Queer Places:

Villa Ocampo, Elortondo 1837, B1643 Béccar, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Cementerio de la Recoleta

Buenos Aires, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Capital Federal, Argentina

Victoria

Ocampo

CBE (7 April 1890 – 27 January 1979) was an

Argentine writer and intellectual, described by

Jorge Luis Borges as La mujer más argentina ("The

quintessential Argentine woman"). Best known as an advocate for others and

as publisher of the literary magazine

Sur, she was also a writer and critic in her own right and one of

the most prominent South American women of her time. The Second Republic

would usher in a period where women had more rights under the law, and

where women were politically empowered for the first time. Homosexuality

was also stripped from the penal code, though there were still ways for

which lesbians could be charged, for example by being deemed dangerous to

the state, or simply being detained by the state even if their behavior

was not criminal. Prominent lesbians of this period included

Lucía Sánchez

Saornil, América Barroso,

Margarita Xirgu,

Irene Polo,

Carmen de Burgos,

María de Maeztu,

Victoria Kent and

Victoria Ocampo.

Victoria

Ocampo

CBE (7 April 1890 – 27 January 1979) was an

Argentine writer and intellectual, described by

Jorge Luis Borges as La mujer más argentina ("The

quintessential Argentine woman"). Best known as an advocate for others and

as publisher of the literary magazine

Sur, she was also a writer and critic in her own right and one of

the most prominent South American women of her time. The Second Republic

would usher in a period where women had more rights under the law, and

where women were politically empowered for the first time. Homosexuality

was also stripped from the penal code, though there were still ways for

which lesbians could be charged, for example by being deemed dangerous to

the state, or simply being detained by the state even if their behavior

was not criminal. Prominent lesbians of this period included

Lucía Sánchez

Saornil, América Barroso,

Margarita Xirgu,

Irene Polo,

Carmen de Burgos,

María de Maeztu,

Victoria Kent and

Victoria Ocampo.

Born Ramona Victoria Epifanía Rufina Ocampo in Buenos Aires into a high society family, she was educated at home by a French governess. She would later write, "the alphabet-book in which I learned to read was French, as was the hand that taught me to draw those first letters."[1][2] Her sister, Silvina Ocampo, also a writer, was married to Adolfo Bioy Casares.

She is sometimes said to have attended the Sorbonne: on page 39 of her biography of Ocampo, Doris Meyer states that, during the family's 1906–1907 trip to Paris, the same during which she was etched by Paul César Helleu, the Ocampos allowed 17-year-old Victoria, "well-chaperoned", to audit some lectures at the Sorbonne and at the Collège de France. She remembered particularly enjoying Henri Bergson's lectures at the latter. She never matriculated at either. Her old traditional wealthy family frowned on formal education for women, so Victoria had little. In 1912, Ocampo married Bernando de Estrada (aka Monaco Estrada). The marriage was not happy, and in 1920, the couple separated, and Ocampo began a long–lasting affair with her husband's cousin Julián Martínez, a diplomat.[3][2]

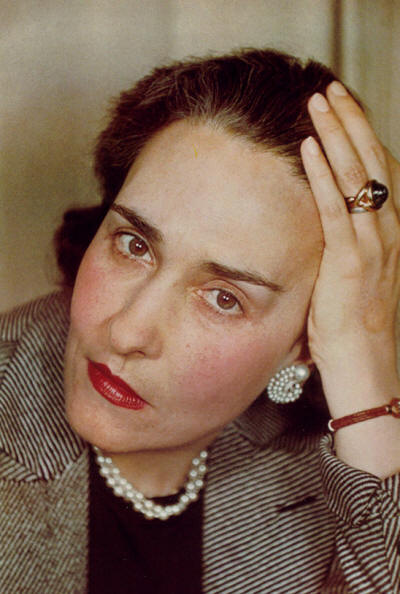

Victoria Ocampo, 1939, by Gisèle Freund

In Buenos Aires, she was a lynchpin of the intellectual scene of the 1920s and 1930s. Her first book, written in French, was De Francesca à Beatrice (1923?), a commentary on Dante's Divine Comedy. Other works include Domingos en Hyde Park; El Hamlet de Laurence Olivier; Emily Brontë (Terra incógnita); a series called Testimonios (ten volumes); Virginia Woolf, Orlando y Cía; San Isidro; 338171 T.E. (Lawrence of Arabia) (a biography of T. E. Lawrence) and a posthumously published autobiography. There is also an edited book of dialogues between Ocampo and Borges.[2]

Ocampo corresponded with Virginia Woolf in the later 1930s; the two writers met in London in June 1939 but the meeting was not a success. [4]

Perhaps of greater significance than her own writing, she was founder (1931) and publisher of the magazine Sur, the most important literary magazine of its time in Latin America. Among the writers published in Sur were Jorge Luis Borges, Ernesto Sabato, Adolfo Bioy Casares, Julio Cortázar, José Ortega y Gasset, Manuel Peyrou, Albert Camus, Enrique Anderson Imbert, José Bianco, Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Waldo Frank, Gabriela Mistral, Eduardo Mallea and Silvina Ocampo (her younger sister).[5]

In 1935, Ocampo expressed some approval for Benito Mussolini with whom she was granted an interview in March of that year in Rome, hailing him then as "genius" and Caesar reborn.[6] "I have seen Italy in blossom turn its face towards him."[7] However, she was never a convinced fascist sympathizer, and expressed disapproval of Mussolini's conservative views on gender roles and the regime's growing militarism.[8] By the time her interview with Mussolini was published in August 1936, Italy had invaded Abyssinia and Ocampo appended a note to it declaring that any hope that the fascist regime might improve was lost and criticized those in Argentina who supported Italy's belligerence.[9]

In 1937 Ocampo and the editors of Sur came out openly against fascism and definitively linked the journal with liberalism.[10] During the Spanish Civil War, the magazine sided with the Republicans.[11] She supported and edited from Argentina in collaboration with her friend and translator, Pelegrina Pastorino, the anti-Nazi magazine Lettres Francaises, directed by Roger Caillois and in 1946 she was the only Argentinean who attended the Nuremberg Trials. A few months before World War II, in 1939, Ocampo is appointed to the International committee on intellectual cooperation (League of Nations, Geneva) but does not participate in its works.[12] In 1953, Ocampo was briefly imprisoned for her open opposition to the government of Juan Domingo Perón.[13]

She was made a member of the Argentine Academy of Letters in 1976 (the first woman ever admitted to the Academy; she formally took her seat on 23 June 1977). The "cultural dialog", initiated in 1977 by the de facto government but organized by UNESCO, was held in her home, Villa Ocampo, in San Isidro, Buenos Aires Province; she eventually donated the house to UNESCO in 1943.[14]

At "Villa Ocampo" Igor Stravinsky, André Malraux and Rabindranath Tagore had been her guests, also Indira Gandhi, José Ortega y Gasset, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Ernest Ansermet, Rafael Alberti, etc. Graham Greene dedicated his 1973 novel The Honorary Consul to her, "with love, and in memory of the many happy weeks I have passed at San Isidro and Mar del Plata".

Victoria Ocampo died in Buenos Aires in 1979, and is buried in La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires.[15]

My published books: