Queer Places:

Dzoragyugh 1st St, Yerevan 0015, Armenia

Komitas Pantheon

Yerevan, K'aghak' Yerevan, Armenia

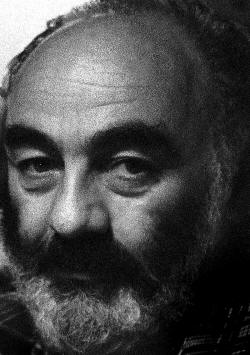

Sergei Parajanov (January 9, 1924 – July 20, 1990) was a Soviet Armenian film director, screenwriter and artist who made seminal contribution to world cinema with his films Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors and The Color of Pomegranates. Parajanov is regarded by film critics, film historians, and filmmakers to be one of the greatest and most influential filmmakers in cinema history.[1]

Sergei Parajanov (January 9, 1924 – July 20, 1990) was a Soviet Armenian film director, screenwriter and artist who made seminal contribution to world cinema with his films Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors and The Color of Pomegranates. Parajanov is regarded by film critics, film historians, and filmmakers to be one of the greatest and most influential filmmakers in cinema history.[1]

"Surrealism," "incitement to suicide," "traffic in art objects," and "leaning toward homosexuality" all sound like respectable weapons in the modern art arsenal. In the case of director Sergei Paradjanov, however, they were grounds for fifteen years of forced inactivity and, by the director's own reckoning, eight years of imprisonment in some of Russia's many pre-glasnost hard-labor camps. What was it about this jovial, bear-like man that invoked the unending wrath of censors? It could have been his abandonment of wife and children to live the unapologetic gay life he had apparently always desired. Even more damning, perhaps, were his films, a dozen features unabashedly celebrating Armenian (that is, non-Russian) folk culture, a Dionysian (some would say delirious) approach to his material, an indifference to social realism, and an air of rapturous and whimsical indulgence in color and sound--hardly the stuff to further the revolution. Paradjanov was born an ethnic Armenian on March 18, 1924 in Tiflis, the capital of the Georgian Republic. His first ambition was to be a singer, and to that end he attended the Tiflis Conservatoire from 1942 to 1945. However, an interest in cinema preempted these studies. He entered Moscow's State Institute in Cinematography, counting Lev Kuleshov and Alexander Dovzhenko among his teachers, and graduated in 1951. During the next ten years Paradjanov made a series of Ukrainian-language films based in the social realist tradition but containing subtle signs of a powerful visual imagination trying to break through. By 1964 Paradjanov brazenly abandoned state-dictated style entirely in favor of a purely celebratory folkloric approach. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, shot in the Carpathian mountains, features wild camera movements (including hand-held) and overripe color. This widely acclaimed film both put him on the international cinema map and brought him to the attention of Russian authorities, who could approve or reject his projects. Paradjanov's increasingly high profile as "anti-Russian," homosexual, and activist culminated in his first arrest in 1968. In 1974 he was sentenced under Russia's anti-gay law, Article 121, to five years at hard labor. In prison, Paradjanov created hundreds of artworks, some of them collages made from bits of wire, nails, flowers, and dried grass. "I can create beauty out of rubbish," he said. (Some of the works would have reinforced authorities' fears about him: Paradjanov made friends with other inmates and apparently sketched both their faces and their genitals.) Released a year early due to international protests, Paradjanov saw most of his proposed projects rejected, but managed to make three features before his death in 1990. Sympathetic response to this visionary's work requires an open mind and a willingness to be transported by his captivating imagery and lush scores, which evoke both the richness of Georgian-Armenian folk music and the high-art sounds of the great Russian composers. None of his films feature overtly gay themes, but they are infused with Paradjanov's queer sensibility, which manifests itself in lyrical tableaux of a vibrant minority culture whose mere existence stands in opposition to a repressive status quo.

The Color of Pomegranates (1972) is considered Paradjanov's masterpiece, but it is also one of his most challenging works. Nominally a biography of Armenian poet and troubadour Sayat Nova, the film opens with a series of striking tableaux vivants, most notably one in which the youthful Nova lies down in what looks like a concrete gully with seemingly endless books arranged around him, their pages fluttering fantastically in the breeze. Books are crucial in Paradjanov, not only because they contain and hold much of the world's artistic history, but also because much of his imagery is inspired by the ancient illuminated manuscripts to which he always managed to obtain access. (The Armenian church apparently liked him more than the Russian government did.) Nova's history is rendered as a kind of interiorized Bildungsroman, or coming of age story, tracing the boy's progress from early bookworm to apprentice rugmaker to devotee of the female body. "I am the man whose life and soul are tortured," reads a subtitle repeated throughout the film, but Paradjanov's colorful vision of a rich culture in which every dress is a tapestry and every man a handsome devil is far more upbeat than the phrase suggests. Paradjanov's much-remarked hubris is evident from the start of Pomegranates when he aligns himself with the Christian God by invoking the creation of the world. The Legend of Suram Fortress (1984) is less grandiose though no less mesmerizing. This charming picaresque tells of a plebe who gets his freedom and sets off to buy that of his wife, a fortune-teller. The film pivots on the concept that the Georgian way of life, symbolized by the besieged fortress of the title, can be saved only if a young man is willing to be walled up inside it. This metaphor for a rich regional culture threatened by an oppressive larger one was surely not lost on Paradjanov's detractors, but the film, with its gorgeous Georgian landscapes and fantastic imagery, happily, has outlived its enemies.

Paradjanov's final film, Ashik Kerib (1988), was dedicated to his late friend and compadre Andrei Tarkovsky, who also suffered tremendously at the hands of reactionary Russian authorities. Based on a story by Mikhail Lermontov and shot in the Georgia/Azerbaijan area that was Paradjanov's inspiration, the film is a typical phantasmagoria of folkloric imagery whose power is heightened by a rich score of regional music. Ashik is an impoverished minstrel (played by Yuri Mgoyan, a handsome petty criminal hired by Paradjanov). He must find "bride-money" to marry the daughter of a rich Turkish merchant. This simple plot gives Paradjanov plenty of room to play as Ashik encounters a series of tests in the classic heroic mold, and play he does in such unforgettable scenes as a "wedding of the blind, deaf and dumb" at which Ashik's music entrances the participants. Ashik's search is an immersion into the transcendent beauty and power of folk culture, which Paradjanov fleshes out with vivid colors, elaborate costumes and headgear, and riotous blends of music, dance, and movement. Even the simplest images show the director's constant theme of the triumph of nature over the temporal, as when falling rose petals replace the dowry of diamonds that Ashik cannot afford. Some critics have seen Ashik Kerib as a parable for Paradjanov's oppression by the government, with the director himself represented by the hapless lute player wandering through a blasted landscape of lost souls. But this interpretation misses the celebratory, indeed transcendent quality of image and sound that are the film's driving force. If Paradjanov was not reconciled to the political abuse he suffered, it is impossible to tell from his final film.

After Paradjanov's death on July 21, 1990, his home in Yerevan was converted into a museum containing some of his writings (Leonid Alekseychuk says he wrote 23 scripts and 50 volumes of diaries) and several hundred of his artworks, including some he made during his imprisonment.

My published books: