Queer Places:

Princeton University (Ivy League), 110 West College, Princeton, NJ 08544

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

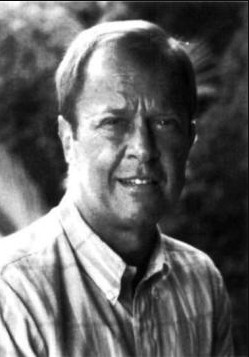

Walter Clemons

(November 14, 1929 - July 6, 1994) was a book critic and writer who was on the staff of Newsweek in the 1970's and 80's.

Walter Clemons

(November 14, 1929 - July 6, 1994) was a book critic and writer who was on the staff of Newsweek in the 1970's and 80's.

Clemons was with Newsweek from 1971-82 and from 1983-88. In those years, he was an editor, a book critic and a senior writer; he also occasionally wrote criticism of ballet. He wrote a number of cover stories, most of them about authors, including Joyce Carol Oates, Saul Bellow and John Cheever. After 1988, he continued to write reviews for the magazine from time to time. He also wrote criticism for The New York Times, where he was an editor of The Book Review from 1968-71, and for other publications. "His gift as a critic was that he had an enormous and easy access to the tradition of literature, and he could call on it without pedantry and without strain," the author Mary Gordon said of Clemons. "And he could attach his great sensitivity and appreciation for contemporary literature to this sense of the past that was very lively."

Clemons was born in Houston, graduated from high school there. He received an A.B. with highest honors in English from Princeton in 1951 and a master's degree with first-class honors in English in 1953 from Oxford, where he was a Rhodes Scholar. After Oxford, he went to work as a seaman in the Gulf of Mexico, in offshore seismic exploration. He also worked as a nightclub pianist in New York City and Rome, where he went in 1960 as a recipient of a Prix de Rome. Clemons was a freelance writer from 1955-65 and was the author of a book of short stories, "The Poison Tree and Other Stories," that came out in 1959. He was an editor with McGraw-Hill in New York from 1966-68, and an editor and writer with Vanity Fair magazine in 1982 and 1983. Late in his career, Clemons worked on a biography of Gore Vidal, but friends said that the book was not finished.

Walter Clemons was a brilliant young writer in 1959, full of promise. That year he published a collection of short stories called The Poison Tree. Mostly drawn from his Texas childhood, they were written in a spare and elegant style. When they brought him the Prix de Rome, he had established himself as a writer to be reckoned with. Clemons had grown up in Houston, the son of a father who was "sort of a village atheist" and a mother who was a "strict puritan" and a Methodist but who never went to church after she was married. Clemons's early experiences with Catholicism, and his subsequent uprising against it, are typical of the way many rebels embrace, and then replace, early ecstatic experiences. There is a certain kind of iconoclast in whom Catholicism invariably induces a ferocious atheism after an initial period of piety. Clemons was that kind of Catholic. To placate his paternal grandmother, young Walter was sent to a Catholic elementary school, and his grandmother picked him up every Sunday to take him to Mass. But his parents never went with him. "They were lolling around the house reading the Sunday Times. I had to uphold the religious honor of the family." Clemons's churchgoing created an immediate crisis: "About the first thing you're taught is that if you don't go to Mass on Sunday, you go to hell," Clemons remembered. "I was under the belief that I was going to go to heaven and I was going to be orphaned while my parents burned in hell. So I used to sob in school. I went through the third grade, and the oppression got worse and worse, and I was taken to a Catholic child psychologist who couldn't get my secret out of me-about hell. He was a good Irish Catholic, Dr. Joe Malloy. He said, `I don't know. Something is scaring the hell out of that little kid in the Catholic school, I think you ought to take him out of the parochial school and let him go to public school.' "I went through various religious stages. I was very devout in early elementary school, and I became very, very devout in adolescence. I can time it exactly because I can remember the embarrassment of being in Mass on Sunday where you kneel down and stand up and kneel down. It was at that age when you never know when you're going to get a hard-on, and you just don't know what to do about it. I think I was afflicted by some sort of religious grief that has to do with a hard-on, of being in a Catholic Mass and being deeply depressed by the music, and getting teary. So I was very religious during my initial erection stage, when I was ten or eleven. It was very much connected with sexuality. Of course, if I become very devout at the moment I'm having erections in Mass, there will be some guilt. "I remember that as soon as I became active sexually I totally lost interest in Catholicism because I found that I could not go to confession and say I was sorry. I became a hardened sinner." He also became an atheist. "I think the religiosity was a substitute for sex. It's a fervent emotional experience, and then I didn't need that anymore." In high school, Clemons read Freud. He had the classic experience of young gay people all over America from the fifties through the eighties. "I read that it was an immature phase in sexual development, so I thought if I could just hang on, the grown-up stuff would start. I knew it was a bad thing. "My picture was in the Houston paper because I won some kind of an essay contest when I was in high school and I got an anonymous telephone call from a guy who'd seen my picture in the paper and had read about the award. We chatted for a while, and then he asked, 'Are you gay?' I don't even think I was aware of the term gay until some years after that. He must have thought that since I was an essay writer, I must have been an incipient fag. I sensed what he was talking about, but I said, 'I don't know what that is.' But I did know. I told people at school that I'd had this peculiar phone call, and that he said, 'Are you gay?' I told them I didn't know what to say, so I said, 'Oh yeah, I have a good time.' And made a schoolyard anecdote out of it. I should have kept my mouth shut." Until he read James M. Cain's Serenade as a teenager, Clemons encountered nothing gay in the culture, although he was aware that he was attracted to male movie stars, like Dana Andrews and Errol Flynn. "I had also a very vivid childhood nightmare that I blush to even remember. It was a dream about nighttime at a deserted circus ring, and there's a group of elephants, one of whom filled his trunk with water and stuck it in my behind. If that's not a sexual dream, I don't know." A student two classes ahead of him at Lamar High School was thrown out after the rumor went around that he'd been caught doing something in the shower. "He went and finished at San Jacinto High and then came back to receive his diploma at Lamar. He walked out on the stage and was met with thunderous applause - a generous ovation. It was very brave of him to come back, and everyone was sorry it had ever happened. This was in June 1945. "I remember when I first got laid [with a girl], at sixteen, and somehow the word got around. I remember a football player friend of mine with whom I worked as a lifeguard said something to the effect of, 'Gee, I've always been kind of shy around you because I never knew you would do anything like that. I feel a lot more comfortable with you now.' And I was crazy about him. I just thought, Well, how sweet. I've made the grade! I'm with the guys now."

Clemons got his first short story published in Scholastic magazine while he was still in high school. He chose to go on to Princeton "because of Scott Fitzgerald and Edmund Wilson and wanting to write songs for the Triangle Show." His dream came true: "I was the musical director of the Triangle Show." He was a tall, blond, good-looking Texan, but he went through college without ever having sex with a man. Then he won a Rhodes Scholarship, and he didn't have sex at Magdalen College in Oxford, either. "There was all sorts of activity at Magdalen. Sort of everywhere but nowhere. I don't know if anybody was actually doing anything, but there was a lot of affection and flirting and all that. I was in no position to know if anybody was getting it on. But surely they were. I would have been so racked with guilt if I'd done anything, and I'm sure they were doing it all without worrying about it. I'm sure many of those people went through what I had read about: they did it and then it was a passing phase. They went on and got married. I have often thought that if I had had a passage of homosexual activity in my teens I might have been much more comfortbale. Who knows?" The Korean Was was on and, after Oxford, Clemons would have been vulnerable to the draft. But during his final six months abroad he was diagnosed with diabetes. He took a job as an ordinary seaman on a boat in the Gulf of Mexico which was surveying the gulf's bottom for oil-well drilling. "I had some very close friends among those men, and a particular friendship with one of the most wonderful guys I ever knew, perfectly straight, very affectionate and physical. His name was L.D. Harris. “L.D. was my age. He was draped around me at all times, and, to my horror, one of the older guys said, `There are two guys that ought to just fuck each other and get it over with!’ “I just froze. And my friend hugged me, and said to this guy, ‘Oh, toilet—mouth, you'd say anything!’ He didn’t have the slightest worry about it. That was really one of the happiest moments of my life.” L,D. was a particular kind of male heterosexual cherished by gay men everywhere: someone so confident of his orientation that he never feels threatened by the homosexuality of anyone else. "He was, therefore, very affectionate with me," said Clemons. "He was a terrific fellow. He was tirelessly heterosexual and a very cute country boy.” Most of the crew on Clemons’s boat came from one little Texas town north of Dallas called Quenlin, The total population was six hundred. “They would fix me up with girls, and I would fuck one of the local girls and I was one of the gang,” he said. Finally, on a trip home to Houston, Clemons had his first gay sexual experience. “I was doing some work in the public library, and there was a men’s room at the bottom of the public library where I discovered that guys were exhibiting themselves and tempting the passersby, and I simply went down there and picked somebody up and went back with him to his room at the Y, where I fucked him and he fucked me. And I said that I had never done this before, and he didn’t believe me. I said, ‘No, I’m telling the truth. I’ve just imagined it.’ And he said, `Well, you’ve got same imaginationI’ He was a very nice man and I never saw him again, although I often think of him as some sort of lucky first encounter. "After this first experience, I went over to my girlfriend’s house, just dazed. But my thought was, I’ve done this once and if you don’t do it again it will just be an experiment”—another typical reaction to an initial encounter. “I abstained for a solid year after that. I continued with this girl, with whom I became impotent with guilt. I think I was so full of conflict that the relationship began to fall to pieces, And then I didn’t want to fuck her anymore. “It was no longer possible for me to continue the fantasy that I would outgrow this. It didn’t seem possible for me to continue a relationship with a woman with whom I would probably be unfaithful. And so I gradually just withdrew from it.”

After a year at sea, Clemons had accumulated enough money to go to Europe, so he lived in London and Paris for a couple of years before moving to New York in 1958. In London, he was cruised on the streets of Chelsea. He began to think “that queers had funny eyes, I was afraid that I would get to look like that. And I only gradually worked out what it was. It’s the cautious homosexuals that looked at you without moving their face. In order not to be caught looking, you’re suddenly aware that you’re being looked at by a face that’s frankly not looking at you at all. So the eyes look very peculiar. It’s a kind of snake-eyed look." His short stories were published in Harpefs Bazaar and Ludies’ Home laurnal, among other periodicals. There was nothing gay about any of Clemons’s fiction, and many of his straight friends were unaware of his orientation. He was an elegant man, with the understated air of a patrician from Texas. He had great confidence in his own intelligence, but he was never boastful, After he moved to New York in the sixties, he escorted many of the city’s most elegant women. He did have one long-term relationship with a man he adored, but many of his closest friends never met his companion; like so many members of his generation, Clemons would always lead a compartmentalized life. But while he remained very discreet, by the time he was thirty, all of his inhibitions about having sex with men had disappeared. For more than thirty years after World War II, beginning with the widespread availability of penicillin and other antibiotics, sexually active Americans enjoyed a kind of liberty that was without precedent in modern times: an almost total freedom from fear of sexually transmitted diseases. For the first time in many centuries, syphilis and gonorrhea became inconveniences instead of catastrophes. Eventually, medical advances would contribute to a dramatic change in the way Americans of all persuasions thought about sex. But because of the sexual taboos of the fifties, many heterosexual New Yorkers had to wait for the arrival of the Pill—and a whole new set of sixties attitudes—before their sexual revolution began. Gay New Yorkers did not have to wait. “It was vividly exciting to sneak around and be in a black tie at a party and make connection with somebody’s eye across the room and meet later after we dumped our dates," said Clemons. And although the scene was much more furtive than it would be two decades later, on any given night in the fifties it could be just as wild as it would be seven nights a week in the seventies.

Clemons was never concerned about catching anything. “Nobody worried about it a bit. You never had a tremor: if you saw somebody you wanted, you went for it. I went to the baths. I went to the Everhard. It cost something like six dollars. I always went at night, and I often stayed all night. “If you got a locker, you put your clothes in the locker. If you took a cubicle, you hung your clothes up in your cubicle. Then you had a little knee-length white gown to wrap yourself in, which you usually wore loose with your cock hanging out. The stomach-downs wanted to be fucked. I guess you could have sex with as many as a dozen people. There were group scenes. There was a very impressive steam-bath room down in the lower level, as well as a swimming pool and a big sort of cathedral-like sauna room. It was very steamy and you could hardly see. You could stumble into multiple combinations.” Once he picked up a man at the baths who was “just hot as a firecracker but clearly under pressure, I went off to the bathroom and came back to the cubicle and he had dressed and vanished, I was quite hurt. Then I saw his picture in the paper the next day.” He had been arrested for hit—and-run driving.

Clemons also went to a bathhouse on West 58th Street near Columbus Circle. “Once in the afternoon, Truman Capote entered and I quickly left. I didn`t know Truman Capote, but I didn`t want to be in the same baths with him. Rudolf Nureyev used to hang out there, and so did Lincoln Kirstein, but I never saw either of them. But the word was around, There was a rather friendly guy at the front desk who I was sort of chatty with, and he would say, `You don’t have any luck, Nureyev was here last night and you missed him again. The best legs I’ve ever seen!`"

After Clemons’s collection of short stories was published in 1959, he made extra money playing the piano in Manhattan nightclubs like the RSVP, where Mabel Mercer was a regular performer. Downtown on West 9th Street, Clemons frequented a popular gay restaurant called the Lion, where he first heard an unseasoned woman singer from Brooklyn. “It was before I went off to Rome. When her first record came out and we began to hear about her in Rome, somebody brought me the record and I looked at that face and realized it was a much glamorized photo of this awful girl that I had heard in the Lion [in 1960]. She was hostile and terribly nervous. She had no contact with the audience and was hunched over the microphone and made something that was supposed to be patter, but was so convoluted and interior that all you felt was this hostility and terrible resentment from this ugly girl. I remember her singing ‘Cry Me a River.’ It was a very muffled act. It must have been one of her very first appearances because she was so tense, It was memorable not because we saw a great star, but because we saw this awful girl.” Despite the way Clemons remembered her, Barbra Streisand won the amateur talent competition at the Lion four weekends in a row. Streisand was “discovered” three years later by Arthur Laurents, when he directed her in I Cun Get It for You Wholesale on Broadway in 1962, "One day this girl came in [wearing] these bizarre thrift-shop clothes,” Laurents recalled. “She was nineteen. She started to sing, and I thought, My God, I’ve never heard anything like this." But the show’s producer, David Merrick, agreed with Walter Clemons. Merrick kept saying, “She’s so unattractive,” and he tried to get Laurents to fire her “every night of rehearsal and out of town.” But Streisand “knew she was going to be a star right then and there,” said Laurents. “And she made sure you knew.” [...]

During A. M. Rosenthal’s tenure, gay employees were treated just as capriciously as gay issues at The New York Times. After his first collection of short stories was published to general acclaim, Walter Clemons stopped writing fiction. Three decades later, he said he had been concerned that if he continued, he might reveal his sexual orientation. “That’s really why I gave up writing fiction. In explaining things, I thought it would show. It sort of dried me up as a fiction writer because I exhausted my safely writable experiences." Whether that was the real reason for his writing block is probably less important than the fact that Clemons believed it was real. Until the 1980s, most gay writers assumed that public identification as a homosexual could quickly end their careers. “Any writer suspected of being homosexual would be immediately attacked by . . . something like ninety percent of the press,” said Vidal. “And the other ten percent would be very edgy in praise, for fear that the writer might be thought to be sexually degenerate.”

After he had stopped writing fiction, Clemons became an editor at McGraw-Hill in Manhattan. One day in 1968 he received a call from a friend at The New York Times Book Review, offering him an editorship. After he had accepted, but before he had started the new job, Clemons went home to Houston to visit his parents. "My mother was planning to have a party the night before I flew back to New York, and the morning of the party I was up very early with my father. He went into the bedroom and came out sort of white, and said, ‘I think she`s gone' My mother had simply died in her sleep. So after the funeral and all the production, I went back to New York and I had bitten the hell out of my fingernails. I had to go for a physical at the Times, and the doctor looked at my hands and asked if I had been under some sort of nervous strain. I explained that my mother had just died and it was a shock, He asked, `Were you very close to your mother?’ And I said, ‘Not especially.` Then he asked if I had had any homosexual experiences, and I said, ‘Well, yes.' It never occurred to me to lie. Ask me a simple question and I`ll give you a straightforward answer. So he said that I’d better see the psychiatrist. They sent me off to a doctor. I wish I could remember his name because he was absolutely angelic. “He asked me about my homosexual experience and when I came out and this and that. Then he asked if I was promiscuous, and I said, ‘No, I’m not now. But I have been. When I first came to New York I was on the streets and in the bars at every opportunity. But I lead a quieter life now.' At the end of the interview, he said, ‘I’m going to recommend that they hire you because you had several chances to lie and you didn’t. I think you have good values and you’re a good person.’” Clemons was baffled: "Well, what did I do right?” he asked. The doctor replied, “When I asked you if you were promiscuous, you could have easily said, ‘Oh no, never.’ It’s perfectly natural that coming from Texas to New York you would have had sort of a wild first few years here, and you were perfectly frank about that. I like the way you talked to me." Clemons continued, “That`s why I wish I could remember his name. Who could be nicer?”

Clemons`s first years at the Times were pleasant ones. “I was sort of unconscious of homophobia at the Times because I did what I think a lot of sort of polite, button-down homosexuals did in those days: I thought I was invisible.” At the Times, Clemons “didn’t really think so much about whether people were thinking about me because I thought, Nobody can see me.” But he turned out to be mistaken. Two years after he arrived on West 43d Street, Clemons was asked to apply for the prestigious position of daily book reviewer. He was widely regarded as the most qualified candidate for the job, but it went to Anatole Broyard instead. Clemons was horrified when he learned from his colleague, John Leonard, that top editors at the paper had launched an investigation of Clemons’s sexual orientation during his tryout. And Clemons was furious when he learned that three of his colleagues—including Christopher Lehmann—Haupt, already a daily book critic—had told his bosses that he was gay, “I was outraged and hurt, and thought, What has this got to do with anything?” Clemons remembered. Shortly after Clemons had been passed over for the job as daily reviewer, Jack Kroll lured him over to Newsweek, where he had a distinguished career as one of the magazine’s senior book critics. “Writing for Walter was definitely a moral act," said Kroll. “He was my favorite among the Times critics. He was too good a man to fall in love with himself. It’s so wonderful to deal with talent and sensibility.” The admiration was entirely mutual: “Jack’s the best editor imaginable," Clemons said. Kroll had no suspicion that Clemons was homosexual. "I always assumed that he and [arts patron] Mimi Kilgore had some sort of thing. I used to think, That lucky fuck, he even got Mimi. I remember a dinner he had with me and a couple of other people at which it soon became clear that he wanted to tell us this. It was very straight and very sweet. The details have been overwhelmed by my failure to spot this—straight guys like to think they can spot this. The word I always used to describe his writing was masculine. And maybe I liked him too much. If you like a guy too much and you’re straight, there’s something that prevents you from making that connection.” Clemons confirmed the identity of one of his accusers at the Times several years later, after another Times editor, Charles Simmons, wrote a novel in which he recounted the incident. When the novel was published, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt telephoned Clemons to arrange a meeting over drinks at the Four Seasons restaurant. “I had never gotten over this even five years later, and I was foolish enough to think they had finally caught on about needing to get rid of Anatole Broyard and they wanted to sound me out about coming back as daily book reviewer,“ Clemons recalled. His fleeting optimism was understandable because nearly everyone in the world of books considered Clemons’s criticism far superior to the work of Broyard or Lehmann—Haupt. Clemons’s failure to become the daily critic at the Times had "made a grievous imprint" on him. "It was the first rejection I had ever had, I had never even asked for a job before. People came to me, and asked, Would you like to do this, would you like to do that? So when I really wanted that job and didn’t get it, I was deeply crushed, So I met Chris and we made chitchat for a while, and he finally said, ‘I’ll tell you the reason I called. I wanted to talk to you about Charlie Simmons's book.' “I hadn’t even seen it. So I said that I wished he had told me because I thought he was looking for someone to review it. But he said, `Let me read you a passage ’: The first person he knew with a hyphenated name, a young attractive bachelor, took him up as a confidant and reported regularly on progress in finding a suitable girlfriend. He was unhappily married at the time and envied the bachelor’s single life until one day the bachelor said, ‘I haven’t had sex in two years, not since I broke up with the dancer friend.’ ‘What happened to her?’ he asked the bachelor. ‘Him,` the bachelor said, and he realized sexual confessions contain propositions. The second man he knew with a hyphenated name, who affected intricate designs with facial hair, who was both boyish and avuncular and who was liked by everyone for a while, prevented a colleague from getting an influential job by telling the employer that the colleague was homosexual. The colleague, over drinks in a bar one evening, said to him, `He didn’t even ask me if I was.` And then after a pause, ‘You know what’s the matter with him? He wants to be a good guy but just can’t.’ “So Chris read me this passage, and I said, `Yes, I did say something like that.’ And he said, ‘Since Charlie has published this, I have always wanted a chance to explain to you, I was too shy to open up the subject and this gives me an opportunity. I have always felt bad about this. You see, the reason I did that was that it’s a very demanding job, and writing reviews can be very personal and under the pressure of the job, I thought that it’“ — Clemons’s homosexuality — “`might come out in your reviews.’ “He thought it was better to prevent this disaster. I thought the explanation was worse than the original events.” Clemons was too stunned to reply, “Yes. I just had a friendly drink with Chris and we went on to other subjects, I went home and told my friend, and he said, ‘What! Weren’t you furious? Didn’t you say anything? And I said, ‘No. I couldn’t think of anything much to say.’ I was seeing a psychiatrist at the time, and I brought this up the following week, and he said, ‘You sat still for that?’ So we had a discussion about not being able to express anger.” Lehmann-Haupt’s recollection of this conversation does not differ markedly from Clemons’s account. Although Lehmann-Haupt denied that his motivation was to prevent Clemons from being hired as his fellow critic, he called Clemons’s description of their drink at the Four Seasons "certainly a way of putting it... I mean that’s the way he saw it,” He also confirmed that after “four, or five, or six hours” of drinking Scotch with Rosenthal in the managing editor’s private office, he told Rosenthal that Clemons was gay. Lehmann-Haupt said he confided to Rosenthal “personally and privately" that he thought Clemons was blocked as a fiction writer “because he doesn’t accept his sexual orientation. “And Abe nodded, and said, ‘Well, that’s very interesting.' And that was, again I say, we took a number of people over similar indiscreet . . .” the critic’s voice trailed off. A quarter century after the event, Lehmann-Haupt admitted that it had been a mistake to confirm to Rosenthal that Clemons was a homosexual. Lehmann—Haupt also agreed that Clemons was “absolutely" a better critic than Anatole Broyard. Rosenthal said he had “absolutely no recollection either that Walter Clemons was gay or that I ever discussed it“ with Lehmann-Haupt. He also denied that he had ever discriminated against any employee because he was gay. Lehmann-Haupt recalled that during their drink at the Four Seasons, “Walter was not giving me an inch. The more I went, the more he sort of looked at me. He wouldn’t even nod. He wouldn’t say, ‘Look, I understand this was tough for you’—or anything that would have given me any kind of relief. And I was stumbling around trying to explain what had happened. I probably didn`t perform very well. I mean, it was certainly one of the most unpleasant experiences I’ve ever been through, and it got worse by the minute."

While Clemons had been working at the Book Review, its editor, Francis Brown, had put him up for membership in the Century Club, a Manhattan institution housed in a Stanford White palace, which counts many of the city’s most accomplished writers and artists among its members. “I had gone to Newsweek in 1971, and at the fall dinner with the new members I ran into Abe Rosenthal—who I had beat in by a couple of years—in his little tux. We found ourselves drinks, and he was very flustered, and said, ‘You’ve gone somewhere, haven’t you?` And I said, ‘Yes, I’m the book reviewer for Newsweek now.’ And he said, `I didn`t mean to say that! I didn’t mean to say that!’ It was the weirdest thing. He was deeply embarrassed and flustered. All I can think is that he was so flustered by running into this fag that he had denied a job to, on the august occasion of his induction, he just lost his head."

Clemons died on July 6, 1994, in his house in Long Island City, Queens. He was 64. The cause was complications from diabetes, said Bernard X. Wolff, a friend, who found Clemons's body.

My published books: