their rise from humble backgrounds to lives of middle-class security and

comfort through hard work, determination, courage, and honesty. His writings

were characterized by the "rags-to-riches" narrative, which had a formative

effect on America during the Gilded Age.

All of Alger's juvenile novels share essentially the same theme, known as the "Horatio Alger myth": a teenage boy works hard to escape poverty. Often it is not hard work that rescues the boy from his fate but rather some extraordinary act of bravery or honesty. The boy might return a large sum of lost money or rescue someone from an overturned carriage. This brings the boy—and his plight—to the attention of a wealthy individual.

Alger secured his literary niche in 1868 with the publication of his fourth book, Ragged Dick, the story of a poor bootblack's rise to middle-class respectability. This novel was a huge success. His many books that followed were essentially variations on Ragged Dick and featured casts of stock characters: the valiant hard-working, honest youth, the noble mysterious stranger, the snobbish youth, and the evil, greedy squire.

In the 1870s, Alger's fiction was growing stale. His publisher suggested he tour the American West for fresh material to incorporate into his fiction. Alger took a trip to California, but the trip had little effect on his writing: he remained mired in the tired theme of "poor boy makes good." The backdrops of these novels, however, became the American West rather than the urban environments of the northeastern United States.

In the last decades of the 19th century, Alger's moral tone coarsened with the change in boys' tastes. Sensational thrills were wanted by the public. The Protestant work ethic had loosened its grip on America, and violence, murder, and other sensational themes entered Alger's works. Public librarians questioned whether his books should be made available to the young.[1][2] They were briefly successful, but interest in Alger's novels was renewed in the first decades of the 20th century, and they sold in the thousands. By the time he died in 1899, Alger had published around a hundred volumes. He is buried in Natick, Massachusetts. Since 1947, the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans has awarded scholarships and prizes to deserving individuals.

Scharnhorst writes that Alger "exercised a certain discretion in discussing his probable homosexuality" and was known to have mentioned his sexuality only once after the Brewster incident. In 1870 the elder Henry James wrote that Alger "talks freely about his own late insanity—which he in fact appears to enjoy as a subject of conversation". Although Alger was willing to speak to James, his sexuality was a closely guarded secret. According to Scharnhorst, Alger made veiled references to homosexuality in his boys' books, and these references, Scharnhorst speculates, indicate Alger was "insecure with his sexual orientation". Alger wrote, for example, that it was difficult to distinguish whether Tattered Tom was a boy or a girl and in other instances he introduces foppish, effeminate, lisping "stereotypical homosexuals" who are treated with scorn and pity by others. In Silas Snobden's Office Boy, a kidnapped boy disguised as a girl is threatened with being sent to the "insane asylum" if he should reveal his actual sex. Scharnhorst believes Alger's desire to atone for his "secret sin" may have "spurred him to identify his own charitable acts of writing didactic books for boys with the acts of the charitable patrons in his books who wish to atone for a secret sin in their past by aiding the hero". Scharnhorst points out that the patron in Try and Trust, for example, conceals a "sad secret" from which he is redeemed only after saving the hero's life.[76]

Alan Trachtenberg, in his introduction to the Signet Classic edition of Ragged Dick (1990), points out that Alger had tremendous sympathy for boys and discovered a calling for himself in the composition of boys' books. "He learned to consult the boy in himself", Trachtenberg writes, "to transmute and recast himself—his genteel culture, his liberal patrician sympathy for underdogs, his shaky economic status as an author, and not least, his dangerous erotic attraction to boys—into his juvenile fiction".[77] He observes that it is impossible to know whether Alger lived the life of a secret homosexual, "[b]ut there are hints that the male companionship he describes as a refuge from the streets—the cozy domestic arrangements between Dick and Fosdick, for example—may also be an erotic relationship". Trachtenberg observes that nothing prurient occurs in Ragged Dick but believes the few instances in Alger's work of two boys touching or a man and a boy touching "might arouse erotic wishes in readers prepared to entertain such fantasies". Such images, Trachtenberg believes, may imply "a positive view of homoeroticism as an alternative way of life, of living by sympathy rather than aggression". Trachtenberg concludes, "in Ragged Dick we see Alger plotting domestic romance, complete with a surrogate marriage of two homeless boys, as the setting for his formulaic metamorphosis of an outcast street boy into a self-respecting citizen".[78]

Samuel Barber (1910-1987), Horatio Alger (1832-1899), Charlotte Cushman (1816-1876) and Bill Sherwood (1952-1990), all descend from the same Pilgrims, Degory Priest (arrived with the Mayflower), Isaac Allerton and his wife Mary Morris (arrived with the Mayflower), and Robert Cushman.

Tony

Scupham-Bilton - Mayflower 400 Queer Bloodlines

My published books: