Queer Places:

University of Pennsylvania (Ivy League), 3355 Woodland Walk, Philadelphia, PA 19104

2019 Delancey Pl, Philadelphia, PA 19103

Mortimer's, 1057 Lexington Ave, New York, NY 10021

Glenn Bernbaum (April 5, 1922 - September 7, 1998)

was the owner of Mortimer's restaurant, a favorite watering hole for Manhattan socialites, glitz folk and achievers since 1976.

Glenn Bernbaum (April 5, 1922 - September 7, 1998)

was the owner of Mortimer's restaurant, a favorite watering hole for Manhattan socialites, glitz folk and achievers since 1976.

Robert Glenn Bernbaum was born on April 5, 1922, in Philadelphia to Harry Bernbaum, a prosperous retailer who owned Lousols, a Bergdorf Goodman-like specialty store, and his wife, Elsie, a music and art patron who took great pride in the family’s antique-filled townhouse on Delancey Place, just off Rittenhouse Square. Their lifestyle was about as Main Line as you can get for a Jewish family: The four Bernbaum children – Harry, Jeanne, Robert Glenn (then known as Bobby), and Phyllis – were chauffeured to private schools, given tennis and music lessons (Glenn played the mandolin), and cared for by a staff of seven. Glenn attended Friends Select School and Germantown Academy. “Our parents would go off to Europe quite a bit and leave us with the nurse,” recalled Phyllis Gabaeff, a divorcée who lived in Florida and worked at Barnes & Noble. The family belonged to a temple, but they never celebrated Jewish holidays.

In later years, when he was a well-established figure in New York, Bernbaum rarely spoke of his family. Sam Green, a private art curator who rented an apartment from Bernbaum above Mortimer’s and dined with him weekly, said, “His feeling about his family was, ‘I don’t want those ordinary people in my life; I want extraordinary people.’ ” Bernbaum kept his family life such a secret that the New York Times obituary failed to mention that he was survived by two sisters instead of just one (brother Harry, a clothing buyer based in Georgia, died of prostate cancer a decade ago). Even Bernbaum’s lawyer, Aaron Richard Golub, didn’t initially have the sisters’ names and addresses to track them down for next-of-kin notification. Gabaeff, who had received a check and a note from her brother as recently as August, found out about his death when a friend sent her the Times obituary. Bernbaum had not spoken to his older sister, Jeanne, for 30 years, declining to respond to her recent notes trying to reestablish a relationship.

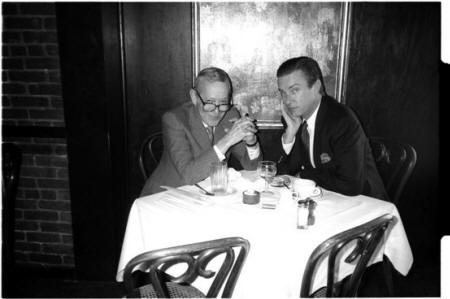

Glenn Bernbaum and Paul Wilmot

Perhaps one of the reasons he kept his distance from family members is that he never felt comfortable acknowledging his homosexuality to them. “He kept it very quiet,” said Gabaeff. Bernbaum attended the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia – both before and after his stint in the Army in World War II – and during his school years, rumors about his sexuality filtered back to his family. His mother was quite distressed and didn’t want the matter discussed, according to a family intimate, and Bernbaum apparently preferred to keep his lifestyle private. When World War II started, he left Penn and entered the Army, serving in the psychological warfare division.

After the war, he returned to Penn, graduating with a degree in political science, and ran the family store briefly after his father died. But Bernbaum argued with his mother, and the store was ultimately sold. He subsequently worked as a buyer at a Philadelphia ladies store, then moved to New York and became the general merchandise manager at the Franklin Simon department store, where he showed some panache. “He had Andy Warhol do silk screens for the store awnings,” recalled Kenneth Lane. “He wasn’t very avant-garde, but he had good taste.” Bernbaum left Franklin Simon after fighting with management and joined – never mind the indignity of being part of such a lowbrow enterprise – the famous discounter E.J. Korvette’s. He didn’t last very long there either.

In 1959, he began running the Custom Shops, a New York chain of men's-wear stores owned by Mortimer Levitt. Bernbaum would travel to London with friends like Bill Blass and Kenneth Lane to pick fabrics. He was soon earning enough to afford a 52nd Street townhouse, beautifully decorated by Albert Hadley. Hadley would later decorate Bernbaum’s apartment over Mortimer’s, a luxurious retreat with a custom-designed sleigh bed, Venetian chairs, and fur throws.

He remained at Custom Shops for 20 years as executive vice president, a position he retained for four years after opening his restaurant. Although it was generally considered that the restaurant was named after Levitt, Bernbaum maintained that the name came about through a combination of circumstances -- in rapid succession, a dinner at Morton's, a restaurant in London; a talk with his friend Stanley Mortimer, a grandson of a founder of the Standard Oil Company, and a visit from Levitt.

Bernbaum built Mortimer's on the sheer force of his personality. An unassuming, brick-walled, moderate-size restaurant at Lexington Avenue and 75th Street, it became virtually a private club to the sort of fashionables whose names fill the gossip columns. Through the years, Bernbaum spent hours each day juggling seating arrangements because his restaurant had only 19 tables, most of which barely accommodated four diners each. Royalty, nobility and status names like Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Brooke Astor, Gloria Vanderbilt, Bill Blass, Reinaldo and Carolina Herrera, and Nan Kempner were automatically assigned visibility -- 1B, the window table to the right of the door. On the rare times when these luminaries were not present, Bernbaum had to make decisions that would stump Solomon. If there was a party of four or five ''known'' people, the table went to them. If there were more than one party of such rank, Bernbaum would reach back to his maxim: ''The trick in seating is not where they are but who they are surrounded by.'' Generally, older well-knowns got tables along the wall and younger ones got the tables down the middle. Diners of faint accomplishment were exiled to tables near the kitchen, Bernbaum's version of Elba. Men and women not familiar to the owner or the maitre d'hotel were known to stand forlornly at the door for embarrassing minutes and were often brusquely turned away. A food critic dining anonymously at Mortimer's once described the welcome accorded walk-ins as a greeting normally given to bill collectors. Bernbaum's decisions naturally inspired strong feelings, as did his favorite stance, hands clasped behind his back. The unrecognized thought him rude, affected and elitist. The ''regulars'' considered him one of their own. Bernbaum, when he deigned to defend himself, observed that all restaurateurs favored friends and loyal customers. Mortimer's was generally acknowledged to be the clubby East Side restaurant described by Tom Wolfe in ''Bonfire of the Vanities.'' But the scenes for the film adaptation were not photographed there, because the movie people ''believed people in the Midwest wouldn't understand the plainness of the place,'' Bernbaum once said. The undistinguished decor of Mortimer's was matched by the food, which rated few critical accolades. But the menu items known as comfort foods -- twinburgers, chicken hash, mashed potatoes, lemon meringue pie and rice pudding -- were renowned among the sophisticated clientele. Renowned, too, were the moderate prices, no small attraction to the well-heeled. ''The rich don't like to spend money,'' Bernbaum said. ''And they like to spend money here less than anyplace else.'' Many of the rich used the restaurant for private parties -- birthdays, anniversaries, farewells and welcomes for social lion guests -- and publishers used it for book parties. Bernbaum orchestrated almost all of them, from the table settings and flowers to the theme decorations. He also created what came to be known as his ''society sandwiches'' for them, little triangles that were consumed like peanuts.

Bernbaum was considered unflappable, perhaps because little could measure up to a flap he survived soon after establishing Mortimer's. Police officers walked in one day and arrested the maitre d'hotel Bernbaum had brought from Greece. The charge: conspiracy to murder Bernbaum. In the drawl that no one could quite define and in a milder than expected reaction, Bernbaum said he was ''surprised.'' It seemed that several employees had been told that they were in the Bernbaum will, and the maitre d'hotel thought he would hurry things along. The man, who had been turned in by a fellow employee, was convicted and spent several years in jail. Bernbaum also originated the annual Fete de Famille, a benefit for the AIDS Care Center at New York Presbyterian Hospital. Started in 1986, the fete, held outdoors on 75th Street, has raised almost $7 million.

When Glenn Bernbaum returned from a European vacation in July 1998, he looked terrible and complained loudly that he didn’t feel well. But he hated seeing doctors and refused to be examined, even as his health deteriorated. So one by one, his rich and famous customers – those charmed lifers who would often spend their nights off from the spangled-gala circuit encamped in Mortimer’s front room – made pilgrimages to plead with him, conspiring with one another to try to get him help. Reinaldo Herrera lunched with Bernbaum and was frightened by his appearance. “I told him, ‘Glenn, your eyes are yellow, it could be jaundice, you’ve got to see a doctor,’ ” said Herrera, the husband of designer Carolina Herrera and Vanity Fair’s special-projects editor. Bernbaum brushed him off, growling back, “I’m fine, it’s just the light coming through the yellow awning.” Mario Buatta was so upset – “Glenn was the color of a yellow squash” – that he called Bill Blass and Nan Kempner to see if they could talk some sense into Bernbaum. “Glenn was furious at me when he found out,” said Buatta, the decorator known as the Prince of Chintz. “He was going around saying, ‘Mario, that SOB.’ ” Even socialite Nan Kempner was rebuffed. “I tried my damnedest,” she said, detailing her visits and repeated phone calls. “He finally said, ‘Stop bullying me; I’m a big boy.’ “ Bill Blass, who had befriended Bernbaum back in the fifties when they were both young men in the garment industry, offered to bring a limo and accompany him to the doctor, to no avail. “The possibility of being in the hospital, being cared for, was too intimate for him,” Blass said sadly. Uncomfortable with the attention, his energy flagging, Bernbaum eventually retreated to his apartment above the restaurant, taking few phone calls and refusing visitors. Senga Mortimer, the House & Garden editor who was one of Bernbaum’s closest friends, was so concerned that she went to the restaurant, called Glenn, and announced she wasn’t leaving until he appeared. Four long hours later, Bernbaum relented, coming down for comfort and conversation, and the next day he did get in touch with a doctor. But after decades of prodigious alcohol consumption, it was too late for Bernbaum to reverse the damage – weeks or months or perhaps years too late.

Bernbaum died on September 7, 1998, at his home in Manhattan. He was 76. The cause of death was unknown, his lawyer, Aaron Richard Golub, said. Golub said the restaurant would be closed indefinitely and that no decision had been made as to whether it will reopen. He bequeathed the 100-year-old building in which the restaurant was situated, and where he also lived, to Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, making it clear that he wanted his restaurant closed down. The will also states that Bernbaum wanted no memorial service--a desire which has left his friends bemused and unhappy. Many feel the need for closure. Bernbaum, famous for being the perfect partygiver, was not a diplomatic man. Instead, he was often grumpy and crotchety. Art historian John Richardson describes his first meeting with Bernbaum, during which he initially assessed Bernbaum as a "drunken curmudgeon," but later grew to understand him. Bernbaum's personality gave Mortimer's an unstuffy atmosphere. Art dealer Sam Green described the time he brought Greta Garbo to the restaurant. “Why do people love a curmudgeon?” Kenneth Jay Lane, the jewelry designer said, sitting in his office with its sparkling showcases of fabulous fakes, contemplating his four-decade friendship with Glenn Bernbaum. “There has to be one curmudgeon in every crowd. Charming people are a dime a dozen.” “He could be the bitch of all times,” said Nan Kempner, who always thought his behavior stemmed from profound insecurity, the need to put down others to feel good about himself. Mortimer Levitt, the founder of the Custom Shops, where Bernbaum worked for twenty years – and in whose honor, it’s said, the restaurant was named – admitted, “He was absolutely, unquestionably a snob.” Kenny Lane, who traveled with Bernbaum in Spain and Venice the July before his death, said, “he was emulating Scrooge.” Added the diplomatic Senga Mortimer, “To say he was difficult was being kind.”

My published books: