Partner Oswald Fitzgerald

Queer Places:

Coolbeha House, Coolbeha, Listowel, Co. Kerry, V31 PE42 Ireland

Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, London SE18 4AU, UK

44 Phillimore Gardens, Kensington, London W8 7QG, UK

Queen Anne's Gate, Westminster, London SW1H 9BU, UK

17 Belgrave Square, Belgravia, London SW1X 8PG, UK

2 Carlton Gardens, St. James's, London SW1Y 5AA, UK

York House, St James's Palace, 3 Cleveland Row, St. James's, London SW1A 1DD, UK

The Broome Park Estate, Canterbury Rd, Canterbury CT4 6QX, UK

Hollybrook Memorial, Shirley, Bransgore, Christchurch BH23 8EQ, UK

St Paul, St. Paul's Churchyard, London EC4M 8AD, UK

Westminster Abbey, 20 Deans Yd, Westminster, London SW1P 3PA, UK

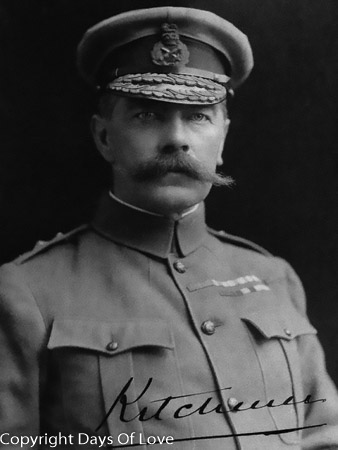

Field

Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, KG, KP, GCB, OM, GCSI,

GCMG, GCIE, PC (24 June 1850 – 5 June 1916), was a senior British Army officer

and colonial administrator who won notoriety for his imperial campaigns, most

especially his scorched earth policy against the Boers and his establishment

of concentration camps during the Second Boer War,[1]

and later played a central role in the early part of the First World War.

There is no real, plausible reason to assume that Kitchener and

Oswald "Fitz" Fitzgerald,

living together for nine years, were celibate. They lived as a couple in

dangerous times, not long after the 1895 trial of the dramatist Oscar Wilde

which led to his public humiliation, imprisonment and death in 1900.

Field

Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, KG, KP, GCB, OM, GCSI,

GCMG, GCIE, PC (24 June 1850 – 5 June 1916), was a senior British Army officer

and colonial administrator who won notoriety for his imperial campaigns, most

especially his scorched earth policy against the Boers and his establishment

of concentration camps during the Second Boer War,[1]

and later played a central role in the early part of the First World War.

There is no real, plausible reason to assume that Kitchener and

Oswald "Fitz" Fitzgerald,

living together for nine years, were celibate. They lived as a couple in

dangerous times, not long after the 1895 trial of the dramatist Oscar Wilde

which led to his public humiliation, imprisonment and death in 1900.

Kitchener was credited in 1898 for winning the Battle of Omdurman and securing control of the Sudan for which he was made Lord Kitchener of Khartoum, becoming a qualifying peer and of mid-rank as an Earl. As Chief of Staff (1900–02) in the Second Boer War he played a key role in Lord Roberts' conquest of the Boer Republics, then succeeded Roberts as commander-in-chief – by which time Boer forces had taken to guerrilla fighting and British forces imprisoned Boer civilians in concentration camps. His term as Commander-in-Chief (1902–09) of the Army in India saw him quarrel with another eminent proconsul, the Viceroy Lord Curzon, who eventually resigned. Kitchener then returned to Egypt as British Agent and Consul-General (de facto administrator).

In 1914, at the start of the First World War, Kitchener became Secretary of State for War, a Cabinet Minister. One of the few to foresee a long war, lasting for at least three years, and with the authority to act effectively on that perception, he organised the largest volunteer army that Britain had seen, and oversaw a significant expansion of materials production to fight on the Western Front. Despite having warned of the difficulty of provisioning for a long war, he was blamed for the shortage of shells in the spring of 1915 – one of the events leading to the formation of a coalition government – and stripped of his control over munitions and strategy.

St. Paul's Cathedral, London

Westminster Abbey, London

On 5 June 1916, Kitchener was making his way to Russia to attend negotiations, on HMS Hampshire, when it struck a German mine 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west of the Orkney Islands, Scotland, and sank. Kitchener was among 737 who died.

Some biographers have concluded that Kitchener was a latent or active homosexual. Writers who make the case for his homosexuality include Montgomery Hyde,[147] Ronald Hyam,[148] Denis Judd[149] and Frank Richardson.[150] Philip Magnus hints at homosexuality, though Lady Winifred Renshaw said that Magnus later repudiated this belief.[[151]

The proponents of the case point to Kitchener's friend Captain Oswald Fitzgerald, his "constant and inseparable companion", whom he appointed his aide-de-camp. They remained close until they met a common death on their voyage to Russia.[147] From his time in Egypt in 1892, he gathered around him a cadre of eager young and unmarried officers nicknamed "Kitchener's band of boys". He also avoided interviews with women, took a great deal of interest in the Boy Scout movement, and decorated his rose garden with four pairs of sculptured bronze boys. According to Hyam, "there is no evidence that he ever loved a woman".[148]

‘Fitz’, a quiet, orderly man who was 25 years younger than Kitchener, provided the older man with companionship. Their shared interests included fine arts, and they became partners in East African estates and property enterprise. In 1916 ‘Fitz’ even shared Kitchener’s death.

In The Kitchener Enigma (1985), Trevor Royle describes ‘Fitz’ as Kitchener’s ‘constant companion and paladin who put his chief ’s interests above all others. Many resented the aura of quarantine “Fitz” brought to Kitchener’s entourage.’

In 1970 H. Montgomery Hyde mentioned Kitchener in The Other Love, his survey of homosexuality in Britain. He also drew upon Kitchener’s 1958 biographer, Philip Magnus to highlight the devotion ‘Fitz’ had for the older man: ‘their intimate association was happy and fortunate. Fitzgerald, like Kitchener, was a bachelor and celibate; he devoted the whole of the rest of his life exclusively to Kitchener.’

John Pollock, in his 1998 biography, Kitchener: The Road to Omdurman, felt it necessary to add an appendix entitled ‘Kitchener and Sex’. Pollock takes great pains to refute the claim that Kitchener was homosexual and criticises Frank Richardson, a retired medical major-general, for including Kitchener in his 1981 book Mars Without Venus: A Study of Some Homosexual Generals: ‘He suggested that Kitchener’s passion for porcelain and his love of flower arranging were symptoms of homosexuality. Porcelain is not the preserve of homosexual collectors.’

My published books:/p>