Partner Frederick Demmler

Queer Places:

Richmond, NH 03470

Dublin Town Cemetery

Dublin, Cheshire County, New Hampshire, USA

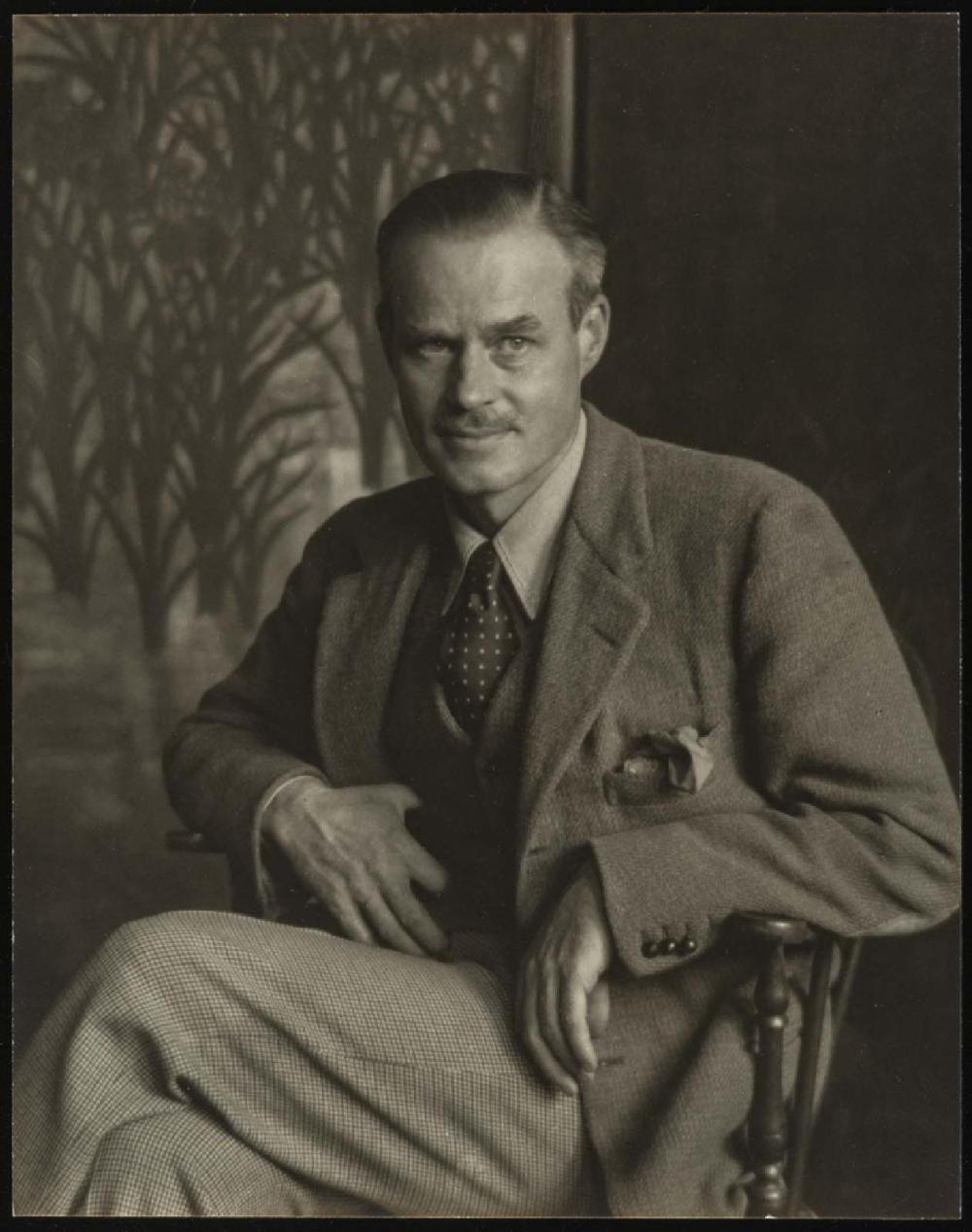

Alexander Robertson James (December 22, 1890 -

February 26, 1946) was a portrait and

landscape painter.

His friends include Barry Faulkner and

Thornton Wilder. He studied with Abbott Handerson Thayer and was a close friend of

John Singer Sargent and Rockwell Kent.

Alexander Robertson James (December 22, 1890 -

February 26, 1946) was a portrait and

landscape painter.

His friends include Barry Faulkner and

Thornton Wilder. He studied with Abbott Handerson Thayer and was a close friend of

John Singer Sargent and Rockwell Kent.

Alexander Robertson James was born in Cambridge, MA, the younger son of psychologist William James (1842-1910), brother of painter William James (1882-1961), and nephew of novelist Henry James. His other siblings include Harry James and Margaret "Peggy" James Porter. Alexander James was actually christened Francis Temple Tweedy James in 1890. In 1925 he had his name officially changed to Alexander Robertson James.

Alexander Robertson James, Mass., CA, NH (1890-1946) Oil on panel (Renaissance Panel with label on reverse) of a young man, signed lower left "Alexander James, 1944", set in a "Thulin" custom frame as incised on the back in 1944, 12" x 19". Good overall condition. Provenance: Edie Clark, Harrisville, NH.

Frederika Paine James by Alexander Robertson James

Robert Allerton frequently accompanied John Sumner Runnells' unmarried daughter, Alice, to the theater and other social events, and he enjoyed the Runnells' hospitality at Willowgate, in Chocorua, New Hampshire, near the home of William James. By 1911, Alice Runnells had become engaged to young William "Billy" James, second son of William and Alice James, an aspiring painter who had often asked her to sit for him in his time at Chocorua. Perhaps disappointed that Roger Quilter failed to join him that summer at The Farms, Allerton followed the Runnells to Willowgate and discovered that the James' youngest child, Alexander Robertson James, then not quite 21, also was determined to become a painter of note.

Having apprenticed himself to Abbot Thayer in that artist's Dublin, New Hampshire, studio for several years, Aleck now wanted more formal training and, following his brother Billy, had gained admission to the School at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. When their time in the north country was up, Allerton offered to escort young James back to the city. Allerton's interest in young Aleck extended at least through the following summer, when, in keeping with the pattern already established, the aspiring painter was invited to stay at The Farms. Aleck was on his way west to experience the frontier life of a dude ranch in Montana, but, at Allerton's request, he first stopped at Monticello in June 1912. While in residence there, Aleck completed a charcoal sketch of his host, now lost, striking enough to impress his uncle Henry James, to whom it was dispatched.

Before he had left Boston for his western tour, Alexander James had befriended a fellow student at the Museum School, a strapping (through socially diffident) young man from Pittsburgh named Frederick Demmler, who became his studio-mate. According to a mutual friend, "The two young painters proceeded to form an offensive and defensive alliance. Where one was, there was the other also... It was good to see the pair together: two thoroughbreds. Both athletes, both artists, one dark, the other fair, both about the same height and build." The observer here was Lucien Price, Harvard-educated art critic for the Boston Evening Transcript, who published this adoring eulogy to his lover the year after Demmler was killed on the Belgian frontier - pathetically, just days before the Armistice was signed in 1918.

"There had been two years in Cornell, before he came to Boston," Price recalled. "He had rowed in his class 8th on Lake Cayuga." Alexander James also was an avid amateur sportsman. Basketball and baseball had been his passions as a schoolboy (certainly not academics - since he suffered from dyslexia, before anyone had a name for it, and failed the Harvard entrance examination no fewer than five times). Like his father, he loved the outdoors and spent much of his time thinking in the woods and hills at Chocorua. Demmler joined Aleck there over their winter vacation in 1913, and as their friendship deepened, they both resolved to join forces by spending the next academic year in Europe: visiting the great galleries and museums, setting up their easels, and learning what they might from the Old (and newer) Masters.

Like the rest of the world, not knowing of the global cataclysm that lay ahead, the pair shipped off across the Atlantic in late June 1914. After spending a few days at Edinburgh (their ship's destination), they arrived in London and took up residence in a spare flat in Carlyle Mansions that Alexander's uncle, Henry James, had snagged for his niece, Peggy (Aleck's older sister), who also was travelling with a female companion that summer. Unfortunately, almost from the start of things, Demmler proved himself, according to Henry James, "a dreadful impossibility for any social use whatever." To introduce him among James' circle of acquaintance "would be anguish for Alec & great discomfort for everyone else," he wrote with dismay: "like having the newspaper boy to dine." James' disapproval might also betray other kinds of social anxiety, especially if the young man's behavior and manner threatened to become perilously indiscreet. Earlier that summer, Demmler had came up to Dublin, accompanied by the diminituve Lucien Price, whom he affectionately nickmaned "the thumb". The two of them, hand (Demmler had very large and finely muscled hands) and thumb, proceeded to tell Aleck of a recent trip they had made down to Provincetown "in the hopes of passing an hour or so with out friends who are there "learning to paint."

Whatever reconciliation (or rupture) the two young men may have achieved (or suffered), the outbreak of the European war forced them to abandon their plans for traveling to Munich that August and to head home instead. In Aleck's case, this about-face was matched by another, perhaps more startling, one: arriving back in Cambridge, he abruptly announced his betrothal to Miss Frederika Paine (of Newport, Rhode Island, the daughter of a naval officer), another student whom he had first met at the Museum School. Their marriage was deferred for two years (almost all the other Jameses were fiercely opposed to the union), but Aleck knew that at that moement someone else's feeling also had to be taken into account. "I haven't time to tell you anythingof this morning's happenings," Aleck wrote to his intended, "save that Fred Demmler phoned me that he got in last evening and was leaving today at one. I put off writing you in order to "get to him" as soon as possible and impart a few necessary facts for him to bear in mind."

Aleck and Frederika married in 1916 and spent the summer of their first year of marriage in a tent pitched on the high land that belonged to Abbott Thayer, their eyes, first thing in the morning, last thing at night, on Mount Monadnock, the icon that would guide the rest of their lives. Their had three children: Alexander Robertson "Sandy" James (1918–1995), Daniel James (1922–1955) and Michael "Micky" James (1923–2013). In spite of this bohemian streak, they continued their social calendar, which would always hold a stake in both their hearts, dining with the likes of Henry Cabot Lodge, John Singer Sargent, Isabella Stewart Gardner and Oliver Wendell Holmes. These associations were to serve them well, in spite of Alec’s lifelong ambivalence.

In 1918 they moved to California, where their first son was born, but then moved back East. It is known that Thayer encouraged them to come home and so, sometime around 1919, Alec and Frederika and their infant son packed up and returned. After they arrived, they traveled to Dublin to see Thayer. Dublin, they agreed, was a place that they held in their hearts and they wished to live there. On their way back to Cambridge, Alec and Freddie stopped to buy gas. At that time, there was a station at the bottom of the hill, near the bend in the main road. They looked across the street at a formidable brick house, tucked in by big maples trees. The place had the feel of an English manor, a bit of Cambridge, a bit of old New England. “Oh, what a lovely house,” they said to each other. A little lady was sitting in a chair in the front yard. Alec and Freddie walked across the street and asked if she would consider selling and, soon enough, the house, which had been built in 1826, was theirs. In spite of many leavings, this house would remain the anchor of their lives together. A second son, Danny, was born two years later. Micky, who was born there three years later, recently recalled: “I loved that place growing up. But it wasn’t easy living. The water came from a cistern, I can still hear the way it dripped and there were many things that needed fixing, but they lived there until they died. It was a wonderful place.”

There were no gardens there so Alec and Freddie (as she was known to all) designed elaborate gardens around the house and added mortared stone walls with fashionable brick corners to provide privacy and to give the gardens a European look and feel. They added a garden house, made of brick, like something out of Beatrix Potter. Alec set up his painting studio in a small building behind the house. The light was poor but he carried on in that small space, painting portraits, mostly on commission. For a while, he and Richard Meryman operated a school together and portrait commissions came through the wealthy summer residents who loved the peace and the beauty of the lake and of the mountain. Then came the Depression. Both Alec and Frederika were used to having servants and hired folks to tend to things for them. Scaling down was not a pleasant thought. These new economic constrictions required creative thinking. They discovered that they could rent their house in Dublin to a family from New York and, with that money, they removed themselves to France where life was much cheaper and they were able to carry on in the manner to which they were accustomed. “The Dublin house,” reports Micky, “became the cash cow. They rented it out to rich folks from New York and went to Europe, which seems contradictory but it was much cheaper there.”

And off they went, in 1929, finding a place to rent in St. Jean de Luz, a fishing port in the southwest corner of France known for its architecture, sandy bay and the unusual quality of the light. Alec and Freddie were shown many places that were for rent but they chose one that had been the home of the Duke of Wellington, the noted military officer and statesman of the nineteenth century. They settled in amidst the carved golden mirrors and an infestation of fleas, for which, they soon discovered, the house was famous. Their neighbors were sardine fishermen and daily excursions to the beach for the boys were routine. They were able to find good help, not only to take care of the boys but also to tend to household needs. At one point, Alec and Freddie traveled together to Madrid where they attended bullfights and visited the Prado Museum where Alec absorbed the work of El Greco and Goya, which, according to Micky, was a life-changing experience for him.

But, after the summer spent in St. Jean, Alec once again grew restless. He felt he needed models for his work and a move to Paris was planned. They pulled up stakes and found a suitable spot, not in Paris but in the suburb of Ville d’Avrey, a place, Frederika noted in her journal, where Corot had painted landscapes. There, also, was a school for boys and penny boats that crossed the Seine to Paris, where Alec found himself a studio for the right rent: nothing. Frederika described the house in Ville d’Avrey as “plain, grey, plastered,” but near an orchard and there were gardens and a raspberry patch in the back yard. But the heating system was faulty and they warmed themselves in front of smokey hearthfires, wrapped in coats and scarves, using as well the liquid fire of the French cognac.

The James family returned home to Dublin in October of 1930, or so it seems from Frederika’s journal which is dated only sporadically. According to Barry Faulkner’s notes that accompanied James’ posthumous show (displayed in 1947 and 1948, first at the Currier Gallery in Manchester, NH, then to Boston’s Museum of Fine Art, and finally at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington D.C.), Alec gave up portrait commissions altogether at this time, “burning his bridges” and going “out into the desert.” In fact, he had challenged his friend Richard Meryman with the charge that those who painted these portraits were “whores.” And the desert, it turned out, was a dilapidated center chimney Cape in the woods of Richmond, New Hampshire. This, for Alexander James, was the transformative place, not only for his art but also for his spirit.

A mere twenty-three miles from Dublin, the even smaller town of Richmond was full of rugged characters with wonderful, expressive faces that inspired Alec. Hard-working farmers and loggers made up most of Richmond’s tiny population. In the area of the town known as the Polecat district, Alec found a 113-acre farm. For the sum of $750 – a small fortune in that time of the Depression – he bought from Ozro Bolles the farm and its 1783 house and, for an extra dollar, the contents of the house – the furniture, dishes, tools and all household items. And he set up housekeeping.

To Richmond he took with him the family’s beloved handyman Tony Betz, a skilled carpenter from Peterborough. John Delaney, a mason from Peterborough, came also, to help build a new chimney. It was either Tony or Alec who called the Richmond house “the sweetest place on earth,” Micky can no longer recall which one said it, but it was often said, a benediction that has stuck with the memories of the old house. Tony and Alec swept off the top of the old barn foundation and there built a new studio for Alec, a rough but comfortable place where he worked happily for many years.

In addition, neighbors Franklin and Ethel Morse, Lorie Howard and friend Gerry Whitcomb helped him rebuild the old farmhouse, laying new sills and setting the building back to rights, rejuvenating the inside as well and warming the kitchen table with their yarns. While they worked, Alec not only worked alongside them but he photographed them, especially Lorie Howard, who lived next door. Lorie was a grizzled fellow with an untrimmed beard and tattered clothes, but his eyes were sharp and intuitive. A carpenter’s pencil always stuck up under the brim of his hat, Lorie was the perfect study for the kind of portraits Alec wanted to create, no longer portraits of the wealthy elite but rather portraits of the common man, the workers, their labors evident in their faces and in their hands. In them, Alec found new beauty. Lorie was not only a fascinating study but he was also a good friend to Alec.

Alec’s friend and fellow artist, Barry Faulkner, wrote about these neighbor subjects of Alec’s: “Stepping into the Richmond house you might find the ‘Embattled Farmer,’ who was a selectman of Richmond, stripped to his long winter underwear, doing the town accounts in the warm kitchen. Several of James’s most striking pictures were painted from this friend whose keen intelligence and innate histrionic talent enabled him to produce the revelation of character for which he sought. . . Henceforth, James’s method of painting varied to match the idiosyncracies of his sitter. Sometimes he painted with a passionate directness that was startling in its intensity, at others with a subtlety and wealth of information reminiscent of his uncle’s best prose-portraits.”

These portraits were the justification for Alec’s time in Richmond. In 1937, James had his first New York show at the Walker Galleries, which was successful enough so that three years later, another show was mounted at the same venue.

Towards the end of his life Alexander James was back living in Dublin with his family; he died from heart failure in 1946 and is buried in the local cemetery.

My published books: