Queer Places:

Yale University (Ivy League), 38 Hillhouse Ave, New Haven, CT 06520

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Princeton University (Ivy League), 110 West College, Princeton, NJ 08544

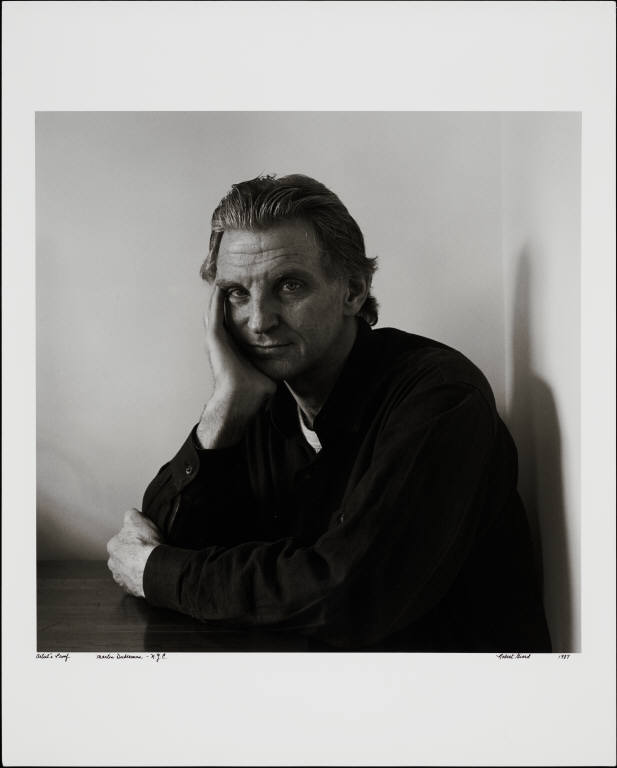

Martin Bauml Duberman

(born August 6, 1930) is an Historian, biographer, essayist, playwright, and

academic. An astute

commentator on gender and race issues and a pioneer in glbtq studies. A member of the pre-Stonewall

generation who recognized the historical significance of the gay movement, his own life arc parallels the

progress gay people have made toward social acceptance.

Born in New York City on August 6, 1930, Duberman grew up in New York, the son of a Jewish garment

manufacturer who had immigrated from the Ukraine and a second-generation American mother. Although

he early evinced interest in theater, his parents discouraged the stage as a potential profession.

A brilliant student, Duberman entered Yale in 1948 and graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1952. He then

undertook graduate studies at Harvard, where he earned a Ph. D. in American history in 1957.

Martin Bauml Duberman

(born August 6, 1930) is an Historian, biographer, essayist, playwright, and

academic. An astute

commentator on gender and race issues and a pioneer in glbtq studies. A member of the pre-Stonewall

generation who recognized the historical significance of the gay movement, his own life arc parallels the

progress gay people have made toward social acceptance.

Born in New York City on August 6, 1930, Duberman grew up in New York, the son of a Jewish garment

manufacturer who had immigrated from the Ukraine and a second-generation American mother. Although

he early evinced interest in theater, his parents discouraged the stage as a potential profession.

A brilliant student, Duberman entered Yale in 1948 and graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1952. He then

undertook graduate studies at Harvard, where he earned a Ph. D. in American history in 1957.

From 1957 to 1961, Duberman taught as an instructor at Yale. His biography of Massachusetts politician Charles Francis Adams (1961), based on his Harvard dissertation, both won the prestigious Bancroft Prize in American history and led to an appointment as Assistant Professor of History at Princeton. Duberman quickly rose through the academic ranks at Princeton, becoming full professor in 1967. He published prolifically on nineteenth-century abolitionists, African-American history, and the growth of radical political movements. He also wrote a series of plays. Duberman's biography James Russell Lowell (1966) was a finalist for the National Book Award. His best known play, In White America (1963), which incorporates text from letters, diaries, and court records to dramatize American race relations, won the Vernon Rice/Drama Desk Award for Best Off-Broadway Production of the 1963 season and was filmed for television in 1970. By 1971, however, Duberman had become weary of the conservative smugness he detested at Princeton. He felt alienated from most of his colleagues there as a result of his sympathy for radical politics and their rejection of his proposals for academic reform. He had been commuting to Princeton from Greenwich Village since 1964, and that also served to distance him from his colleagues, as did his interest in playwriting. To be closer to the heart of the New York theatrical scene, in 1971 Duberman accepted a position at Lehman College, part of the City University of New York, where he was named Distinguished Professor of History. The move from Princeton to a less prestigious university reflected Duberman's growing impatience with academic politics. It also marked an important new beginning in his life.

by Robert Giard

Despite his spectacular success as an academic, Duberman was a very unhappy man in the 1960s. While still an undergraduate at Yale, he had begun to have sex with men, cruising parks, beaches, and bathhouses while maintaining the image of a young heterosexual man. He experienced shame and disgust for his homosexual desires even as he acted on them. Deeply disturbed by his homosexuality, Duberman underwent psychotherapy in order to be "cured." In his 1991 memoir Cures: A Gay Man's Odyssey, he describes the torturous fifteen-year process of attempting to change his sexual orientation, which was not only abysmally unsuccessful but also severely damaging to his self-esteem. His therapists reinforced the societal homophobia that he had already internalized.

Duberman ended therapy in 1970. Thus, his belated acceptance of his orientation coincided with the emergence of the post-Stonewall gay rights movement. He began a cautious exploration of the literature and politics of liberation. This exploration ultimately resulted in an ardent commitment to contesting homophobia in academia and in society at large. In Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community (1972), his acclaimed study of an innovative learning community in North Carolina, Duberman broke the traditional academic boundary of objectivity. Convinced of the need to be forthcoming about his perspective, he came out as a homosexual in his analysis of the homophobic dismissal of the experimental college's theater director. In doing so, he himself became subject to academic homophobia. Duberman quickly became active in the burgeoning gay liberation movement. One of the few prominent out academics at the time, he became a significant media figure, a process accelerated by an essay he wrote on gay literature for The New York Times Magazine in 1972. Duberman served on the boards of the Lambda Legal Defense Fund and the National Gay Task Force and was a co-founder of the Gay Academic Union in 1973. Always critical of elitism and privilege, he clearly saw the connections between gay rights and feminism, and he acknowledged the debt both owed to the African- American civil rights movement. He advocated the inclusion of lesbians in gay movement organizations and attempted to move gay politics beyond the single-issue focus of some of its spokespeople. While embracing gay identity politics he critiqued its failure to subject itself to racial and class analysis.

In addition to scholarly works, Duberman has also authored a dozen plays and a historical novel, Haymarket (2003). Seven of Duberman's plays that explore gender issues are collected in Male Armor (1975). In these pieces he examines the construct of male identity as a skin men use to shield themselves from their own sexual and emotional energies. For example, "Payments" (1971), inspired by the hustler culture that Duberman patronized when he was deeply closeted, explores the psychology of a masculine man who self-identifies as straight while catering sexually to male clients. "Elagabalus" (1973) is a multi-generational portrayal of individuals whose obsessions become a medium through which to enact rituals of power, corruption, and rebellion. Duberman's biography of Paul Robeson (1989), the African-American singer, actor, and civil rights activist, reflects the author's various interests in theater, African-American history, radical politics, and liberation movements.

Duberman founded City University of New York's Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies (CLAGS) in 1991. This program, one of the first such centers at a prominent university, helped make gay and lesbian studies academically respectable, as did his own research and publication in the field, which includes not only scholarly accounts of gay history but also first-person accounts of his own participation in the movement for equality. CLAGS continues as a leader in the gay and lesbian studies movement, sponsoring conferences and awarding research grants, as well as focusing glbtq studies at CUNY. Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past (1989), co-edited with Martha Vicinus and George Chauncey, Jr., one of several anthologies on gay history that Duberman edited or co-edited, presents scholarly essays by a large number of scholars, including Duberman himself, on same-sex sexual relationships throughout history. It is not only a standard reference in the field, but one of the seminal texts that helped define the field of gay history, negotiating a space somewhere between essentialist and social constructionist theories of homosexuality. In About Time: Exploring the Gay Past (1986, 1991), a collection of his own essays, some of which were published in the New York Native, Duberman excerpts and analyzes archival source materials. In these essays, he frequently illustrates how the gay and lesbian past has been obfuscated by policies of libraries and other archives. Stonewall (1994), Duberman's account of a pivotal moment in the gay liberation movement, weaves six personal narratives into a social history of the events leading up to the Stonewall riots, as the homophile movement metamorphosed into the gay liberation movement. The book was the basis for the 1995 film of the same name directed by Nigel Finch, though Duberman has objected to what he considers the film's exaggeration of the role of drag queens in the riots. Midlife Queer: Autobiography of a Decade (1996) is a memoir that takes a topical approach to gay movement politics and scholarship between 1971 and 1981. Left Out: The Politics of Exclusion (1999) compiles Duberman's essays on gender politics, campus radicalism, civil rights, and anti-war activism. Duberman also serves as general editor of two Chelsea House series directed at young people, one consisting of biographies of notable gay men and lesbians and the other focused on Issues in Lesbian and Gay Life. In addition, he is a frequent contributor of reviews and commentary to major periodicals. Informing all of Duberman's work is a grasp of the power of narrative in shaping perceptions of social movements and their relevance to individual lives. Given his personal story of growth from internalized homophobia to gay activism, this emphasis is altogether appropriate.

My published books: