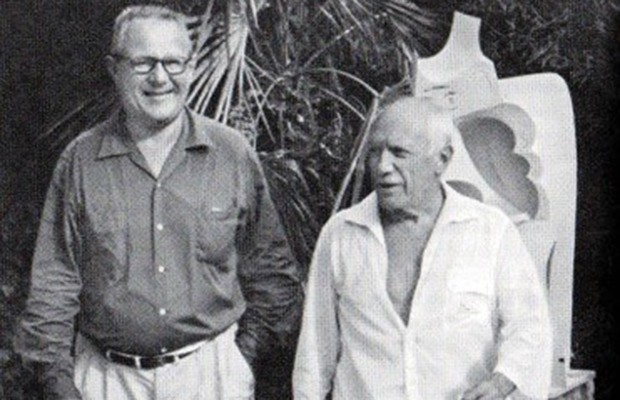

Partner Basil Mackenzie, 2nd Baron Amulree, John Richardson

Queer Places:

Repton School, Willington Rd, Repton, Derby DE65 6FH, UK

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

Sorbonne, Sorbona, Parigi, Francia

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

Bryn Mawr College (Seven Sisters), 101 N Merion Ave, Bryn Mawr, PA 19010

Château de Castille, Chemin du Château, 30210 Argilliers, Francia

Arthur William Douglas Cooper, who also published as Douglas

Lord[1][2] (20 February 1911 – 1 April 1984)[3] was a British art historian, art

critic and art collector. He mainly collected Cubist

works. According to James Lord, around 1948

Basil Mackenzie, 2nd Baron Amulree was having an

affair with the art historian Douglas Cooper; when they parted, Cooper

settled with John Richardson.

Arthur William Douglas Cooper, who also published as Douglas

Lord[1][2] (20 February 1911 – 1 April 1984)[3] was a British art historian, art

critic and art collector. He mainly collected Cubist

works. According to James Lord, around 1948

Basil Mackenzie, 2nd Baron Amulree was having an

affair with the art historian Douglas Cooper; when they parted, Cooper

settled with John Richardson.

Early in the 19th century, Cooper's

forebears had emigrated to Australia and acquired great wealth, in

particular property in Sydney. His great-grandfather Daniel Cooper became a member of the New South

Wales legislature and was the first Speaker of the new Legislative Assembly in 1856. He was made a

baronet in 1863 and spent his time both in Australia and England,

eventually settling permanently in England, and dying in London. His son

and grandson also lived there and sold their Australian property in the

1920s, very much to Douglas's annoyance.

Douglas's mother came

from old-established English aristocracy. His biographer and longtime

partner John Richardson considered

his suffering from the social exclusion of his family by his countrymen

to be a defining characteristic of his friend,clarify explaining in

particular his Anglophobia.[4][5] Cooper never

visited Australia and proposed that he might have been conceived there

during the honeymoon of his parents.[6]

As a

teenager, his erudite uncle Gerald Cooper took him on a trip to Monte

Carlo, where Cooper saw the Sergei Diaghilev's ballet company; his

biographer traces an arc from here to Cooper's late work ''Picasso et le

Théatre''. He went to Repton School and Trinity College,

Cambridge, graduating in 1930 with a third in the French section and a

second (division 2) in the French section of the Medieval and Modern

Languages Tripos. When he was 21, he inherited £100,000, enabling him to study art history at

the Sorbonne, in Paris and at the University of Freiburg in Germany,

which was not possible at the time in Cambridge.

In

1933, he became a partner in the ''Mayor Gallery'' in London and planned

to show works of Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger,

Joan Miró and Paul Klee in collaboration with

Paris-based art dealers like Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and Pierre

Loeb (1897–1964); however, this collaboration ended fast and

unfavourably. Cooper was paid out in works of art.

Cooper attributed

this failure not least to the conservative policy of the Tate

Gallery; according to Richardson, his resentment was the catalyst for

the structure of his own collection, which should prove the backwardness

of the Tate Gallery. At the outbreak of the Second World War 1939, he

had acquired 137 cubist works, partly with the help of collector and

dealer Dr. Gottlieb Reber (1880–1959), some of them masterpieces, using a third of his

inheritance.[7]

Cooper was not eligible for

regular military service, due to an eye injury, so he chose to join a

medical unit in Paris when World War II started, commanded by

the art patron Etienne de Beaumont, who had commissioned works by

Picasso and Georges Braque, among others. His account of the

transfer of wounded soldiers to Bordeaux to be shipped to

Plymouth achieved some fame when published in 1941 by him and his

co-driver C. Denis Freeman (''The Road to Bordeaux''). For this action,

he received a French ''Médaille militaire''.

Back in

Liverpool Cooper was arrested as a spy because of his French

uniform, missing papers and improper behaviour, a treatment for which he

never forgave his fellow countrymen. Subsequently, he joined the Royal

Air Force Intelligence unit and was sent to Cairo as an interrogator,

a job at which he was enormously successful in squeezing out secrets

from even hard-boiled prisoners, not least due to his “‘evil queen’

ferocity, penetrating intelligence, and refusal to take no for an

answer, as well as his ability to storm, rant, and browbeat in

Hochdeutsch, dialect, or argot, which were

just the qualifications that his new job required.”. He enjoyed the

social life there greatly.

After a short

interlude in Malta, he was assigned to a unit trying to investigate

into Nazi looted art: ''Royal Air Force Intelligence, British Element,

Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives'' (MFAA).[8] He was very successful, his most eminent discovery

being the ''Schenker Papers'' which made it possible to prove that Paris

dealers, Swiss collectors, German experts and museums, in particular the

Museum Folkwang in Essen were deeply engaged in looting Jewish

property and ''entartete Kunst'' as well as building collections for

Hitler and Hermann Göring (Schenker was the

transport company shipping art to Germany, having excellent

bookkeeping).[9]

Equally

amazing to MFAA investigators was his detailed

research on the Swiss art trade during the war; it turned out that many

dealers and collectors had been involved in trading looted art. Cooper

spent the whole month of February 1945 as emissary of the MFAA and the

correspondent organization of the French, interrogating dealers and

collectors having dealt with the Nazis and especially Theodor Fischer of the Fischer Gallery who in 1939

managed the sale of confiscated "degenerate"

artworks.

He was particularly proud to have

found and arrested the Swiss Charles Montag, one of Hitler's

art advisors, who had assembled a private art collection of mostly

stolen items for the Führer and was involved in the liquidation of

the Paris gallery Bernheim-Jeune; surprisingly, Montag was quickly

released. Cooper arrested him again immediately, only to see him set

free once again, due to Montag's good connections to Winston

Churchill, who refused to believe that his longtime friend and teacher

"good old Montag“ could have done anything objectionable.

After the Second World War, Cooper returned to England, but could not

settle in his native country and moved to southern France, where in 1950

he bought the Château de Castille near Avignon, a suitable place to

show his impressive art collection, which he continued to expand with

newer artists like Klee and Miró. During the

following years, art historians, collectors, dealers and artists flocked

to his home which had become something like an epicenter of Cubism, very

much to his pride.

Léger and Picasso were regular guests; the latter even became a

substantial part of its life. He regarded Picasso

as the only genius of the 20th century and he became a substantial

promoter of the artist.[10] Picasso tried

several times to induce Cooper to sell his castle to him; however, he

would not agree and finally in 1958 recommended to Picasso the

acquisition of Château of Vauvenargues.

In 1950, he became acquainted with art historian John Richardson, sharing his life with him for the next 10

years. Richardson moved to Provence in southern France in 1952,

as Cooper acquired Château de Castille in the vicinity of Avignon

and transformed the run-down castle into a private museum of early

Cubism. Cooper had been at home in the Paris art scene before

World War II and had been active in the art business as

well; by building his own

collection, he also met many artists personally and introduced them to

his friends. Richardson and Cooper became close friends of

Picasso,[11] Fernand Léger and Nicolas de Staël as well. At that time

Richardson developed an interest in Picasso's portraits and contemplated

creating a publication; more than 20 years later, these plans expanded

into Richardson's four-part Picasso biography ''A Life of Picasso''.[12] In 1960, Richardson left Cooper and

moved to New York City.

Cooper published frequently

in The Burlington Magazine and wrote numerous monographs and

catalogues about artists of the 19th century, including Edgar

Degas, Vincent van Gogh and Pierre-Auguste

Renoir, but also about the Cubists he collected. He was among

the first art critics to write about modern art with the same

erudition common for artists of the past; in the years before the Second

World War, he was a pioneer in this respect. When his catalogue of the

exhibition ''The Courtauld Collection'' appeared

in 1954, The Times wrote about it: “it is not easy to think

of another critic who has so consistently applied to modern painting the

scholarship normally used in the study of the works of the more distant

past.” THE TIMES: ''Benefactor of Art: Courtauld and His

Collection''.[13]

His most

important achievement is probably the catalogue raisonné of Juan

Gris, which he completed in 1978, six years before his death, and 40

years after beginning it. He was Slade Professor of Fine Art at

Oxford from 1957 to 1958 and guest professor at

Bryn Mawr and Courtauld Institute in 1961.

Towards his life's end, he was honoured by being appointed the first

foreign patron of the Museo del Prado in Madrid, which made him very

proud. In gratitude, he donated his best Gris to the

Prado, ''Portrait of the Artist's Wife'' from 1916, and a cubist ''Still

Life with Pigeons'' by Picasso. His only other donation went to the

Kunstmuseum Basel; the Tate Gallery didn't receive anything. Cooper

died on 1 April 1984 (''Fools' Day''), perhaps completely fitting, as he

predicted. He left an

incomplete catalogue raisonné of Paul Gauguin and his art collection

to his adopted son William McCarty Cooper (having adopted him according

to French law, in order that nobody else would inherit anything, in

particular not his family).[14]

His written legacy is kept at the Getty Research Institute, Los

Angeles, CA.

My published books: