Partner Toer van Schayk

Queer Places:

Nederlands Dans Theater, Spuiplein 150, 2511 DG Den Haag, Netherlands

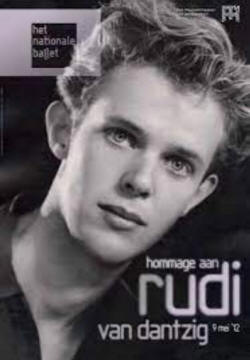

Rudi van Dantzig (August 4, 1933 – January 19, 2012), as artistic director and resident choreographer of the Dutch National Ballet from 1971 to 1991, brought his company to international attention with a repertory that embraced works of both

classical elegance and modern energy. He created a body of choreographic work that explores liberation,

hope, and the place of homosexuality in our time, as well as such controversial issues as abuses of power. On Christmas Day 1968

Rudolf Nureyev opened in Rudi van

Dantzig’s Monument for a Dead Boy – about a boy becoming gay – with the Dutch

National Ballet in The Hague. He then persuaded the Royal Ballet in London to

commission van Dantzig to choreograph a new ballet, The Ropes of Time, which

was premiered on 2 March 1970. As a homosexual with an active political sensibility, van Dantzig felt acutely the intolerance of his times, and this became a major theme in his ballets and his writings. He shared his life and career with his partner

Toer van Schayk, a dancer, set and

costume designer, and choreographer with the Dutch National Ballet.

Rudi van Dantzig (August 4, 1933 – January 19, 2012), as artistic director and resident choreographer of the Dutch National Ballet from 1971 to 1991, brought his company to international attention with a repertory that embraced works of both

classical elegance and modern energy. He created a body of choreographic work that explores liberation,

hope, and the place of homosexuality in our time, as well as such controversial issues as abuses of power. On Christmas Day 1968

Rudolf Nureyev opened in Rudi van

Dantzig’s Monument for a Dead Boy – about a boy becoming gay – with the Dutch

National Ballet in The Hague. He then persuaded the Royal Ballet in London to

commission van Dantzig to choreograph a new ballet, The Ropes of Time, which

was premiered on 2 March 1970. As a homosexual with an active political sensibility, van Dantzig felt acutely the intolerance of his times, and this became a major theme in his ballets and his writings. He shared his life and career with his partner

Toer van Schayk, a dancer, set and

costume designer, and choreographer with the Dutch National Ballet.

Born in Amsterdam on August 4, 1933, van Dantzig was six years old when the German Army invaded the Netherlands. During the following five years, van Dantzig grew up under the Nazi Occupation, and for a particularly formative period was separated from his parents when he was sent to stay in the countryside, which presumably was safer from combat and bombing. In his prize-winning autobiographical novel For a Lost Soldier (1991), van Dantzig recounts the harsh experiences of wartime from a child's perspective, including the story of a post-Liberation love affair between twelve-year-old Jeroen (the character standing in for van Dantzig) and a young (though significantly older than twelve) Canadian soldier who arrives with the Allied troops in 1945. Running through the novel are themes of the loss of youthful innocence and the complexity of relationships in an atmosphere of aggression and fear. Not surprisingly, these same themes recur time and again in van Dantzig's choreography. (For a Lost Soldier was adapted into a 1994 film of the same title, written and directed by Roeland Kerbosch.) Classic adolescent problems, complicated by his wartime memories and premature introduction to adult sexuality, emerged after van Dantzig's return to Amsterdam. Uninterested in most of his schoolwork, he was a troubled student and dreamed of becoming a painter. Then one day, when he was fifteen, he wandered into a movie theater to be swept away by the film on view. The movie was not about a painter he might wish to become, however; the movie was The Red Shoes, Michael Powell's 1948 dance-filled masterpiece about a ballerina torn between a diabolical impresario and a struggling composer. From that moment on, van Dantzig's sole obsession was to become a dancer. He studied first with Anna Sybranda before finding his way to the studio of Sonia Gaskell, a former Ballets Russes dancer who ran a small company and school in Amsterdam at that time. By his own admission, van Dantzig was at a severe disadvantage since he had had no dance experience and was starting late. He was fortunate, however, as Gaskell overlooked his deficiencies and focused on his zeal and intelligence. Once he slipped into Gaskell's realm, van Dantzig worked hard, became a company member, and by 1955 had choreographed his first dance, Nachteiland (to a score by Claude Debussy). Because Gaskell and her dance companies were dedicated to a classical and Diaghilev-style ballet repertory, he was not prepared for the impact that modern dance would have on him. Seeing his first Martha Graham performance hit van Dantzig like a bombshell. With a larger choreographic world opened to him by Graham's expressiveness and power, he traveled to New York to study her technique. Upon returning to Amsterdam, the intense and mercurial van Dantzig became embroiled in disagreements with Gaskell and eventually decided to join ranks with Hans van Manen and Benjamin Harkarvy in 1959 to found The Netherlands Dance Theatre. After a year with the new group, however, van Dantzig found himself dissatisfied and drifted back to Gaskell (whose company combined in 1961 with the Amsterdam Ballet to become the Dutch National Ballet). Upon Gaskell's retirement in 1968, he and another dancer, Robert Kaesen, took over the reins of the Dutch National Ballet; van Dantzig assumed the sole directorship in 1971. Being in charge of the company suited van Dantzig. He possessed the rare combination of administrative ability and an unwavering drive to create dances as powerful as Monument to a Dead Boy (1965, with a score by Jan Boerman), which created a sensation at its premiere. Choreographed before van Dantzig shouldered administrative responsibilities, that piece explored innocence and corruption in homoerotic desire and offered ballet superstar Rudolf Nureyev his first role in a modern work. Van Dantzig subsequently created three more ballets for Nureyev.

My published books: