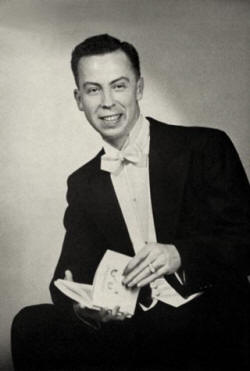

Partner Jim Kepner, Albert Ross Puryear

Queer Places:

209 N Poplar St, Bristow, OK 74010

James Fugaté (February 13, 1922 - March 28, 1995) published the novel Quatrefoil and other works under the pseudonym James Barr, an alias he

also used in his work as an activist in the homophile movement of the 1950s. He

was briefly lovers with Jim Kepner. He became

involved with con artist

Albert Ross Puryear.

James Fugaté (February 13, 1922 - March 28, 1995) published the novel Quatrefoil and other works under the pseudonym James Barr, an alias he

also used in his work as an activist in the homophile movement of the 1950s. He

was briefly lovers with Jim Kepner. He became

involved with con artist

Albert Ross Puryear.

Fugaté was born on February 13, 1922 in Hallett, OK, an oilfield boomtown. His mother died of childbed fever; he never knew his father. Fugaté's illegitimate birth haunted him as a child, but his adoptive parents, who had money from wheat and oil in Kansas, gave him a good education. His best-known work, the novel Quatrefoil (1950), is based on his experience in the U.S. Navy during World War II, but a central character is patterned after a fraternity brother with whom Fugaté had sex as a university student at University of Oklahoma. Early in 1942 Fugaté enlisted in the U.S. Navy and sailed from San Francisco for Guadalcanal, but on returning to the United States, he went through Officers Training in Chicago. After the war, he returned to the university in 1946 to study professional writing, but after three semesters he left for New York City, where he earned money by writing advertising copy for television and worked on Quatrefoil, which was published in 1950 by Greenberg, a somewhat marginal publishing house that was attempting to reach a gay readership at a time when homosexuals were feeling especially embattled by Cold War hysteria and McCarthyism. In 1977, evaluating the novel from a gay liberation perspective, literary critic Roger Austen described Quatrefoil as follows: "James Barr's Quatrefoil is one of the most intelligently written of American gay novels, with the author's lofty intellectualism appearing somewhat of a mixed blessing as the novel is reread today. The two main characters are Phillip Froelich and Tim Danelaw, naval officers who meet in Seattle in 1946, fall in love, and finally become lovers. Both are wealthy, erudite, civilized: they can speak in French or German, discuss art and philosophy with epigrammatical grace, and they value themselves as vastly superior to the average homosexual, who is always sliding 'further toward degeneracy.'" Despite the novel's disdain for average homosexuals, Austen concludes that "Its two thoughtful, masculine heroes provided a corrective to the many mindless, pathetic or flighty gay characters of the forties. Quatrefoil is one of the earliest novels that could have produced a glow of gay pride." Indeed, homosexuals--especially those who were members of the emerging homophile movement-- welcomed Quatrefoil as a sympathetic portrayal of same-sex love, though the death of one of the lovers in an auto accident limits the development of the relationship. Gay readers also welcomed--though to a lesser degree--Fugaté's second book, the collection of short stories Derricks (1951), which, Austen noted, "is full of stories about finding down-to-earth men to love in the Midwest." In 1951 Fugaté went to Los Angeles with the intention of writing for the movies, but early in 1952 he volunteered to return to active duty as a reserve officer in the Navy and was sent to a base in Alaska. While reviewing his Top Secret clearance, the Office of Naval Intelligence learned that he was the author of Quatrefoil. This led to an eight-month interrogation that resulted in a General Discharge Under Honorable Conditions. That persecution politicized Fugaté. He no longer saw homosexuality as his personal problem, which he had been fighting by trying to be "normal," but as a social condition that merited understanding and acceptance by the society as a whole. Consequently, he became active in the homophile movement. Fugaté was in contact with One Magazine (Los Angeles) in its first year of publication in 1953 and wrote for it the short story "Death in a Royal Family." It tells how a bitchy "queen" tries to have a young man arrested as a thief by taking an overdose of what he pretends is strychnine and giving him a valuable ring to take as a "dying gift" to a friend. After calling the police to report the "theft" he discovers too late that the pretended strychnine was the real substance. The queen's "friend" had told the plot to the young man, who made the substitution--and delivered the ring to him. Fugaté ends the story wondering whether those two would live happily ever after. The story was elaborated into a play by the Swiss gay group that published the gay magazine Der Kreis and presented by them in Zurich in 1956. In the winter of 1953-54, Fugaté returned to his family in Kansas and worked as an oilfield roustabout, but he continued his contributions to One Magazine and Der Kreis, which began to publish contributions in English in 1952. He also appeared in the first issue of Mattachine Review in 1955 with an article, "Facing Friends in a Small Town," in which he described his experiences living as a known homosexual in a small Kansas town. For Der Kreis that year Fugaté wrote a vigorous defense of effeminate gay men, beginning: "A growing malady among American homosexuals today, as we are forced into a more closely united group, seems to be a particularly irrational snobbery directed against our more effeminate members." It is a very sensitive article, and all the more remarkable in that his fiction often presented effeminacy as the worst thing that could happen to a man. Also in 1955, Fugaté began a regular book column for One Magazine in which he gave personal opinions on writers of the day. The rather esoteric selection of authors--Curzio Malaparte, Kurt Singer, Arthur Koestler-- may explain why only three columns appeared. Fugaté's play Game of Fools was published in June 1955. The month before, in anticipation, he took the major step of revealing his real name in a very informative article in Mattachine Review, in which he told the story of his "Release from the Navy under Honorable Conditions." His name was given as James (Barr) Fugaté, and an editorial note disclosed that he pronounced his last name "Few-gay-tee." That name then appeared on Game of Fools. (The acute accent in his last name, and the corresponding pronunciation, may have been added as an affectation, a means of distancing himself from his Middle American background or from the unflattering similarity between his name and a vulgarity.) The play describes the arrest--and its aftermath--of four gay college students who are spending a weekend together in a cabin in the woods. In depicting the reactions of their families and the court, he exposes the pervasive religious bigotry that threatens all homosexuals. Fugaté said of religious bigotry: "I have observed, perhaps too keenly, in some of my less fortunate friends the almost incurable horrors to be suffered from the accident of believing in a faith that is totally incompatible with their natural inclinations. It seemed well to try to expose this situation, and at the same time the reverse of the medal. The result was not to be an all out attack for the annihilation of the churches as such, but rather a pattern of revolutionary thinking to point up to the individual his strength and his precious right to choose or discard as he wishes." A special number of Der Kreis in 1955 was devoted to "homoeroticism in American countries." It included a review (in French) of Les Amours de l'enseigne Froelich (1952), a French translation of Quatrefoil. The editor of the English section of Der Kreis made a German translation of Quatrefoil but was still unable to find a publisher a decade later. In October 1955 the first performance of Game of Fools was given in German in Zurich by the group associated with Der Kreis as part of their twenty-fifth anniversary celebration. (Actually, only the second act of the two-act play was presented.) In April 1956 Fugaté, now described as "one of the most controversial writers on the subject of homosexuality in this country today," reflected on the psychological state of homosexuals in an article in Mattachine Review, prompted by the murder of three boys in Chicago. In this article he pointed out the illogic in the hysteria that called for stronger laws against all sexual deviates. But, like other members of the homophile movement of the day, Barr believed that homosexuality was not a desirable state, that many homosexuals could (and should) go straight, that with the right psychiatric treatment "thousands of homosexuals might hope to lead the lives of normal men if psychiatric treatment is administered early enough and at prices they can afford to pay." Looking back, we are tempted to condemn this view as naive or even self-hating, but as Larry Kramer has pointed out: "My generation has had special, if not unique, problems. We were the generation psychoanalysts tried to change." In the early 1960s, Fugaté returned to New York and acquired an agent who helped him bring out a reprint of Quatrefoil in 1965 and his second novel The Occasional Man in 1966. Also rather autobiographical, The Occasional Man is far better written than Fugaté's first novel. The author later noted, "Though badly flawed, I still think it's the best piece of writing I've turned out." Lacking some of the "message" of Quatrefoil, The Occasional Man is quite entertaining. It also differs from Quatrefoil in presenting several gay sex scenes--in surprising detail. Barr knew New York gay life intimately, and he used his knowledge to advantage in this story of a forty-year-old trying to recover from the sudden dissolution of a fifteen-year love affair. The protagonist does so through his contacts with four contrasting men: Hermie, a black man his age, who owns a gay bar and is wise about gay life; Gus, a young movingman, who is handsome but dumb (and heterosexual, but willing to engage in a limited amount of sexual contact with men); a beautiful drifter called Pretty John; and Count de Groa, an older and enormously wealthy European (apparently an ex-Nazi living in Argentina), who is also a sexual connoisseur. This last character finally wins the protagonist. Fugaté then returned to his mother in Kansas, where he became a newspaper reporter/photographer--and enjoyed much sex. But after his mother's death in the early 1970s he collected his inheritance and returned to New York. There something occurred that years later he still could not reveal, but appears to have required him to do five years of hospital work. He returned to Oklahoma to do the hospital work. But instead of five, he worked ten years and retired with a small pension.

Fugaté died on March 28, 1995 in Claremore, Oklahoma. Although Quatrefoil was welcomed by gay activists on its original publication, it seems less positive to today's reader. As Samuel Steward wrote in his introduction to the 1982 edition, "The world of Froelich and Danelaw is . . . somewhat puzzling to the modern reader who comes across it thirty years later. He finds it difficult to understand. Yet here laid out in Quatrefoil is a graphic and accurate picture of the secrecy and concealment that was necessary in those days." James Fugaté's participation in the gay movement lasted only a relatively brief period in the 1950s. Yet his impact was strong, and his literary works are important for their illumination of a crucial time in the emerging movement for glbtq equality.

My published books: