Queer Places:

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Peabody Essex Museum, 161 Essex St, Salem, MA 01970

Burnside, Prides Crossing, Beverly, MA 01915

Mount Auburn Cemetery

Cambridge, Middlesex County, Massachusetts, USA

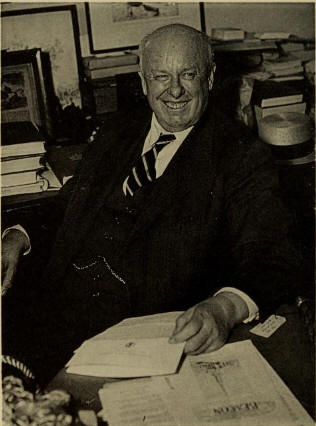

Augustus

"Gus" Peabody Loring, Jr. (April 16, 1885 - October 1, 1951) was a member of the

Horace Walpole Society, elected in1946.

Augustus

"Gus" Peabody Loring, Jr. (April 16, 1885 - October 1, 1951) was a member of the

Horace Walpole Society, elected in1946.

On the evening of 14 October 1949 delegates from more than seventy institutions, museums and learned societies met in East India Marine Hall. Settling their knees under a long dining table decorated with ship models, birds of paradise and East Indian booty, they made ready to celebrate the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the foundation of the museum of the Salem East India Marine Society. At the centre, elegantly flanked by a pair of great Chinese porcelain soup tureens in the form of geese, given to the East India Marine Society in 1803, sat Augustus Peabody Loring, Jr., President of the Peabody Museum of Salem. The rum punch he dispensed had been made by his own hands from a recipe brought from the West Indies by his great-great-grandfather, Captain Joseph Peabody (1757-1844). At the end of dinner, when the glasses had been replenished, Gus, as presiding officer, rose and proposed the toast "The Mariners of Essex— and their tributes in peace and war, to the glory of their country," originally offered by President John Quincy Adams at the dedication of the hall one hundred and twenty-four years earlier. Meanwhile a rustic orchestra sawed out Hail Columbia. Although the toasts on the later occasion were prudently reduced from fifty-one to twelve in number, the pattern of the evening closely followed that of the early dinners of the East India Marine Society, and certainly the presiding officer strikingly resembled an eighteenth-century gen- tleman who had temporarily mislaid his wig! The following day, when Samuel Eliot Morison, the delegate from Harvard College, offered the visitors' thanks for the entertainment provided, he lamented, with feeling, that the delegates had been deprived of the pleasure of seeing Loring dressed in the costume of a Chinese mandarin, reclining in the Indian palanquin that occupied so prominent a place in the East India Marine Society processions, borne upon the shoulders of the director and assistant director of the Museum and the brothers James Duncan and Stephen W. Phillips. The picture conjured up made the audience laugh till they cried, but the suggestion had this appropriateness—even without a procession the President was the centre and heart of the entire celebration.

By temperament, historical interest, inheritance and business acumen Gus Loring was uniquely fitted to guide the affairs of this ancient Essex County institution concerned with the sea and the distant lands visited by sea-faring men.

He was, first of all, a skillful sailor with a competence in seamanship that would have enabled him to be spectacular, if it had not always been repugnant to him to act solely for the sake of making an effect. As a boy at Prides Crossing, where his great-grandfather and grandfather had been among the earliest summer residents, he had mastered the ways of boats. In fact, before he was in his teens, Gus, with a boy of similar age, had put to sea one day and— without having warned their families of any such intention— cruised to the eastward until they reached Pemaquid! This was the beginning of a lifelong pleasure. For over forty years he regularly ranged the Maine coast, and in the month spent afloat each summer renewed his strength for the varied and onerous occupations that filled every waking hour of the remainder of the year. He chose his boats rather as he chose his clothes, for quality, serviceability and comfort. He cruised comfortably, too, and non-competitively, without preconceived ideas of course or speed, planning from day to day as wind and weather indicated. By the end of the afternoon he would be in a sheltered anchorage, happily at work preparing a monumental dinner that would be preceded by a swizzle and accompanied by a bottle of wine. The very magnitude of his person suggested the pleasures of the table, although anyone who saw him rowing an overloaded boat in a rough sea knew that much of it was muscle. Not only did he know and like good food; he could cook it also. His knack with pressure cookers allowed him to produce in a tiny galley, with neat and rapid dexterity, a dinner that would have done credit to a French cook. He rarely went ashore, except for ice and provisions or to see an old friend, but when he did he knew how to behave in Maine. His father had owned much of Bartlett's Island in Blue Hill Bay and the Lorings understood Maine people.

The sea was in Gus Loring's blood. His great-great-grandfather, Joseph Peabody, had gone to sea as a boy, and on his death in 1844 as the richest merchant of the day in Salem, had built and owned eighty-three ships that he freighted himself. His great-grandfather, John Lowell Gardner, was a Boston ship-owner and merchant in the East India and Russia trades. Another great-great-grand-father, Caleb Loring, had been a founder of the Plymouth Cordage Company in 1824, and his grandfather and father were successively its presidents, from 1890 to 1936. Gus himself became a director of that company in 1913 and its president in 1939. In 1941 upon retiring as president, he became the first chairman of the board of directors. Neither at Plymouth, nor anywhere else, was he shackled by the past. Although a firm upholder of traditions, when they were good and still useful, he was constantly looking ahead and seeing around corners. In 1920, at his insistence, the Plymouth Cordage Company established the first laboratory in the cordage industry; the experiments with synthetic fibres that began about 1936 proved their worth when the great fibre-producing areas were cut off in World War II. Plymouth's nylon rope— used extensively by the United States Navy and Air Corps— gave him particular satisfaction.

In 1911 Gus Loring married Rosamond Bowditch, a great-granddaughter of Nathaniel Bowditch. The following year he entered the business of managing trusts and estates with his father-in-law, Alfred Bowditch. In that capacity he was responsible for the management of innumerable personal and business properties, continuing with probity and brilliance the tradition of the private trustee that had begun in Boston more than a century earlier with Nathaniel Bowditch. Outside his office he participated in many business enterprises, being a director— among other companies — of the Boston and Maine Railroad, Houghton Mifflin Company, Massachusetts Hospital Life Insurance Company, New England Trust Company, and, as far away as Texas, president and director of the Galveston-Houston Company.

In the 1930s Gus Loring began to take an active role in historical and antiquarian matters, and usually, soon after becoming a member of an organization, he found himself doing most of its hard work. In 1931 he was elected a resident member of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, in 1934 its recording secretary and in 1946 its president. In 1932 he joined the Club of Odd Volumes, became its clerk in 1933 and its president in 1942. In 1936 he was elected to the American Antiquarian Society, and from 1941 was a valued member of its council. Having become a resident member of the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1937, he served as its treasurer— and a particularly thankless job it was— from 1943 onward. So, in a familiar pattern, it was in no way surprising that, having been elected a trustee of the Peabody Museum of Salem in 1939, he was the obvious person to become its president in 1942. Many Boston institutions work together harmoniously, with singularly little time wasted in lengthy committee meetings, because in them the same people do business with each other in different capacities, but Gus Loring was the "puller together" extraordinary. It would be a considerable undertaking to attempt to list his activities, but it should be noted that in 1946 he became vice-president of the Boston Athenaeum and in 1951 president of the Bostonian Society. One might well consider whether any other member of the Somerset, Tavern and Union Clubs also belonged to the Masons, Elks, Odd Fellows and Grange, or whether another Boston corporation executive also was a member of the Fabian Society! In the breadth of his acquaintance and sympathies lay the secret of his usefulness to all of these groups. He had packed an extraordinary number of experiences into his years.

As a not overly promising Harvard undergraduate in the class of 1908, he had surprised his professors by running for the Beverly city council, and getting elected, defeating the senior local politician in the process. During his first trip abroad, he and Starling Burgess, with whom he was travelling, had been summoned by King Edward VII to a luncheon a trots at the Royal Yacht Squadron at Cowes. He flew with Burgess in the early days of aviation. Although his wife prudently made him quit flying when they were married, he hung onto a steamboat engineer's license for some years. Strawberry Hill imprints always attracted him, and he collected Rowlandson and Gillray with zest. His knowledge of wine was encyclopedic; so too was his knowledge of and sympathy for people.

As he lumbered down the street— pockets bulging with papers and carrying a great leather bag that might contain anything under the sun from incunabula to fish, from plumber's tools to Peabody Punch— judges and police officers, lawyers and cab drivers, were equally delighted to see him. He accomplished almost as much business on the sidewalk as an ancient Athenian might have in the market place. To his office at 35 Congress Street— crowded with old prints of Boston, samples of rope, an incredible clutter of papers, and usually a few rare books that he had ordered as a surprise addition to his wife's collection— came the business and troubles of a great variety of institutions and individuals. He had a sympathetic ear for all, and the ability to seem unhurried, no matter how pressed he might be. He accomplished more than most men, partly because he picked his helpers skillfully and trusted them fully, but mostly because he thought faster and more incisively. Gus II Loring's physical appearance and the difficulty with which he sometimes found words had less than no relation to the subtlety of his mind. If provided with a red coat and a wig he would have made a convincing eighteenth-century portrait. When digging in his garden, running a clambake, or climbing over his boat he more than occasionally suggested Atlas, Silenus or Father Neptune. His realistic appraisal of his own beauty is shown by his delight in recalling that when a bee stung him on the end of the nose he reflected that if he could only keep the swelling permanently he might make a fortune as Cyrano on the vaudeville stage! Time and again he might come into a meeting, and when some controversial matter was leading to wordy discus- sion, fold his hands over his stomach and go to sleep. But at the crucial moment he would stir, and suddenly introduce an apparently innocent and simple remark that solved the problem, frequently not only to the advantage of that meeting but of other institutions as well. When something needed to be done he had uncanny skill in suggesting some- one—often known only to himself— who could not only do it well but would enjoy doing it. Thus he broadened the horizons of many groups and furthered the happiness of many individuals. He was generous in both great and small matters. Many a New Englander will be posthumous- ly generous on a large scale, but uncommonly mean where small sums of money are concerned. Gus made up for these by his ready perception of what was needed to oil the machinery of human relations. He made large gifts, but he also made an extraordinary number of small ones, so promptly and unhesitatingly that their value was trebled.

At the Peabody Museum of Salem his first accomlishment was restoring to its original appearance East India Marine Hall, built in 1825. This magnificent room, one hundred by thirty-five feet in size, had been sadly defaced in 1867, when it was, in a period of zoological enthusiasm, rammed full of exhibition cases and galleries that entirely destroyed its architectural quality. Under Gus Loring's urging, the late Thomas Barbour, a trustee from 1940 to 1946, undertook the Herculean task of separating rubbish from valuable specimens, installing the latter elsewhere, and clearing the hall so that it might be restored. Its rededication on 4 November 1943 for the exhibition of objects pertaining to maritime history marked both the resurrec- tion of one of the noblest rooms in New England and a milestone in the Museum's progress.

Equally valuable for the future of the institution was the painstaking thought, based upon wide experience, that he gave to the Museum's investments and business affairs. Although the casual observer might have expected the bearer of so many responsibilities to confine himself to at- tendance at stated meetings, there was nothing perfunc- tory about Gus Loring's manner of discharging his duties. On the contrary he was constantly in and out of the Mu- seum, bubbling with ideas and friendly assistance; and, in- cidentally but characteristically, through serving on the council of the Essex Institute he was able to strengthen the ties between two neighboring institutions.

Gus Loring was generous to the Museum both in gifts of objects and of funds, but perhaps his greatest service was in bringing the institution into a more intimate relation with the community by enlarging its parish boundaries to coincide with the breadth of his own enthusiasms and acquaintance. It was his idea to establish the Friends and Fellows of the Peabody Museum in the spring of 1951, and the gratifying response to the invitations to join these groups is evidence of the manner in which he and the Mu- seum had become identified with one another. Without disrespect to his warmth of feeling and willingness to help other institutions, it seemed clear to his friends that the Peabody Museum of Salem and the Club of Odd Volumes were the closest to his heart and the places where he was most at home.

He did much to encourage and assist the Museum staff, and from 1942 his wife, as honorary curator of exhibi- tions, quietly and unerringly filled the place of members absent on wartime service. Her election as a trustee in 1946, in recognition of what she had already done for the Museum, gave him singular pleasure.

Rose Loring was a unique complement to Gus. They had the same warmth and generosity of spirit, the same catholic friendliness, and they always laughed at the same things. I can never think of her without recalling Anne Bradstreet's lines "To my dear and loving husband":

If ever two were one, then surely we.

If ever man were lov'd by wife, then thee;

If ever wife was happy in a man,

Compare with me ye women if you can.

She was not only the selflessly loyal wife, the energetic, humorous and sympathetic mother of a numerous family, but quite independently a highly successful working crafts- man, designing and producing marbled and paste decorat- ed book papers with professional competence. In this same field she enjoyed a unique reputation as a collector and scholar, and Gus was always deathly proud of her accom- plishments. In the great house at 2 Gloucester Street, Bos- ton, and at Prides Crossing she presided with apparently effortless skill, abetting Gus's instinct for abundant hospi- tality. People streamed in and out of both houses; old friends were greeted with delight, and strangers rapidly became friends. For good company, talk, food and drink there was nothing like the Loring houses, but then there has never been anything quite like their owners. Then on 17 September 1950, Rose died. Gus resumed his customary duties without faltering, but one could not help remem- bering the word of the Lord to the prophet Ezekiel:

Behold, I take away from thee the desire of thine eyes with a stroke; yet neither shalt thou mourn or weep, neither shall thy tears run down. For- bear to cry, make no mourning for the dead. . . . So spake I unto the people in the morning; and at even my wife died; and I did in the morning as I was commanded.

In January 1951 an exhibition of Rose's decorated book papers at the Athenaeum was arranged. Gus brought a group of her tools, and it was touching to see how completely he remembered the use of each one and how precisely he knew the technique of her craft. In late March, on return- ing from his annual trip to Texas, he fell into the hands of i5 the doctors for a brain operation. After long weeks in the Phillips House, outside which the pile drivers were ham- mering on a new highway, he was able to go home to Prides late in June. There with the sea, and the sight of his boat, surrounded by children and grandchildren, he passed a relatively happy July and August. Friends came to see him; he talked of the future, and one day toward the close of this Indian summer of his life he drove to Salem to see the improvements that Mrs. Crowninshield was making in the exhibition rooms at the Museum. But his illness was too devastating even for his rugged strength to overcome, and on 1 October 1951 he died.

My published books: