Partner Eugene Kurtz

Julien Outin

(June 20, 1923 - December 28, 2002), a painter and printmaker, was born in the picturesque village of Landernau in the department of Finistère in Brittany. He went to study in Paris as a young man and lived and worked there for the rest of his life.

Julien Outin

(June 20, 1923 - December 28, 2002), a painter and printmaker, was born in the picturesque village of Landernau in the department of Finistère in Brittany. He went to study in Paris as a young man and lived and worked there for the rest of his life.

Julien Outin moved to Paris just before the Second World War. He lived at a pension de famille in rue Saint-Andre-des-Arts. The pension was home to a number of artists and also to a number of Jewish refugees, and it seems likely that is where he met Boris Taslitzsky. Banker Jean Nicolas, friend of Outin, remembers Julien speaking of Taslitzky and also of the artist Andre Fougeron, with whom Taslitzky worked on murals for public schools in the Paris suburbs.

After the Second World War, Outin was part of a circle of young artists, many American, including Ellsworth Kelly and Avel De Knight, who were in Paris studying under the G. I. Bill. His long-time companion was the American composer of contemporary classical music, Eugene Kurtz. Kurtz dedicated Three Songs from Medea to Outin.

Outin's work was included in the 1992 exhibition at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris: De Bonnard à Baselitz - Dix ans d’enrichessements du Cabinet des Estampes, 1978-1988 (From Bonnard to Baselitz - Ten Years of Enrichment of The Print Room). His work is also in the permanent collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale.

In 1970, the French publisher Fayard brought out Ouvrages de Dames (Women’s Work), a humorous collection of collages/pen & ink drawings by Outin.

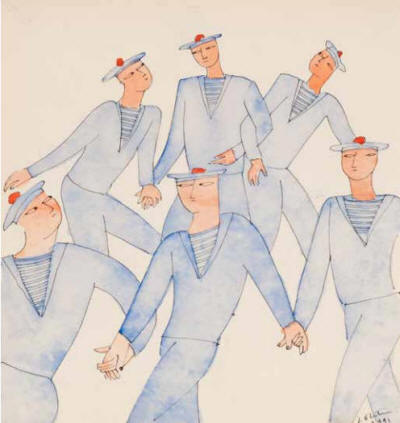

Six Dancing Sailors, 1991

watercolor, pen and ink on white wove paper

9 x 8 inches

WFG© 135834

Jean Nicolas was the executor of his estate. Nicolas worked for several months with Eugene Kurtz, to settle the estate and to clear out the contents of Outin's studio, a lifetime accumulation of art and other possessions. Many of the most valuable works of art, including a number of early drawings by Ellsworth Kelly, whom Outin had known as a young art student, were sent to auction, sold privately, or given away. One night, Nicolas found Kurtz, elderly, ill, and exhausted, getting ready to throw out all that was left in the studio. On top of the trash pile that was about to be taken out to the street was a portfolio of un-stretched oil paintings and works on paper. Jean spotted it, looked through it, and told Kurtz that he would like to show it to the Fletcher/Copenhaver Fine Art (owned by Joel L. Fletcher and John Copenhaver), for he thought they might be interested in purchasing it, which they did. The portfolio contained a number of works by friends of Outin: paintings and drawings by the African-American painter Avel C. de Knight, who studied in Paris after the Second World War and remained close to Outin throughout his life; a dozen or so drawings and paintings signed and some of them were not. Among them was one small, haunting pencil drawing of a bald and emaciated man in an overcoat seated on a bench and, next to this figure, two studies of gaunt faces in profile. The drawing was signed and inscribed twice. It was signed Boris Taslitzky/ 45 and above that signature and date was an inscription in French: In witness of a very old friendship, Boris followed by the date 46. It was one of the drawings that Taslitzky made while interned in Buchenwald concentration camp, drawings later published in an album and considered major works of art bearing witness to the horror of the Holocaust. Boris Taslitzsky was born in Paris to Russian Jewish refugees. When he was four years old, his father was killed in combat in World War I. At the age of seventeen, he began his studies at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and later studied with sculptor Jacques Lipchitz and tapestry designer Jean Lurat. No doubt influenced by his experiences as the son of Jewish refugees, Taslitzsky early identified with Leftist causes and used his art to portray social problems in Europe, much as Social Realist artists like the Soyer brothers and Ben Shahn were doing at the same time in the United States. In 1939, Taslitzsky was imprisoned by a military tribunal for having executed several drawings intended for Communist propaganda. He spent time is various jails before being transferred to the French prison of St. Sulpice near Toulouse. While there he painted frescoes on the walls of seven cells, using paint that was supplied to him by the archbishop of Toulouse. He escaped from St. Sulpice and joined the French Resistance. He was recaptured by the Nazis in 1941 and sent back to Saint Sulpice. In 1944, along with 662 other prisoners, he was deported to Buchenwald. According to his obituary in the European Jewish Press: From the moment of his arrival (at Buchenwald), Taslitzsky was determined to do what he could to record what he saw, both as a way of resistance and as a testimony for the future. He participated in the clandestine life of the camp and received help to be able to draw. People supplied him with paper, pencils, and watercolors. He made his drawings on fragments of Nazi circulars and sheets of stolen Ingres paper. And he risked his life to paint scenes of daily life, a series of portraits, expressions of dead people. Buchenwald was liberated in April of 1945 and Taslitzsky returned to Paris with about 100 of his drawings and four of his watercolors. In 1946 the writer Louis Aragon published them in an album entitled 111 Drawings Made in Buchenwald. Taslitzky later wrote: If I go to Hell, I will draw what I find. After all, I have already been there and drawn it.

In addition to the drawing, the almost-discarded portfolio contained a handsome, unsigned oil portrait of a youthful Outin. Because if its similarity to other portraits by Taslitzky, the portrait of Julien is almost certainly also by him. In 2009, Fletcher and Copenhaver presented the drawing to the U. S. Holocaust Museum in memory of their friend, Holocaust scholar Bryan Burns. Bryan, who died of cancer in 2000, was instrumental in starting the first master's degree program in Holocaust Studies in Britain at the University of Sheffield where he was a professor of English. On accepting the Taslitzky drawing for the U. S. Holocaust Museum, Kyra Schuster, Curator of Art and Artifacts for the Museum, said: We are incredibly honored to receive the drawing for our permanent collection. Many of the drawings that Taslitzky made at Buchenwald are in the Museum of National Resistance, a museum in the suburbs of Paris that is dedicated to the history of the Resistance. His works are also found in a number of major museums, including the Pompidou Center in Paris and the Tate Gallery in London. While the rare book room of the Holocaust Museum has a copy of the 1946 album in which the drawing is reproduced, this was the first piece of original artwork by Taslitzky in the Museum's collection.

My published books: