Queer Places:

Limburger Str. 19, 61462 Königstein im Taunus, Germany

Cimitero di Minusio, Via Rinaldo Simen, 6648 Minusio, Switzerland

Stefan

Anton George (12 July 1868 – 4 December 1933) was a German symbolist poet and

a translator of Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, and Charles Baudelaire.

Stefan

Anton George (12 July 1868 – 4 December 1933) was a German symbolist poet and

a translator of Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, and Charles Baudelaire.

George was born in 1868 in Büdesheim (now part of Bitburg-Prüm) in the Grand Duchy of Hesse (now part of Rhineland-Palatinate). His father, also Stefan George, was an inn keeper and wine merchant and his mother Eva (née Schmitt) was a homemaker. His schooling was concluded successfully during 1888, after which he spent time in London and in Paris, where he was among the writers and artists who attended the Tuesday soirées held by the poet Stéphane Mallarmé. His early travels also included Vienna, where during 1891 he met, for the first time, Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

When he travelled to France after graduating in 1889, already thinking of himself as a poet, he met Stéphane Mallarmé, Paul Verlaine and Pierre Louÿs. In Vienna two years later, he had a close encounter with the aspiring poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal, who was only seventeen. Quite what happened between them is unclear, but Hofmannsthal’s father felt he had to write to George, telling him to leave his son alone.

George began to publish poetry during the 1890s, while in his twenties. He initiated and edited a literary magazine named Blätter für die Kunst, and was the main person of the literary and academic group known as the George-Kreis ("George-Circle"), which included some of the major, young writers of the time such as Friedrich Gundolf and Ludwig Klages. In addition to sharing cultural interests, the group promoted mystical and political themes. George knew and befriended the "Bohemian Countess" of Schwabing, Fanny zu Reventlow, who sometimes satirised the group for its melodramatic actions and opinions. George and his writings were identified with the Conservative Revolutionary philosophy. He was a homosexual, yet exhorted his young friends to have a celibate life like his own.[1][2]

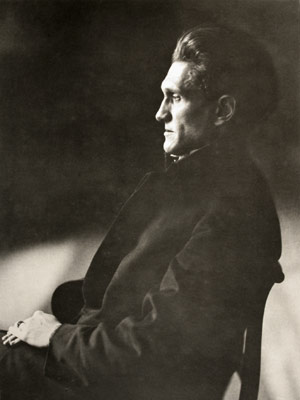

The energy of desire yoked to more spiritual ideals: Stefan George with

Claus and Berthold von Stauffenberg, Berlin, 1924

George had a passionate interest, which he and his subsequent champions always claimed to be entirely spiritual, in teenage boys. (It is beyond doubt that they inspired his poetry.) The most notable of them, because of his ultimate effect on the poetry, was the Bavarian youth Maximilian Kronberger, twenty years George’s junior, whom he met in 1902. ‘Maximin’, as George called him, died of meningitis the day after his sixteenth birthday in 1904. In the poetry that followed, George deified him as an icon of immortal beauty. A year after Maximilian Kronberger’s death, George established a close relationship with an Argentinian boy he had met once before, fourteen-year-old Hugo Zemik (‘Ugolino’). Poems would follow; as would other boys. A pattern had been established.

During 1914, at the start of the World War, George foretold a sad end for Germany, and between then and 1916 wrote the pessimistic poem "Der Krieg" ("The War"). The outcome of the war was the realization of his worst fears. In the 1920s, George despised the culture of Germany, particularly its bourgeois mentality and pre-Vatican II church rites. He wished to create a new, noble German culture, and offered "form", regarded as a mental discipline and a guide to relationships with others, as an ideal while Germany was in a period of social, political, spiritual and artistic decadence.[3] George's poetry was discovered by the small but ascendant Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP), which had its roots in Bavaria. George's concepts of "the thousand year Reich" and "fire of the blood" were adopted by the NSDAP and incorporated into the party's propaganda. George would come to detest their racial theories, especially the notion of the “Nordic superman”.[4] After the assumption of power by the Nazis in 1933, Joseph Goebbels offered him the presidency of a new academy for the arts, which he refused. He also stayed away from celebrations prepared for his 65th birthday in July 1933. Instead he travelled to Switzerland, where he died near Locarno on 4 December 1933. After his death, his body was interred before a delegation from the German government could attend the ceremony.[5]

Among those who had stood vigil at George’s deathbed was the twenty-six-year-old Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg, who had joined the George Kreis at seventeen, along with his brothers. Many years later, on 20 July 1944, Stauffenberg, a lieutenant colonel wounded in action – he had lost one hand, two fingers of the other and the use of one eye – would place a briefcase bomb under the conference table in Hitler’s East Prussian headquarters at Wolfsschanze and leave the room. The briefcase was moved, so that when it went off Hitler was only slightly injured. All of the conspiracy’s leaders were executed.

My published books: