Partner Nancy Earl

Queer Places:

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Wheatley High School, 4801 Providence St, Houston, TX 77020, Stati Uniti

Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, Stati Uniti

Texas Southern University, 3100 Cleburne St, Houston, TX 77004, Stati Uniti

Texas State Cemetery, 909 Navasota St, Austin, TX 78702, Stati Uniti

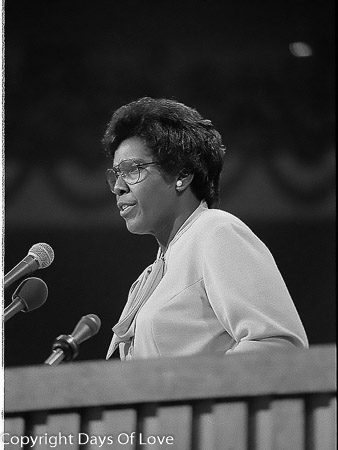

Barbara Charline Jordan (February 21, 1936 – January 17, 1996) was an

American lawyer, educator[1] and politician who was a leader

of the Civil Rights Movement. A Democrat, she was the first African American elected to the Texas

Senate after Reconstruction, the

first Southern African-American woman elected to the

United States House of Representatives.[2]

She was best known for her eloquent opening statement[3] at the House

Judiciary Committee hearings during the impeachment process against Richard

Nixon, and as the first African-American woman to deliver a keynote address at

a Democratic National Convention. She received the Presidential Medal of

Freedom, among numerous other honors. She was a member of the Peabody

Awards Board of Jurors from 1978 to 1980.[4] She

was the first African-American woman to be buried in the Texas State

Cemetery.[5][6]

Barbara Charline Jordan (February 21, 1936 – January 17, 1996) was an

American lawyer, educator[1] and politician who was a leader

of the Civil Rights Movement. A Democrat, she was the first African American elected to the Texas

Senate after Reconstruction, the

first Southern African-American woman elected to the

United States House of Representatives.[2]

She was best known for her eloquent opening statement[3] at the House

Judiciary Committee hearings during the impeachment process against Richard

Nixon, and as the first African-American woman to deliver a keynote address at

a Democratic National Convention. She received the Presidential Medal of

Freedom, among numerous other honors. She was a member of the Peabody

Awards Board of Jurors from 1978 to 1980.[4] She

was the first African-American woman to be buried in the Texas State

Cemetery.[5][6]

Barbara Charline Jordan was born in Houston, Texas's Fourth Ward. Jordan's childhood was centered on

church life. Her mother was Arlyne Patten Jordan, a teacher in the church,[7] and her father was

Benjamin Jordan, a Baptist preacher. Barbara Jordan was the youngest of 3

children, with siblings Rosemary Jordan McGowan and Bennie

Jordan Creswell (d. 2000). Jordan attended Roberson Elementary School. She graduated from Phillis Wheatley High School in 1952 with honors.[8]

Jordan credited a speech she heard in her high school years by Edith S.

Sampson with inspiring her to become a lawyer.[9]

Because of segregation, she could not attend The

University of Texas at Austin and instead chose Texas Southern University,

an historically-black

institution, majoring in political science and history. At Texas Southern

University, Jordan was a national champion debater, defeating opponents from

Yale and Brown and tying Harvard University. She

graduated ''magna cum laude'' in 1956. At Texas Southern University, she

pledged Delta Sigma Theta sorority. She attended Boston University School

of Law, graduating in 1959.

Jordan taught political science at Tuskegee Institute in

Alabama for a year. In 1960, she returned to Houston, passed the bar and started a private law practice.

Jordan campaigned unsuccessfully

in 1962 and 1964 for the Texas House of Representatives.[10] She won a seat in the Texas Senate in

1966, becoming the first African-American state senator since 1883 and the first

black woman to serve in that body. Re-elected to a full

term in the Texas Senate in 1968, she served until 1972. She was the first

African-American female to serve as president ''pro tem'' of the state

senate and served one day, June 10, 1972, as acting governor of Texas. To date Jordan is the only

African-American woman to serve as governor of a state (excluding lieutenant

governors).[11] During her time in the Texas

Legislature, Jordan sponsored or cosponsored some 70 bills.

In 1972, she was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, the first

woman in her own right to represent Texas in the House. She received extensive

support from former President Lyndon B.

Johnson, who helped her secure a position on the House Judiciary Committee. In 1974, she made an

influential televised speech before the House Judiciary Committee supporting the

impeachment of President Richard Nixon, Johnson's successor as

President.[12] In 1975, she was appointed by

Carl Albert, then Speaker of the United States House of Representatives,

to the Democratic Steering and Policy Committee.

In 1972, she was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, the first

woman in her own right to represent Texas in the House. She received extensive

support from former President Lyndon B.

Johnson, who helped her secure a position on the House Judiciary Committee. In 1974, she made an

influential televised speech before the House Judiciary Committee supporting the

impeachment of President Richard Nixon, Johnson's successor as

President.[12] In 1975, she was appointed by

Carl Albert, then Speaker of the United States House of Representatives,

to the Democratic Steering and Policy Committee.

In 1976, Jordan,

mentioned as a possible running mate to Jimmy Carter of Georgia, became instead the first African-American

woman to deliver a keynote address at the Democratic National Convention. Despite not

being a candidate, Jordan received one delegate vote (0.03%) for President at

the Convention.[13]

Jordan retired from politics in 1979 and became an

adjunct professor teaching ethics at the University of Texas at Austin

Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs. She was again a keynote speaker at

the Democratic National Convention in 1992.

In 1994 and until her death

in 1996, Jordan chaired the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform, which set of

recommendations for comprehensive immigration reform.[14]

In 1994, Clinton

awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom and The NAACP presented her with

the Spingarn Medal. She was honored many times and was given over 20 honorary

degrees from institutions across the country, including Harvard and Princeton,

and was elected to the Texas and National Women's Halls of Fame.

On July 25, 1974, Texas Representative Barbara Jordan delivered a 15-minute televised

speech in front of the members of the U.S. House Judiciary Committee.[15] She presented an opening speech during the

hearings that were part of the impeachment process against Richard

Nixon. This speech is thought to be one of the best

speeches of the 20th

century.[16] Throughout her speech, Jordan strongly stood by the

Constitution of the United States of America. She defended the checks and

balances system, which was set in place to inhibit any politician from abusing

their power. Jordan never flat out said that she wanted

Nixon impeached, but rather subtly and cleverly implied her thoughts.[17] She

simply stated facts that proved Nixon to be untrustworthy and heavily involved

in illegal situations, and quoted the drafters of the

Constitution in order to argue that actions like Nixon's during the scandal

corresponded with their understanding of impeachable offenses. She protested that the Watergate

scandal will forever ruin the trust American citizens have for their

government. One of the reasons Nixon resigned over the

Watergate scandal was because of this speech. This powerful and influential

statement earned Jordan national praise for her rhetoric, morals, and wisdom.

Jordan supported the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, legislation

that required banks to lend and make services available to underserved poor and

minority communities. She supported the renewal of the Voting Rights Act of

1965 and expansion of that act to cover language minorities; this extended

protection to Hispanics in Texas and was opposed by Texas Governor Dolph

Briscoe and Secretary of State Mark White. She also authored an act that

ended federal authorization of price fixing by manufacturers. During Jordan's

tenure as a Congresswoman she sponsored or cosponsored over 300 bills or

resolutions, several of which are still in effect today as law.

Jordan's companion of approximately twenty years[18] was Nancy

Earl,[19] an educational psychologist, whom she

met on a camping trip in the late 1960s. Jordan's sexual orientation has never been determined, but some

sources list her as a lesbian.[20] She would have

been the first lesbian known to have been elected to the United States

Congress. Earl was an occasional speech writer for Jordan, and later was a

caregiver when Jordan began to suffer from multiple sclerosis in 1973. In the

KUT radio documentary ''Rediscovering Barbara Jordan'', President Bill Clinton said that he wanted to nominate

Jordan for the United States Supreme Court, but by the time he could do so,

Jordan's health problems prevented him from nominating

her.[21] Jordan later also suffered from leukemia.[22]

In 1988, Jordan nearly drowned in her backyard swimming pool while doing

physical therapy, but she was saved by Earl who found her floating in the pool

and revived her.[23]

Jordan died at the age of 59 due to complications from pneumonia on January

17, 1996, in Austin, Texas.[24]

My published books: