Queer Places:

16 Bretton Rd, West Hartford, CT 06119

The Penn-Post Hotel, 304 W 31st St, New York, NY 10001

Hotel America, 145 W 47th St, New York, NY 10036

426 W 56th St, New York, NY 10019

Murray Gitlin (April 12, 1927 - June 15, 1994) was a dancer and stage manager.

Murray Gitlin (April 12, 1927 - June 15, 1994) was a dancer and stage manager.

During World War II, the U.S. military created a climate of anxiety and prejudice for gay recruits through both formal screening and media-fueled fears. Military psychiatrists coined specific, often derogatory terms to categorize gay servicemen based on their perceived intent regarding military service: "Malingerers" referred to those who pretended to be gay to avoid combat duty at the front. "Reverse malingerers" described gay recruits who pretended to be heterosexual so they could perform their "patriotic duty." By 1943, the prejudice became institutionalized through screening tools like the Cornell Selectee Index. This index used "occupational choice" to screen out men in professions stereotyped as effeminate (such as dancers, window dressers, and interior decorators), based on the assumption that they would have difficulty with their "acceptance of the male pattern." The media amplified this official prejudice. The Washington Star reported that Navy psychiatrists would "be on the lookout for... homosexuality," and Time noted that the question "How do you get along with girls?" was "machine-gunned" at inductees during their physicals. These widely spread reports created intense and often unlikely fears among gay men enlisting. Murray Gitlin, who was born in West Hartford, Conn., recalled his anxiety when enlisting in the Navy: "I was very afraid that they would undress me during the physical examination, and they'd know, looking at me, that I was gay. That's how innocent I was. Well they didn't, and they couldn't have cared less." Gitlin's experience highlights the gap between the pervasive, media-driven fear of detection and the reality of the often-impersonal military induction process.

Gitlin was working in the terminal cancer ward of the Brooklyn Naval Hospital but dedicated his nights off to visiting Manhattan, dreaming of becoming a dancer after the war. "Treated Like Royalty": He notes that servicemen, all in uniform, were highly celebrated and "treated like royalty," receiving perks like free tickets to movies and concerts. This social privilege, however, was layered with the danger of discovery due to the military's anti-homosexuality policies. While at Radio City Music Hall alone and in uniform, Gitlin, who described himself as "too fat" to be a "hot sailor," was approached by a "tall blond man" who sat next to him. The public nature of the encounter was striking, as the man placed his hand on Gitlin's thigh and "kept fooling around" in the orchestra of the Music Hall during the movie (Abe Lincoln in Illinois). Gitlin was so nervous he began to tremble. The man invited Gitlin to his hotel room, located at the Hotel America on 47th Street, between Sixth and Seventh. Gitlin described the hotel with a vivid, romanticized image: "like a hotel that Tennessee Williams would have stayed in, in New Orleans, louvered doors and very rinky, dink." The arrangement—waiting downstairs, then being let into the room—provided a clandestine moment for their connection. Gitlin recalls the profound emotional impact of the embrace, exclaiming, "I love you!" The man turned out to be a cocktail pianist from Asbury Park, whom Gitlin found "very corn-fed and very middle of the road," suggesting he was surprisingly ordinary, despite the extraordinary circumstance. Gitlin calls the experience a "great release and a great experience," confirming that despite the immense pressure and fear of military exposure, he was able to find genuine, repeated connection in the urban environment.

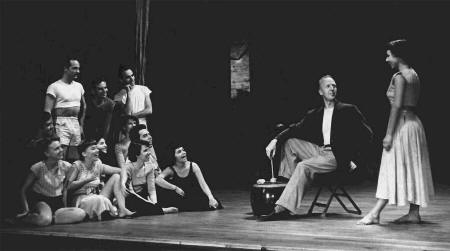

Murray Gitlin studied with Hanya Holm, Alwin Nikolais, Martha Graham and José Limón, and danced with the New York City Opera, the companies of Nikolais and Pearl Lang, and in such musicals as "The King and I," "The Golden Apple," "Can-Can" and "Irma la Douce."

Murray Gitlin had black hair and a long, attractive Semitic face. His low, warm, carefully modulated voice and precise diction made him sound almost British. His close friend Stanley Posthorn remarked that Gitlin was so charming that he could convert anyone he met into a friend. In 1949, Gitlin moved back to New York, initially staying at the elegant apartment of his uncle Aaron and aunt Helen on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx. At age twenty-two, he was focused solely on becoming a dancer, explaining, "I was a late starter, and I didn't have time to waste." His Aunt Helen, suspicious because of the association between male dancers and homosexuality, confronted him. Gitlin, respecting her "balls" in asking such a question in 1950, openly affirmed his identity: "Well, Helen, I am... I've accepted it, and I think I understand it." Though Aunt Helen insisted he consult her psychiatrist, the session had no effect, as Gitlin already felt confident and convinced that there was "never any choice" for him. Gitlin found an unconventional but affordable home: a magnificent cold-water flat at 426 West 56th Street with a bathtub in the kitchen and the bathroom in the hall, renting for only $16 a month. He would remain in that West Side neighborhood for the next forty-four years. His first job was in the chorus of the prestigious Broadway production of The King and I. This role held great significance for him, as he was "very happy to be in that show" and considered it "the most important" theatrical experience of his career. In the chorus line, Gitlin replaced Otis Bigelow, a notorious figure in gay social history, known for having chosen a sailor over a millionaire in the 1940s. Gitlin had previously met Paul Taylor at Martha Graham's dancing school in Vermont. Taylor, whom Gitlin thought looked like a swimmer, was very shy. Their real friendship began later when Gitlin saw Taylor waiting for him outside the St. James Theatre. Gitlin found Taylor an apartment in his building, turning their home into an accidental artistic hub. Taylor brought over his painter friend, Bob Rauschenberg. Gitlin recalled Rauschenberg's unusual artistic eye for his own humble decorating efforts. After going to the bathroom, Rauschenberg declared that Gitlin's attempts to "cheer up" the peeling, brightly painted red and orange bathroom would be part of an exhibit "when I become famous." Choreographer Jerome Robbins (who choreographed The King and I) was another frequent visitor. Gitlin noted that they "really liked one another" and shared a love for games on Fire Island. Robbins later used a photograph of actors Larry Kert and Carol Lawrence standing in front of Gitlin's West Side apartment building to illustrate the cast album of his monumental musical, West Side Story. Gitlin noted that despite their early closeness, something eventually "snapped," reflecting Robbins's reputation for turning people away, a trait Gitlin called "weird."

Gitlin had an extensive career as a stage manager, handling diverse theatrical productions both Off-Broadway and on tour: He served as stage manager for revivals of musicals and plays like On the Town, The Boys From Syracuse, and Private Lives. He was also production stage manager for the Broadway revival of Blithe Spirit (with Richard Chamberlain) and for touring productions of major works including Long Day's Journey Into Night, Death Trap, and Brian Bedford's one-man show, Poets, Lunatics and Lovers. Gitlin's most significant contribution was his dedication to The Boys in the Band: Gitlin was the production stage manager for the play from its first workshop production (on Vandam Street) throughout its initial Off-Broadway run and first national tour. Written by Mart Crowley, the play offered the first "uncloseted" look at white, male, middle-class gay life in a New York setting, capturing its complex mix of "brittle intelligence, bitter humor and exaggerated pathos." The title was inspired by a line from the film A Star Is Born, where James Mason tells Judy Garland, "Relax, it's three A.M. at the Downbeat Club, and you're singing for yourself and the boys in the band." Crowley's agent was initially so embarrassed by the script—likening it to a "weekend on Fire Island!"—that she couldn't send it out. However, Crowley found immediate support from producers Richard Barr and Charles Woodward, Jr. Gitlin noted that the play only truly "worked" after Crowley and director Bob Moore significantly cut the script in half from the original version. Leonard Frey gave a brilliant performance as Harold, the guest of honor. Harold's self-introduction in the second act became famous for its brutal honesty: "What I am, Michael, is a thirty-two-year-old, ugly, pock-marked Jew fairy..." Gitlin personally suggested and asked Robert La Tourneaux to audition for the role of Tex, the laconic $20-a-night hustler given as Harold's birthday present. Gitlin met the "beautiful young man" at the Westside YMCA. La Tourneaux initially hesitated, finding the role "demeaning," but ultimately accepted and repeated the role for the subsequent film adaptation. The Boys in the Band perfectly timed the social changes of the late 1960s, quickly becoming a defining piece of American theatre and a foundational work for LGBTQ+ representation.

Murray Gitlin died on June 15, 1994, at St. Clare's Hospital. He was 67 and lived in Manhattan. The cause was AIDS.

My published books: