Queer Places:

3144 School St, St. Louis, MO 63106

2930 Locust St, St. Louis, MO 63103

2702 Lucas Ave, St. Louis, MO 63103

2839 Morgan St, St. Louis, MO 63102

1215 Dolman St, St. Louis, MO 63104

2930 Washington Blvd, St. Louis, MO 63103

3128 Laclede Ave, St. Louis, MO 63103

4904 Fountain Ave, St. Louis, MO 63113

5077 Page Blvd, St. Louis, MO 63113

4478 W Belle Pl, St. Louis, MO 63108

4406 W Belle Pl, St. Louis, MO 63108

5641 Cates Ave, St. Louis, MO 63112

11 5th Ave, New York, NY 10003

116 W 59th St, New York, NY 10019

12 W 69th St, New York, NY 10023

Hotel des Artistes, 1 W 67th St, New York, NY 10023, USA

27 W 67th St, New York, NY 10023

340 W 85th St, New York, NY 10024

1 W 64th St, New York, NY 10023

350 W 75th St, New York, NY 10023

260 W 72nd St, New York, NY 10023

New Mount Sinai Cemetery and Mausoleum

Affton, St. Louis County, Missouri, USA

Fannie

Hurst (October 19, 1885 – February 23, 1968)[1]

was an American

novelist

and short-story writer whose works were highly popular during the post-World

War I era. Her work combined sentimental, romantic themes with social

issues of the day, such as women's rights and race relations. She was one of

the most widely read female authors of the 20th century, and for a time in the

1920s she was one of the highest-paid American writers, along with

Booth Tarkington. Hurst also actively supported a number of social causes,

including feminism,

African American equality, and

New Deal

programs.[2]

She was a member of the Heterodoxy Club.

Fannie

Hurst (October 19, 1885 – February 23, 1968)[1]

was an American

novelist

and short-story writer whose works were highly popular during the post-World

War I era. Her work combined sentimental, romantic themes with social

issues of the day, such as women's rights and race relations. She was one of

the most widely read female authors of the 20th century, and for a time in the

1920s she was one of the highest-paid American writers, along with

Booth Tarkington. Hurst also actively supported a number of social causes,

including feminism,

African American equality, and

New Deal

programs.[2]

She was a member of the Heterodoxy Club.

Born into a comfortably middle class German-Jewish family in 1889, Hurst lived most of her young life in St. Louis and attended and graduated from Washington University in 1909. From 1885 to 1901 Gould's St. Louis Directory, shows residences for Samuel Hurst at the following addres.- 3144 School Street (1888-89); 2930 Locust (1890); 2702 Lucas (1891); 2839 Morgan (1892); 1215 Dolman (1893); 2930 Washington (1894); 3128 Laclede, the boarding house of Mrs. Parker L. Cleveland (1895); 4904 Fountain, a boarding house (1896); 5077 Page Blvd. (1897); 4478 West Belle Place, a boarding house (1898-99); and 4406 West Belle Place (1901-1906). The Hursts didn't move to the address at 5641 Cates Avenue until 1906, when Fannie was 21 and a sophomore in college.

At the age of 25, in 1910, Hurst moved to New York City under the auspices of attending an extension or graduate program at Columbia University. While there is no record of her ever actually attending any such program, what is well accounted for is Hurst’s sudden rise to prominence as a frequent contributor of fiction to popular magazines, eventually earning her the title of “world’s highest paid short-story writer”

At first Hurst lived in a narrow "hall room" within a mile of Columbia. From there she moved downtown, a fourth floor "slit of a room", where she spent three weeks. An introduction by her mother got her to see the director of the Three Arts Club, a women's residence for aspiring artists, actresses and musicians, at 340 West 85th Street. Fannie presented herself as actress and moved uptown. When there was no chance of fooling the Three Arts Club any longer, she spent a couple of months back in St. Louis, and then a brief time at Harperly Hall, the apartment building at the corner of 64th Street and Central Park West. By early January 1913 she moved to 350 West 75th Street and six months later she moved to 260 West 72nd Street, just off West End Avenue.

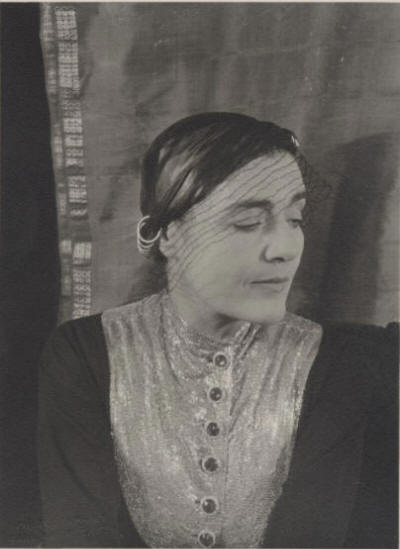

Fannie Hurst in 1932. Photograph by

Carl Van Vechten

Fannie Hurst in 1914

In 1914, the successful and financially independent young author rented the first of a series of Greenwich Village apartments, immersing herself in the Village’s cultural milieu. At first she moved to the Brevoort hotel, a place she described as "this old pension-like French hotel, much attmosphere, mostly garlic, soot red plush and Ritz-Carlton rates (By far the oldest and most fashionable hotel on lower Fifth Avenue, the Brevoort stood at the northeast corner of 8th Street for a century—from 1854 to 1954. In the 1920s its French-born owner Raymond Orteig offered a prize of $25,000 to the first pilot to fly non-stop from New York to Paris. On June 27, 1927 the prize was awarded at the Brevoort to Charles A. Lindbergh. The present apartment building at 11 Fifth Avenue takes its name from the hotel. The rock star Buddy Holly lived here in 1958.) By October 1914 Hurst rented a wonderful top-floor apartment on East 11th Street with fireplace, skylight, a 27 square-foor studio and three smaller chambers, kitchenette and bathroom. Hurst’s biographer Brooke Kroeger notes that the writer’s Greenwich Village years had a lasting impact, expanding both her social circle and her social conscious. Among Hurst’s new friends was Marie Jenney Howe, a trained (but not practicing) Unitarian minister and feminist activist. Howe had recently founded a radical feminist organization for “unorthodox women” known as Heterodoxy, which met for biweekly luncheons at Polly Halliday’s on MacDougal Street. Heterodoxy was a forum for “unorthodox” women (including many bisexuals and lesbians) to debate cultural, political, and sexual reforms deemed radical at the time. Hurst’s name was immediately added to this organization’s membership role, joining other feminist luminaries such as Alice Duer Miller, Crystal Eastman, and Charlotte “The Yellow Wallpaper” Perkins Gilman.

In 1915, Hurst secretly married Jacques S. Danielson, a Russian émigré pianist. Hurst kept her maiden name and the couple maintained separate residences and arranged to renew their marriage contract every five years, if they both agreed to do so. The revelation of the marriage in 1920 made national headlines, and The New York Times criticized the couple in an editorial for occupying two residences during a housing shortage. Hurst responded by saying that a married woman had the right to retain her own name, her own special life, and her personal liberty. Hurst and Danielson had no children, and remained married until Danielson's death in 1952. After his death, Hurst continued to write weekly letters to him for the next 16 years until she died, and regularly wore a calla lily, the first flower he had ever sent her.

By 1916 she moved out of the Village Apartment and returned to the Upper West Side, living for several months at 116 West 59th Street and renting a studio at Carnegie Hall before moving on to a brand new skylit building of studio apartments at 12 West 69th Street in December 1916, into a "distractingly attractive" little apartment with "monastery doors, old rugs, steps up and down, Gothic windows and a scatter-brained puppy to amuse her." It would be home for the next seven years. Only two stories high, the structure was built low to keep from blocking the light of the apartment house next door at 88 Central Park West. The 1917 city directory lists Jacques Danielson with an apartment at the same building address. For years after they moved out, Hurst thought the building should have a plaque that read, "Happiness Dwelt Here."

During the 1920s and 1930s, while she was married to Danielson, Hurst also had a long affair with Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson.[19][20][21] They often met at Romany Marie's café in Greenwich Village when Stefansson was in town. According to Stefansson, at one point Hurst considered divorcing Danielson in order to marry him, but decided against it. Hurst and Stefansson ended their relationship in 1939.

Although her novels, including Lummox (1923), Back Street (1931), and Imitation of Life (1933), lost popularity over time and were mostly out-of-print as of the 2000s, they were bestsellers when first published and were translated into many languages. She also published over 300 short stories during her lifetime. Hurst is known for the film adaptations of her works, including Imitation of Life (1934), starring Claudette Colbert, Louise Beavers, Fredi Washington, and Warren William; Imitation of Life (1959), starring Lana Turner; Humoresque (1946), starring Joan Crawford; and Young at Heart (1954), starring Frank Sinatra.

In 1925 Hurst moved to a studio building at 27 West 67th Street. This is where Hurston moved as live-in secretary. Zora Neale Hurston attended Barnard College in 1925 with assistance from her literary mentor Fannie Hurst and Barnard College co-founder Annie Nathan Meyer.[4] Hurst's novel, Imitation of Life (1933), was also hugely popular, and is now considered her best known and most famous novel. It told the story of two single mothers, one white and one African American, who become partners in a successful waffle and restaurant business (modeled after Quaker Oats Company's "Aunt Jemima" pancake mix) and have conflicts with their teenage daughters. Hurst's inspiration for the book was her own friendship with Hurston. Hurston, who served as Hurst’s chauffeur, secretary, and confidante while studying anthropology at Barnard, classed Hurst with the “Negrotarians,” a mildly derisive term for whites dedicated to Negro uplift.

Hurst was friends with many leading figures of the Harlem Renaissance, including Carl Van Vechten.[13]

Overweight as a child and young woman, Hurst had a lifelong concern about her weight. She was known in literary circles as an avid dieter and published an autobiographical memoir about her dieting, No Food With My Meals, in 1935.

In September 1937 Hurst and her husband moved into a grand, new white elephant of a triplex at the Hotel des Artistes, at 1 West 67th Street, off Central Park West. 10.000 square feet on the top three floors. The rent was in the neighborhood of 5.000 dollars a month.

She campaigned for a married woman's right to retain her maiden name, fought racial discrimination alongside the Urban League, and raised money for refugees of Nazi Germany. A talk show she hosted in the late 1950s broke new ground by featuring forthright discussions of homosexuality, and Hurst was among the first public figures to champion gay rights. She gave a speech in support of gay rights at the Mattachine Society’s fifth annual convention in New York in August 1958, eleven years before the Stonewall Riots galvanized a larger gay rights movement.

According to Ariel Schudson: “Her contribution to the moving image media world was not solely made through the adaptation of literary works. Beginning in 1958, Hurst hosted a talk show called Showcase that featured public affairs panels and social issue-based interviews. Showcase was one of the first television forums in which the gay and lesbian community was invited to speak on their own behalf instead of being given the third degree or being treated as though they were a science project. Most previous television appearances of homosexual men or women featured them being studied or questioned as though they existed within a fishbowl or were a group to be “dealt with” by a panel of specialists. Hurst’s breakthrough show was not as popular as one might have hoped. While Fannie Hurst’s support of the gay and lesbian community was unfailing (and had been so for years), the television stations were not all game for this content. While her fame certainly had some cache, it didn’t outweigh rampant homophobia. Showcase was cancelled several times by more than one station, finally ending for good after a year.

As Steven Capsuto writes, 'Hurst had contentious disagreements with station managers over her insistence on presenting panel discussions about homosexuality, and these broadcasts may have contributed to the cancellations. When the second station, New York’s Channel 13, axed the show definitively in 1959, Hurst had begun devoting one show a week to the subject of homosexuality. The final Showcase broadcast focused on same-sex desire among teenagers.’”

In 1958, Hurst published her autobiography, Anatomy of Me, which described many of her friendships and encounters with famous people of the era such as Theodore Dreiser and Eleanor Roosevelt.

At the time of her death she was living at the Hotel des Artistes, at 1 West 67th Street. Hurst died on February 23, 1968, at her apartment in New York City, after a brief illness.[1] A few weeks before she died, she sent her publishers two new novels, one untitled and the other entitled Lonely is Only a Word. Her obituary made the front page of The New York Times.

My published books: