Queer Places:

Housman’s & The Clock House, Bournheath, Bromsgrove B61 9HY, UK

Perry Hall, Kidderminster Rd, Bromsgrove B61 7JZ, UK

Bromsgrove School, Worcester Rd, Bromsgrove B61 7DU, UK

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

82 Talbot Rd, London W2, UK

15 Northumberland Pl, London W2, UK

39 Northumberland Pl, London W2 5AS, UK

Byron Cottage, 17 North Rd, Highgate, London N6, UK

Westminster Abbey, 20 Deans Yd, Westminster, London SW1P 3PA, UK

St Laurence, Ludlow SY8, UK

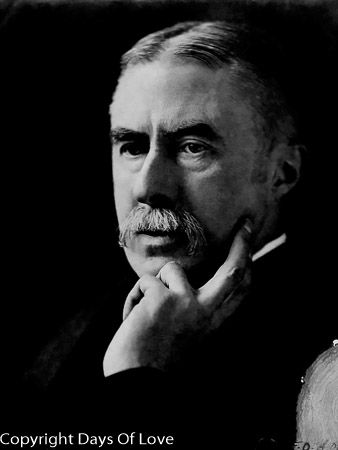

Alfred

Edward Housman (26 March 1859 – 30 April 1936), usually known as A. E. Housman, was an

English

classical scholar and poet, best known to the general public for his cycle

of poems

A Shropshire Lad. Lyrical and almost

epigrammatic

in form, the poems wistfully evoke the dooms and disappointments of youth in

the English countryside.[1]

Their beauty, simplicity and distinctive imagery appealed strongly to late

Victorian and

Edwardian taste, and to many early 20th-century English composers both

before and after the

First World War. Through their song-settings, the poems became closely

associated with that era, and with

Shropshire itself. Look Not in my Eyes (1896), If Truth in Hearts that Perish (1896) and Shot? so Quick, so Clean an Ending (1896) are cited as examples in Sexual Heretics: Male Homosexuality in

English Literature from 1850-1900, by Brian Reade.

Alfred

Edward Housman (26 March 1859 – 30 April 1936), usually known as A. E. Housman, was an

English

classical scholar and poet, best known to the general public for his cycle

of poems

A Shropshire Lad. Lyrical and almost

epigrammatic

in form, the poems wistfully evoke the dooms and disappointments of youth in

the English countryside.[1]

Their beauty, simplicity and distinctive imagery appealed strongly to late

Victorian and

Edwardian taste, and to many early 20th-century English composers both

before and after the

First World War. Through their song-settings, the poems became closely

associated with that era, and with

Shropshire itself. Look Not in my Eyes (1896), If Truth in Hearts that Perish (1896) and Shot? so Quick, so Clean an Ending (1896) are cited as examples in Sexual Heretics: Male Homosexuality in

English Literature from 1850-1900, by Brian Reade.

Robert ‘Robbie’ Ross, another of Wilde’s loyal and devoted friends, also visited Wilde in prison, reciting to Oscar the poems from A. E. Housman’s poetry collection A Shropshire Lad, which were partly inspired by the trial and imprisonment of Wilde as well as other influences that had affected the homosexual poet. When Oscar was released from prison, Housman sent him a copy of the book.

Housman was one of the foremost classicists of his age and has been ranked as one of the greatest scholars who ever lived.[2][3] He established his reputation publishing as a private scholar and, on the strength and quality of his work, was appointed Professor of Latin at University College London and then at the University of Cambridge. His editions of Juvenal, Manilius and Lucan are still considered authoritative.

The eldest of seven children, Housman was born at Valley House in Fockbury, a hamlet on the outskirts of Bromsgrove in Worcestershire, to Sarah Jane (née Williams, married 17 June 1858 in Woodchester, Gloucester)[4] and Edward Housman (whose family came from Lancaster), and was baptised on 24 April 1859 at Christ Church, in Catshill.[5][6][7] His mother died on his twelfth birthday, and his father, a country solicitor, remarried, to an elder cousin, Lucy, in 1873. Housman's brother Laurence Housman and their sister Clemence Housman also became writers.

Valley House, the poet's birthplace

The site of the 17th-century Fockbury House (later known as The Clock

House). Home of A.E. Housman from 1873-1878

Home of A.E. Housman from 1860-1873 and again from 1878-1882. His younger

brother Laurence was born here in 1865.

Bromsgrove School

Westminster Abbey, London

Trinity College, Cambridge

Housman was educated at King Edward's School in Birmingham and later Bromsgrove School, where he revealed his academic promise and won prizes for his poems.[7][8] In 1877 he won an open scholarship to St John's College, Oxford and went there to study classics.[7] Although introverted by nature, Housman formed strong friendships with two roommates, Moses John Jackson and Alfred W. Pollard. Though Housman obtained a first in classical Moderations in 1879, his dedication to textual analysis, particularly of Propertius, led him to neglect the ancient history and philosophy that formed part of the Greats curriculum. Accordingly, he failed his Finals and had to return humiliated in Michaelmas term to resit the exam and at least gain a lower-level pass degree.[9][7] Though some attribute Housman's unexpected performance in his exams directly to his unrequited feelings for Jackson,[10] most biographers adduce more obvious causes. Housman was indifferent to philosophy and overconfident in his exceptional gifts, and he spent too much time with his friends. He may also have been distracted by news of his father's desperate illness.[11][12][13]

After Oxford, Jackson went to work as a clerk in the Patent Office in London and arranged a job there for Housman too.[7] The two shared a flat with Jackson's brother Adalbert Jackson until 1885, when Housman moved to lodgings of his own, probably after Jackson responded to a declaration of love by telling Housman that he could not reciprocate his feelings.[14] Two years later, Jackson moved to India, placing more distance between himself and Housman. When he returned briefly to England in 1889, to marry, Housman was not invited to the wedding and knew nothing about it until the couple had left the country. Adalbert Jackson died in 1892 and Housman commemorated him in a poem published as "XLII – A.J.J." of More Poems (1936).

Meanwhile, Housman pursued his classical studies independently, and published scholarly articles on such authors as Horace, Propertius, Ovid, Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles.[7] He gradually acquired such a high reputation that in 1892 he was offered and accepted the professorship of Latin at University College London (UCL).[7] When, during his tenure, an immensely rare Coverdale Bible of 1535 was discovered in the UCL library and presented to the Library Committee, Housman (who had become an atheist while still an undergraduate)[15] remarked that it would be better to sell it to "buy some really useful books with the proceeds".[16]

Although Housman's early work and his responsibilities as a professor included both Latin and Greek, he began to specialise in Latin poetry. When asked later why he had stopped writing about Greek verse, he responded, "I found that I could not attain to excellence in both."[17] In 1911 he took the Kennedy Professorship of Latin at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he remained for the rest of his life. G. P. Goold, Classics Professor at University College, wrote of Housman's accomplishments: "The legacy of Housman's scholarship is a thing of permanent value; and that value consists less in obvious results, the establishment of general propositions about Latin and the removal of scribal mistakes, than in the shining example he provides of a wonderful mind at work … He was and may remain the last great textual critic." [3] Between 1903 and 1930 Housman published his critical edition of Manilius's Astronomicon in five volumes. He also edited works by Juvenal (1905) and Lucan (1926).

Many colleagues were unnerved by his scathing attacks on those he thought guilty of shoddy scholarship.[7] In his paper "The Application of Thought to Textual Criticism" (1921) Housman wrote: "A textual critic engaged upon his business is not at all like Newton investigating the motion of the planets: he is much more like a dog hunting for fleas." He declared many of his contemporary scholars to be stupid, lazy, vain, or all three, saying: "Knowledge is good, method is good, but one thing beyond all others is necessary; and that is to have a head, not a pumpkin, on your shoulders, and brains, not pudding, in your head." [3][18]

His younger colleague A. S. F. Gow quoted examples of these attacks, noting that they "were often savage in the extreme".[19] Gow also related how Housman intimidated his students, sometimes reducing the women to tears. According to Gow, Housman (when teaching at University College London where, unlike Cambridge, he had students of both sexes) could never remember the names of his female students, maintaining that "had he burdened his memory by the distinction between Miss Jones and Miss Robinson, he might have forgotten that between the second and fourth declension". One of Housman's notable pupils at Cambridge was Enoch Powell.[20]

In his private life Housman enjoyed gastronomy, flying in aeroplanes and making frequent visits to France, where he read "books which were banned in Britain as pornographic".[21] But he struck A. C. Benson, a fellow don, as being "descended from a long line of maiden aunts".[22] His feelings about his poetry were ambivalent and he certainly treated it as secondary to his scholarship. He did not speak in public about his poems until 1933, when he gave a lecture "The Name and Nature of Poetry", arguing there that poetry should appeal to emotions rather than to the intellect.

Housman died, aged 77, in Cambridge. His ashes are buried just outside St Laurence's Church, Ludlow, Shropshire.[7][23]

My published books: