Partner Gean Harwood

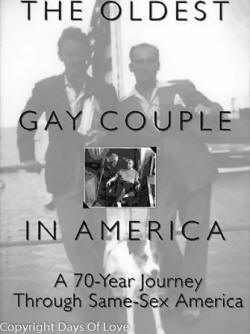

The lives of Bruhs Mero (February 15, 1911 - August 10, 1995) and L. Eugene "Gean" Harwood (1909-2006) are recounted in the book by Harwood, ''The Oldest Gay Couple in America: A Seventy-Year Journey Through Same-Sex America''.

The lives of Bruhs Mero (February 15, 1911 - August 10, 1995) and L. Eugene "Gean" Harwood (1909-2006) are recounted in the book by Harwood, ''The Oldest Gay Couple in America: A Seventy-Year Journey Through Same-Sex America''.

Bruhs Mero and Gean Harwood are profiled in ''Family: a portrait of gay and lesbian America'', by Nancy Andrews (1994) and in ''Living happily ever after: couples talk about lasting love'',

by Laurie Wagner, Stephanie Rausser, and David Collier (1996).

L. Eugene "Gean" Harwood was born in Auburn, New York, where he first studied music.

Bruhs Mero and Gean Harwood were partners in life and music. They wrote their first composition, "Come and Take My Hand", in 1933. The text was a poem by Mero, who was forced to live alone in Florida for a period due to the lack of jobs in New York City; the loneliness pushed him to wrote the poem and he sent it to Harwood who put it in music. More than 50 other songs would follow.

Harwood worked for Paramount Pictures in New York City for twenty years; he made transportation arrangements for actors and executives. In this role, he had the chance to meet Cary Grant and Randolph Scott and to his impression, it was clear they were more than just friends.[1] Harwood later became administrative assistant for the New York City's building department, retiring in 1971.

Bruhs at first worked in advertising and later became a professional dancer, working on and off Broadway. He also taught dance and coreographed modern dance performances using the music of Harwood. In 1939 Mero and Harwood opened the Dance Gallery. In 1943 Mero had his first solo performance at Broadway with Harwood playing piano, but an hearth attack interrupted his dance career. After that Mero worked as a writer for a trade publication.

by Nancy Andrews

On June 30, 1985, during the New York Pride, Gean Harwood and Bruhs Mero were ailed as "Grand Marshals".[2]

After Mero's death in 1995, Harwood remained active: he played the piano into his 90s and was active in the Services & Advocacy for GLBT Elders (SAGE).[3]

The unwelcomed climate of Upstate New York pushed Harwood to move to New York City where he met Mero in 1929. They first kissed on New Year's Eve 1929 and remained together for 66 years, until Mero's death in 1995. They lived in an Lower East Side studio apartment. In 1991 Mero moved to a nursing home, but Harwood continued to visit him constantly, even if Mero, affected by Alzheimer’s disease, did not recognized him anymore.[4]

Harwood never came out to his family, and Mero did it only in 1979. They kept their relationship private until 1985 when they made coming out on ''The Phil Donahue Show''.[5] [6]

Bruhs Mero died from Alzheimer’s disease on August 10, 1995. Harwood died in 2006.[7]

Bruhs Mero and Gean Harwood are profiled in ''Silent Pioneers'', a 1984 documentary by Lucy Winter, Harvey Marks, Paula de Koenigsberg, and Patricia G. Snyder,[8] and ''For Better or for Worse'', the musical chronicling their love affair, was an Academy Award-nomination in 1993.

A second musical, ''Sixty Years with Bruhs & Gean'', written by Tom Wilson Weinberg and directed by Jim Vivyan, was produced in 2008. The musical was commissioned by the New York City Gay Men's Chorus and originally performed at Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center and featured on "In The Life" on PBS.[9]

GEAN HARWOOD AND BRUHS MERO: Gean Harwood and Bruhs (pronounced Bruce) Mero first kissed on New Year's Eve in 1929. They have been together ever since, for sixty-three years. Gean, eighty-four, worked for Paramount Pictures and later for New York City's building department, retiring from the department in 1971. Bruhs, eighty-two, first worked in advertising and then became a professional dancer, working on and off Broadway. He and Gean wrote songs together and opened the Dance Gallery in New York in 1939. To make ends meet, they lived in the studio where Bruhs taught dance and held original modern-dance performances using music composed by Gean. In 1943, shortly after Bruhs's first solo Broadway appearance, in which Gean accompanied him on the piano, Bruhs suffered a heart attack. His dance career abruptly ended. After a long recovery, he worked as a writer for a trade publication. In the mid-1980s, Bruhs began to show signs of Alzheimer's disease. By 1991, he required around-the-clock supervision and was moved to a nursing home. Gean still lives in the Lower East Side studio apartment the two shared for thirty years. Gean takes an hour's bus ride through the city to the nursing home just four blocks northwest of Central Park. During a visit, Bruhs gives little reaction to Gean. Gean kisses him on the cheek, then, clasping Bruhs's hand, leads him to the recreation room. There a lone woman sits inches away from a loud television. Gean begins to play the piano, battling the sound of the TV. The piano wins, and gradually patients and staff drift in to listen to Gean. One woman sings, while another requests show tunes. Bruhs sits in a chair by Gean's side. Gradually he begins to tap his foot to the music and even smile. Gean plays songs the two composed, periodically smiling at Bruhs. But Bruhs's vacant stare does not return the warmth. He does not utter a word, let alone sing any of the more than thirty songs he wrote with Gean. The two were photographed as Gean said good-bye to Bruhs in his room at the nursing home. Gean: Very frequently, gay people meet in bars or on a park bench or something, but our meeting was very legitimate. We were introduced by mutual friends. It was near the end of 1929. I was very attracted to him but I was warned that even though he was circulating in some gay company, he was very seriously committed to a young woman. They were actually engaged, and so I decided I should really cool it and not indicate my feelings. Then a very dramatic thing happened with my apartment. The landlord found out that one of my roommates was gay. He knocked on the door and said, "I want you all out of here within forty-eight hours." So I said, "We have a lease." He said, "Well, your lease is canceled; I am not renting any of my apartments to fags." So this was my first brush with discrimination, and I was twenty years old. I called Bruhs, because I was new in town and I didn't know many other people. And he needed a place then also. That's how we started living together. I was very, very much attracted to him, but I had declared him off-limits because of his arrangement with the girl. I didn't want to do anything to interfere with that, but we finally became much closer. It must have been fate that threw us together. Bruhs didn't have a date that New Year's and neither did I. Our building was full of musicians, and they used to have wonderful parties. They had a big one on New Year's Eve, and we were both invited. We went and had quite a little bit to drink. After the thing was all over we went back upstairs together, and I guess the liquor and all had reduced the inhibitions we both felt. That was really the first time that we came together. The chemistry was right, and it just went on from there and developed. There didn't seem to be any recriminations on Bruhs's part. He seemed to be very content that this was really what he wanted, that he had really found himself. I think he was very reluctant to commit to anyone, and it wasn't until he met me and spent some time with me, living under the same roof, that he got to feel that this was something that he could commit to. He finally broke off the engagement with the girl and decided to stay with me. We lived very closeted lives, and I was never out to my family. But after all, with two men who never married and had been together all these years, they had to realize that something was going on. This wasn't a "normal" arrangement. Bruhs finally came out to his family around 1979. I thought to myself afterwards, "How silly. How silly I have been all these years to be hiding. We have nothing to be ashamed of." I feel very grateful that we did share all those wonderful years. During the Depression in '33, Bruhs lost his job here, so he worked with his brother temporarily in Florida. He was very lonely there. He finally wrote a poem about it. I thought it was the basis for a song, and when he sent me a copy of it, I set it to music. This was our very first song. It's called "Come and Take My Hand." The songs were a joint creation for us. Sometimes Bruhs wrote the words first and I put music to it. Sometimes I had to change the meter a little bit, but not enough to detract from the poem. Other times, I composed something in the way of music and he put words to it. Sometimes it required sitting side by side and doing the thing. We wrote our last song together in 1982. The title was "I'll Never Say Good-bye." I couldn't play that for the longest time. It was too hard, remembering Bruhs how he used to be. When I had Bruhs at home, I made a point to play one hour a day because that's how we could communicate. When he sang he was himself. At one time he knew all the words, he could do them by heart. Then we used sheets. Now he doesn't sing at all. The last few months that I spent with Bruhs were so, so tremendously tense. I was actu¬ ally very insecure. I felt my own safety was being threatened because he was so unbal¬ anced. Even though I was totally reluctant about giving up on him and putting him in an institution, it finally got to the point where this was a twenty-four-hour ordeal for me. Some of the people at the nursing home understand that we were life partners, but not everyone does. I go to visit, but it isn't very rewarding for either one of us at this stage of the game. Bruhs vaguely recognizes the fact that I am somebody he should know, but he's not able to sort it out—who I am and why I am there. There is a certain amount of frustration on his part. In the early days when he was there, he used to say to me, "There's something wrong here. What is wrong?" He was very troubled for a long time. Now he doesn't say any of those things anymore. He would take hold of my hand and say, "I only want to be with you." That was hard on me, and now the indifference he has is equally difficult for me to handle. I guess there's no way out of that; it is the nature of the disease. With Alzheimer's, in some ways it's more difficult for the person giving the care than the one receiving it. The relationship was something that meant a great deal to both of us. We really felt that we belonged together. There were times in our existence when there were some very strong pulls away from each other, but there was a continuity there that neither one of us could ignore, and somehow we seemed to be destined to be together. It's very hard to put into words what that span of time really meant. I find it at this stage practically impossible to describe.

My published books: