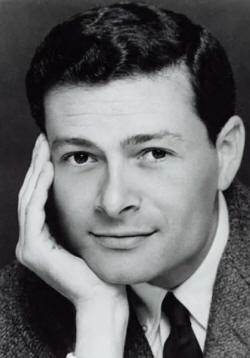

Partner Marty Finkelstein

Queer Places:

Mount Moriah Cemetery

Fairview, Bergen County, New Jersey, USA

Gerald Sheldon "Jerry" Herman (July 10, 1931 – December 26, 2019) received his bachelor’s degree in 1953 and moved to

New York, where he made his living writing special material for such

performers as Ray Bodger, Tallulah Bankhead, and Hermione Gingold and

playing piano in cocktail lounge. Herman’s hit Hello Dolly! opened on

January 16, 1964, based on Thornton Wilder’s play The Matchmaker. It was

not until 1983, when Le Cage aux Follies opened, that a Jerry Herman show

again enjoyed blockbuster status on the Broadway stage. When Le Cage aux

Follies won six Tonys, including those for best musical and best score,

Herman attended with his lover and business partner, Marty Finkelstein,

who died of AIDS in 1989 at the age of 36. They had met in 1983 and

Finkelstein was a space planner and designer. Jerry Herman and Marty Finklestein

moved to Key West in the early 1980s and set about restoring and

renovating multiple grande dame Victorian homes.

Gerald Sheldon "Jerry" Herman (July 10, 1931 – December 26, 2019) received his bachelor’s degree in 1953 and moved to

New York, where he made his living writing special material for such

performers as Ray Bodger, Tallulah Bankhead, and Hermione Gingold and

playing piano in cocktail lounge. Herman’s hit Hello Dolly! opened on

January 16, 1964, based on Thornton Wilder’s play The Matchmaker. It was

not until 1983, when Le Cage aux Follies opened, that a Jerry Herman show

again enjoyed blockbuster status on the Broadway stage. When Le Cage aux

Follies won six Tonys, including those for best musical and best score,

Herman attended with his lover and business partner, Marty Finkelstein,

who died of AIDS in 1989 at the age of 36. They had met in 1983 and

Finkelstein was a space planner and designer. Jerry Herman and Marty Finklestein

moved to Key West in the early 1980s and set about restoring and

renovating multiple grande dame Victorian homes.

"I have always been drawn to outrageous, larger-than-life female characters," writes Jerry Herman in a memoir of his career as a Broadway composer and lyricist. So it is not surprising that, although seemingly retired from the musical comedy stage, he remains the best proponent of the "diva musical," described by theater historian John Clum as a musical comedy "about a woman's escape from the humdrum" and pedestrian life to which social convention would consign her. More importantly, as Clum also notes, the diva musical allows a gay theater audience "an escape from the oppressive life into magic" through worship of a female star who has no hesitation--in the words of Herman's Zaza--to "put a little more mascara on" and turn the world into something "ravishing, sensual, fabulous, . . . glamourous, elegant, [and] beautiful." Thus, Dolly Levi "puts her hand in" and rearranges everyone's life for the better; Mame Dennis coaxes the blues right out of the horn and teaches everyone to celebrate simply because "it's today"; actress Mabel Normand lights up not only the movie screen but every room she walks into; Mrs. Santa Claus restores childhood innocence, advocates gender equality, and saves Christmas; and transvestite extraordinaire Zaza proudly boasts "I am what I am" while teaching sour moralists that "the best of times is now."

Born July 10, 1931, to middle-class Jewish parents in Jersey City, New Jersey, Herman was the only child of ardent theater-goers who introduced him to the joys of the Broadway musical at an early age. His family ran a summer camp where Herman worked until he was 21, in the process discovering a talent for producing musical entertainments. An audition for Frank Loesser (Guys and Dolls) encouraged Jerry to work full time as a composer, and after writing the music for three off-Broadway plays, he scored a major success with Milk and Honey (1961). Shortly thereafter David Merrick hired him to write the music and lyrics for Hello, Dolly! (1964; film 1969), and for the next twenty years Herman was one of the most bankable talents on Broadway. Mega-hits such as Mame (1966; film 1974) and La Cage aux Folles (1983) alternated with box office failures such as Dear World (1969) and Mack and Mabel (1974) that nonetheless quickly attained cult status. In addition to a revue of songs from his shows (Jerry's Girls, 1985), Herman has written the scores for the musically less-interesting The Grand Tour (1979) and for Mrs. Santa Claus (1996), a television musical created for Angela Lansbury that has become a stalwart of the Christmas holiday season. Despite a highly popular thirtieth anniversary revival of Hello, Dolly! and a much-applauded London concert version of Mack and Mabel (1988), Herman laments in his memoirs the end of the era of "upbeat, feel-good" musicals such as those he enjoys writing. He is no longer creating original work for the theater. There are three constants in a Herman show.

First, there is what Herman himself calls the "statement song" in which the heroine delivers her philosophy of life. For example, Dolly Levi liberates her spiritual nemesis Horace Vandergelder's overworked, underpaid clerks by telling them to "Put on Your Sunday Clothes" and venture from rural Yonkers into Manhattan to discover that "there's lots of world out there." Mame Dennis throws extravagant parties for no special occasion, insisting simply that "It's Today"; in "Open a New Window," she teaches her nephew Patrick that the only "way to make the bubble stay" is by resisting convention and experiencing something new every day. Aurelia, the Madwoman of Chaillot, counsels the denizens of her quarter of Paris that hope is reborn "Each Tomorrow Morning," which is what allows her to go on whenever she feels dejected. And drag star Zaza teaches her neighbors and audience to "hold this moment fast / And live and love as hard as you know how, / And make this moment last / Because the best of times is now." Herman's heroines do not hesitate to interfere--always generously, always joyously--in other characters' lives, in particular teaching the younger generation how to live more freely and with greater satisfaction. Their philosophy is clearly Herman's own, and that of the chorus in Mack and Mabel, which asserts its refusal to be cowed by disappointment and instructs the audience to "Tap Your Troubles Away."

Second, every Herman play allows the diva a musical dramatic soliloquy. The song marks a moment of selfdoubt in which she rallies her spirits, even while allowing the audience to see the price that the diva pays for her optimism. Dolly sings about her loneliness in widowhood and her new-found determination to "raise the roof" and "carry on" as energetically as she can "Before the Parade Passes By." Stunned when her adult nephew seems to reject all that she taught him in youth, Mame ponders what she would do differently "If He Walked into My Life Today." Refusing to live in a world without music, laughter, love or joy, Aurelia passionately asserts that "I Don't Want to Know" that the world has turned ugly. And when confronted with his lover's son's request to absent himself when the conservative family of the boy's fiancée comes to call, Albin refuses to hide who he is, insisting that "Life's not worth a damn / Till you can say / 'Hey, world, / I am what I am!'" Such songs are invariably the most dramatic moment in the play, demonstrating the indomitable spirit that makes each Herman protagonist a diva. Similarly, the original actor's extraordinary rendering of them is what made Carol Channing (Dolly), Angela Lansbury (Mame, Aurelia, Mrs. Santa Claus), and George Hearn (Albin) stars, and kept their dangerously over-the-top performances from degenerating into caricature. (While Herman clearly has a particular genius for fashioning such dramatic numbers, it is important to note that he has been ably aided by the directors and set designers of his shows. A semi-circular runway extending around the orchestra pit in the original production of Hello, Dolly! allowed Channing to sing within a few feet of her audience, winning them over even while towering above them. The dramatic lighting for Lansbury's soliloquies, especially the amber gel and swirl of falling leaves as she questioned where she went wrong in "If He Walked into My Life Today," transfixed audiences, winning her Tony Awards for both Mame and Dear World. And, in a piece of inspired direction, Arthur Laurents had Albin, still in drag after a performance as Zaza, pull off his wig at the conclusion of "I Am What I Am" and proudly exit down the center aisle, to the thrilled applause of the audience, at the close of La Cage's first act. Herman's directors have created big theatrical gestures that magnify the inner resolve of these larger-thanlife women.)

And, finally, every Herman play offers a "staircase number" in which the assembled company, in a pull-outall- the-stops fashion, celebrates its transformation by praising the woman who raises the energy level of everyone around her by her mere presence. Dramatically, there is no reason why the waiters should be so excited about Dolly Levi's anticipated return to the Harmonia Gardens restaurant that they break into a gallop as they serve and bus tables. But theatrically, the title number of Hello, Dolly! is the occasion to celebrate Dolly's joy in living, which washes over and renews everyone whom she encounters. Likewise, the conservative Southern community into which Mame seeks to marry is so impressed by her performance on the fox hunt that crusty old Mother Burnside herself triumphantly asserts that, with Mame in their midst, "This time the South will rise again!" The chorus of Mack and Mabel celebrates Mabel's return to movie-making in a rousing number that claims that every heart beats faster "When Mabel Comes in the Room," while the chorus of Dear World is in effect praising Aurelia in the stirring finale, "One Person." The message of these songs is that the woman's presence revivifies the stodgy and pedestrian lives of her contemporaries; she brings imagination, magic, and a screwball-comedy madness to their humdrum existence. But the songs are great theatrical moments as well. Think of Carol Channing's descent down a red-carpeted staircase in a red brocade gown, with red ostrich plumes in her brassy yellow hair, or the jubilant cakewalk on the terrace of an antebellum mansion as the company sings the title song of Mame, or Les Cagelles in their highest drag forming a sequined constellation around Zaza. These are moments of glorious, jubilant theatricality that celebrate a woman whose strength of character and comic imagination allow her to resist the pressures of social convention and recreate herself as something bigger, brassier, and livelier than decorum allows. Such moments, like the characters themselves, are a drag queen's dream.

While audiences have generally been enthusiastic--often wildly so--concerning Herman's work, a gay backlash emerged against him in the early 1980s, paradoxically just as he became most highly visible in popular gay culture. In part, the backlash reflects a change in musical tastes that began earlier but was only fully developed in the 1980s. Their very identity as diva musicals puts Herman's plays at odds with the "concept musical," which in Martin Gottfried's definition places greater importance on the weaving of music, lyrics, dance, stage movement and dialogue "in the creation of a tapestry-like theme (rather than in support of a plot)," and so is less likely to focus upon a single star. An ensemble ethos marks the groundbreaking musicals of the 1970s, such as Company (1970), Chicago (1975), and A Chorus Line (1975). Indeed the "One" number performed by the dancers auditioning for the play-within-the-play of A Chorus Line seems to parody the staircase song that Herman specializes in, the point of A Chorus Line being that there is no single star, but that everyone contributes to the ensemble. More problematically, however, the backlash signaled gay culture's rejection of Herman's basic philosophy. Survival, for Herman, is a question of posture and attitude; one simply has to "put on your Sunday clothes / When you feel down and out" or "put a little more mascara on." But while tapping one's troubles away may have appealed to a generation raised on post-Depression era Busby Berkeley movie musicals, increased public awareness of the spreading AIDS epidemic gave the lie to La Cage's claim that "The Best of Times Is Now." Resistance through grand gestures is the pose of both the diva and the drag queen; AIDS required a different theater of resistance, black comedy rather than screwball comedy. Commenting upon the sudden reversal of opinion concerning La Cage aux Folles in the mid-1980s, Mark Steyn--in an aggressively homophobic account of the Broadway musical-- notes that "One minute . . . [it] was the biggest homegrown hit of the day; the next it was gone," largely because as public perception of AIDS grew, "fags weren't funny anymore; fags meant disease and death." Stephen Sondheim's questioning his audience's ability to live with ambivalence seemed a braver and more realistic form of engagement in the 1980s than Herman's asking it to choose self-consciously to ignore tragedy and assert joy. As Herman himself observes, "the upbeat, feel good songs that I write" no longer resonated with audiences. Criticism of Herman's optimism as escapist is unfair. There is a strong satiric impulse in such songs as "Masculinity," "It Takes a Woman," and "The Spring Next Year" that is every bit as socially engaged as Burton Lane's much lauded challenge to American racism in Finian's Rainbow. Ironically, however, the moment when Albin, refusing to fashion himself to suit anyone else's expectations, pulls off his wig at the end of "I Am What I Am" was not only the very moment when gays asserted themselves most openly on the Broadway stage; it was also the moment when American gay culture lost its need of a diva to voice its concerns and became free to raise them in its own voice. Thus, Herman's plays seem dated to newer gay audiences raised on Sondheim's ambivalence and on the openly gay musicals of William Finn in which characters do not need musicals to feel good about themselves. Even as La Cage aux Folles made homosexuality the undisguised subject of a popular musical, challenged the hypocrisy of the self-proclaimed moral majority empowered by the presidency of Ronald Reagan, and provided gays with a national anthem ("I Am What I Am"), Herman found himself bypassed by the very parade that he had been leading.

My published books: