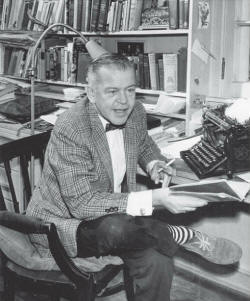

Partner William Chancey

Queer Places:

US-18 & WI-83, Wales, WI 53018

Salem Cemetery

Wales, Waukesha County, Wisconsin, USA

Edward Harris Heth (September 13, 1909 - April 26, 1963) was an University of Wisconsin graduate, advertising man and author of seven novels. Also an expert gardener and cook.

After college at University of Winsconsin, he moved to New York in the 1930s to pursue a career in writing. He moved back to Wisconsin in the 1940s (he seems to have had a breakdown of some sort) and settled in a farmhouse in Wales. With his partner Bill,

they lived in Wales until the 1960s: Bill was a successful ceramist, and Heth

wrote on food and Wisconsin (sort of a Midwestern M.F.K. Fischer).

Edward Harris Heth (September 13, 1909 - April 26, 1963) was an University of Wisconsin graduate, advertising man and author of seven novels. Also an expert gardener and cook.

After college at University of Winsconsin, he moved to New York in the 1930s to pursue a career in writing. He moved back to Wisconsin in the 1940s (he seems to have had a breakdown of some sort) and settled in a farmhouse in Wales. With his partner Bill,

they lived in Wales until the 1960s: Bill was a successful ceramist, and Heth

wrote on food and Wisconsin (sort of a Midwestern M.F.K. Fischer).

Edward Harris Heth was born in Milwaukee, WI, and attended grade and high school there. "I was expelled from high school for reading Theodore Dreisler's 'An American Tragedy.' My English teacher put up a great fight and got me back in. After all. it's a great American novel," Heth argued. "When I was 15 and in high school I produced a review at the art institute," Heth said. Called "Kaleidoscope," the full- fledged musical ran three nights. "I wrote it; I wrote the music; I acted in it; I designed the costumes, and I think I played in the orchestra," Heth recalled laughingly. His high school friends comprised the cast. Following high school. Heth went to the University of Wisconsin.

From an early age, Edward Harris Heth of Milwaukee was on track for literary success. Heth published his first short story as a 19 years old college student. At that time, shortly after completing the story, he had a chance meeting with Zona Gale, whe well-known Wisconsin author. She read Heth's first venture into short story writing. "Could I keep it?" she asked the young University of Winsconsin student. Heth readily assented. Shortly afterward he received a letter from H.L. Mencken, saying he was buying the story for The American Mercury. Heth recalled the first story, called "The Earlier Life." "It was the story of a little girl coming home from boarding school. Her parents had killed her cat. It was her first real tragedy," Heth explained.

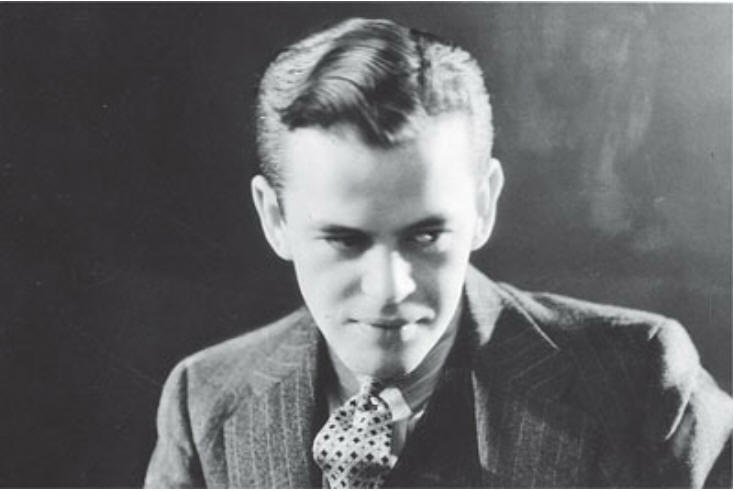

A young Edward Harris Heth. His career as a writer would lead to movie

adaptions of his books. SOME WE LOVED, 1935

A few months later, Mencken purchased Heth's second story. "Hester Garland" told of a lonely city girl who married a small-town boy.

While still a student at the University of Wisconsin, Heth was published in the book Wisconsin Writings—1931: An Anthology. Heth’s 1931 contribution was a story titled “A Party for Ginevra.” The young writer from Wisconsin set his story in decadent Paris, which allowed him to describe intimacies between men that would seem out of place in America.

After graduating from Wisconsin, Heth went off to use his writing skills in an advertising career in New York, though he continued to write fiction, publishing several novels in the late 1930s. After one year he was back to Milwaukee. After his father's death, Heth published his first novel, "Some We Loved," published in 1935.

He became head of a WPA writer's project, working at compiling a guide book to the city. During this time, he wrote his second novel. "Told With a Drum," the story of a German family living in Milwaukee during WWI. "After I left the WPA, I started a flower shop. It's stiil run by my sister," he said. After two veers of arranging flowers for debut parties, Heth again headed for the East. "I just free-lanced in New York, writing short stories," Heth said. His name began to appear in such magazines as Colliers, Good Housekeeping, and the Yale Review. Three of his short stories -- in 1936, 1937, and 1947 -- were destined to be named among the best short stories of the year. Meanwhile, his third book, "Light Over Ruby Street," was published. "I was offered the job of writing 'Mary Marlin.'" he said. "She was a lady senator from Iowa who was the president's right hand woman. She practically ran the country," Heth said of the daytime radio serial.

A 1945 novel about boyhood in Milwaukee and the protagonist’s gambling father, Any Number Can Play, was a critical success. In 1949 it proved a financial success as well when it was made into a movie starring Clark Gable and Alexis Smith. In those prudish times, the movie poster advertising “MGM’s Virile Romantic Drama” also bore the notice, “Not Suitable for Children.” Heth wrote his fourth novel, "Any Number Can Play," in six weeks time, while he was in New York City. Even before the book came out, the movie rights to it had been sold. The successful novel was published in Portuguese, Spanish, Danish, Swedish and French.

Heth returned to Wisconsin after World War II.

Heth lived with his partner in the Welsh Hills of Waukesha County. The medicalization of homosexuality to which Kinsey contributed would frame the later life of Edward Harris Heth.

In My Life on Earth, a semiautobiographical work published in 1953, Heth wrote nostalgically about his “full breathless New York years.” But the city had taken its toll, and he was suffering from nerves, high blood pressure, and hypertension. The doctor he consulted, noting that Heth worked in advertising, called him a “Madman.” He then told his patient, “Six months out of the city, some place quiet in the country, and you’ll be yourself again.” Heth chose not to seek the solace of the Connecticut countryside, as many New Yorkers did, but went back to rural Waukesha County, Wisconsin, where his grandparents had once farmed. After some time in the country, Heth explored the possibility of going back to New York in advertising, but because he would have received only half his previous salary, he decided against it.

While recuperating in Wisconsin, he wrote as the narrator of My Life on Earth, “For a year I had tried to keep neighbors from bothering me. Until, in the second spring Bud Devere dropped by. He was young and burly, and grinned when I opened the door.” Devere invited Heth’s narrator to church supper that night. But, the narrator recalled, the “next evening, I started out again to travel alone over the long silent roads.” He left the house to avoid Devere, who said he might drop by the next evening. But avoidance was not going to work. “Bud Devere,” Heth’s narrator continues, “that second spring, persisted in being a friend. . . . He came up for evening sessions of talk—uninvited, mostly, which did not bother him, and often unwelcome, which also did not seem to trouble him.” The scene concludes with the narrator explaining: “Bud had reached over to tap me on the shoulder. ‘You’re all right. Nice to have you in the neighborhood.’ ” Here, in the McCarthy era, Heth used My Life on Earth to argue that the cure for the supposed “sickness” of homosexuality was not psychiatric treatment, but rather two males finding friendship and love.

Heth’s narrator also remembered when the contractor who built his house in the Welsh Hills asked, “Why did I need a kitchen the size of an old farmhouse kitchen, with a fireplace in it? Good humoredly, but with an admixture of wonder, he kept asking what a wife (I didn’t have one, I reminded him. ‘Ought to,’ he answered.) would say to a kitchen where you had to walk a mile each day, traveling from the cupboards to the stove and back again.” The narrator recalled other neighbors also “said I must be going to get married or why’d I have a sink and stove and so many cupboards and everything put in.”

My Life on Earth is most often referred to as semiautobiographical. Edward Harris Heth did build a house in the Welsh Hills, but he lived in it with his male partner, a well-known ceramist named William Chancey. They had met in New York City. The neighbors, including Heth’s electrical contractor, generally knew the two were gay and seemed to accept them. Since this was the 1950s, a time of witch hunts against radicals and gays, Heth could not write openly about a domesticated gay couple in the country, so he wrote a late-appearing fiancée into the last part of his book for the narrator to marry. This plot echoes that of Heth’s 1931 story about a phantom marriage that never took place.

Friendly canine members of the household were Smith and Timm. Smith, a collie and "a very fine show dog," and the half cocker, half water spaniel son of Shag and Ida, of whom Heth often wrote, romped through the gardens and were loved impartially. Although the Wales hilltop was bare when Heth bought it, after the house was built, the one-story frame building was surrounded by gardens filled with flowers of every color and description. A picture window in the living room offered a sweeping view of a tree-bordered meadow. Five terraces lined the hillside, one offered a peaceful view of the evening sunset. From the foot of the hill a fast-moving train roared its passing greeting.

In Heth’s 1951 Almanac: A Handbook of Pleasure, he acknowledged that “Mr. Chancey shares the House on the Hill.” The small, self-published twenty-six-page document was basically a monthly calendar stuffed with local rural lore. The unusual feature was artwork from, as Heth put it, “Wisconsin’s noted young art group,” including a picture of a pottery piece by Chancey. Several of the artists would later appear in other gay social circles.

In 1952 he adapted his second novel "If You Lived Here" for a New York musical comedy. He obtained the option for the musical when Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, who lived about three miles away, introduced Heth to the producer of the comedy. The story is about a school teacher and has been compared to the highly successful Thornton Wilder opus "Out Town." In addition to writing the novel, he wrote the lyrics to songs for the show. "It's the story of a Wisconsin teacher in a small Wisconsin town, a combination of Wales and Genesee Depot," Heth explained. Her pupils return to help celebrate her 50th anniversary as a teacher, and questions run through her mind: "What has she taught them?" "Was she a failure?"

His final publication in 1956 was The Wonderful World of Cooking.

In his later years, Heth, though still creating literary works, was known more for his folksy country cooking. Naturalist Euell Gibbons wrote an introduction for the second edition of his cookbook. Heth also had a show on Wisconsin Public Radio telling tales of the Wisconsin countryside. The home where he lived with Chancey, known as the House on the Hill, burned down in 1960 while the two were out of town. Though the house was rebuilt, Chancey committed suicide in 1961, and Heth sold the home they had shared. He moved into an apartment in Milwaukee and died on April 26, 1963. Heth seems to have taken his own life after Bill died.

My published books: