Queer Places:

18 Hechangtang, Yuecheng Qu, Shaoxing Shi, Zhejiang Sheng, China, 312011

Gushan Park, Xiling Bridge Bank, Xihu District, Hangzhou 310007

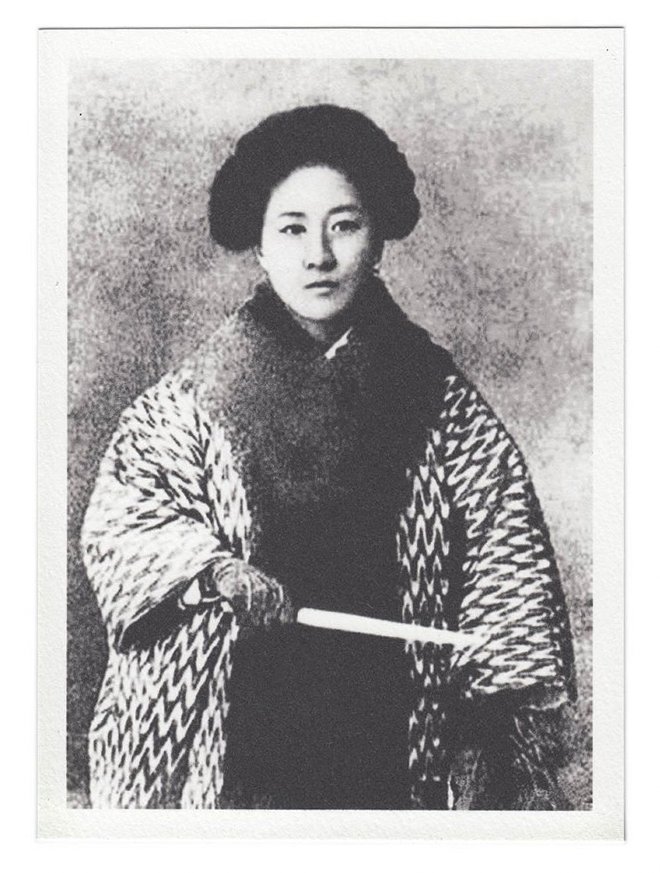

Qiu

Jin (November 8, 1875 – July 15, 1907) was a Chinese revolutionary, feminist,

and writer. Her courtesy names are Xuanqing and Jingxiong. Her sobriquet name

is Jianhu Nüxia which, when translated literally into English, means "Woman

Knight of Mirror Lake". Qiu was executed after a failed uprising against the

Qing dynasty, and she is considered a national heroine in China; a martyr of

republicanism and feminism.

Qiu

Jin (November 8, 1875 – July 15, 1907) was a Chinese revolutionary, feminist,

and writer. Her courtesy names are Xuanqing and Jingxiong. Her sobriquet name

is Jianhu Nüxia which, when translated literally into English, means "Woman

Knight of Mirror Lake". Qiu was executed after a failed uprising against the

Qing dynasty, and she is considered a national heroine in China; a martyr of

republicanism and feminism.

Born in Xiamen, Fujian,[1] Qiu grew up in her ancestral home, Shanyin Village, Shaoxing, Zhejiang. While in an unhappy marriage, Qiu came into contact with new ideas. She became a member of the Triads and Tongmenghui secret society[2] who at the time advocated the overthrow of the Qing and restoration of Han Chinese governance.

In 1903, she decided to travel overseas and study in Japan[3], leaving her two children behind. She initially entered a Japanese language school in Surugadai, but later transferred to the Girls' Practical School in Kōjimachi, run by Shimoda Utako.[4] Qiu was fond of martial arts, and she was known by her acquaintances for wearing Western male dress[5][6][7] and for her nationalist, anti-Manchu ideology. She joined the anti-Qing society Guangfuhui, led by Cai Yuanpei, which in 1905 joined together with a variety of overseas Chinese revolutionary groups to form the Tongmenghui, led by Sun Yat-sen.

Within this Revolutionary Alliance, Qiu was responsible for the Zhejiang Province. Because the Chinese overseas students were divided between those who wanted an immediate return to China to join the ongoing revolution and those who wanted to stay in Japan to prepare for the future, a meeting of Zhejiang students was held to debate the issue. At the meeting, Qiu allied unquestioningly with the former group and thrust a dagger into the podium, declaring: "If I return to the motherland, surrender to the Manchu barbarians, and deceive the Han people, stab me with this dagger!" She subsequently returned to China in 1906 along with some 2,000 other students.[8]

Whilst still based in Tokyo, Qiu single-handedly edited a journal entitled Vernacular Journal (Baihua Bao). The journal published a number of issues using vernacular Chinese as a medium of revolutionary propaganda. In one issue, Qiu wrote a manifesto entitled "A Respectful Proclamation to China's 200 Million Women Comrades", where she lamented the problems caused by bound feet and oppressive marriages[9]. Having suffered from both ordeals herself, Qiu explained her experience in the manifesto and received an overwhelmingly sympathetic response from her readers.[10] Also outlined in the manifesto was Qiu's belief that a better future for women lay under a Western-type government instead of the Qing government that was in power at the time. She joined forces with her cousin Xu Xilin[5] and together they worked to unite many secret revolutionary societies to work together for the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty.

She was an eloquent orator[11] who spoke out for women's rights, such as the freedom to marry, freedom of education, and abolishment of the practice of foot binding. In 1906 she founded a radical women's journal with another female poet, Xu Zihua[12], called China Women's News (Zhongguo nü bao), though it published only two issues before it was closed by the authorities.[13] In 1907 she became head of the Datong school in Shaoxing, ostensibly a school for sport teachers, but really intended for the military training of revolutionaries.

On July 6, 1907 Xu Xilin was caught by the authorities before a scheduled uprising in Anqing. He confessed his involvement under torture and was executed. On July 12, the authorities arrested Qiu at the school for girls where she was the principal. She was tortured as well but refused to admit her involvement in the plot. Instead the authorities used her own writings as incrimination against her and, a few days later, she was publicly beheaded in her home village, Shanyin, at the age of 31[14]. Her last written words, her death poem, uses the literal meaning of her name, Autumn Gem, to lament of the failed revolution that she would never see take place.

Qiu was immortalised in the Republic of China's popular consciousness and literature after her death. She is now buried beside West Lake in Hangzhou. The People's Republic of China established a museum for her in Shaoxing, named after Qiu Jin's Former Residence.

Her life has been portrayed in plays, popular movies and a documentary (Autumn Gem)[16]. One film, simply entitled Qiu Jin, was released in 1983 and directed by Xie Jin;[17][18]. Another film, released in 2011, was entitled Jing Xiong Nüxia Qiu Jin, or The Woman Knight of Mirror Lake, and directed by Herman Yau. She is briefly shown in the beginning of 1911, being led to the execution ground to be beheaded. The movie was directed by Jackie Chan and Zhang Li. Immediately after her death Chinese playwrights used the incident, "resulting in at least eight plays before the end of the Ch'ing dynasty."[19]

In 2018, the New York Times published a belated obituary for her.[20]

Because Qiu is mainly remembered in the West as revolutionary and feminist, her poetry and essays are often overlooked (though owing to her early death, they are not great in number). Her writing reflects an exceptional education in classical literature, and she writes traditional poetry (shi and ci). Qiu composes verse with a wide range of metaphors and allusions that mix classical mythology with revolutionary rhetoric.

My published books: