Queer Places:

Corcoran Gallery of Art, 500 17th St NW, Washington, DC 20006, Stati Uniti

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 118-128 N Broad St, Philadelphia, PA 19102, Stati Uniti

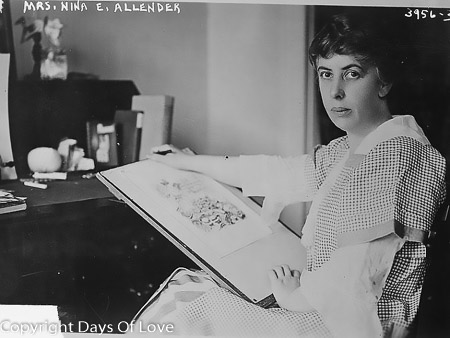

Nina

Evans Allender (December 25, 1873 – April 2, 1957) was an American artist,

cartoonist, and women's rights activist.[1]

She studied art in the United States and Europe with William Merritt Chase and

Robert Henri. Allender worked as an organizer, speaker, and campaigner for

women's suffrage and was the "official cartoonist" for the National Woman's

Party's publications, creating what became known as the "Allender Girl."

Nina

Evans Allender (December 25, 1873 – April 2, 1957) was an American artist,

cartoonist, and women's rights activist.[1]

She studied art in the United States and Europe with William Merritt Chase and

Robert Henri. Allender worked as an organizer, speaker, and campaigner for

women's suffrage and was the "official cartoonist" for the National Woman's

Party's publications, creating what became known as the "Allender Girl."

Nina Evans Allender was born on Christmas Day, December 25, 1873 in Auburn, Kansas.[2][3][a] Her father, David Evans was from Oneida County, New York and moved to Kansas, where he served as a teacher before becoming superintendent of schools.[6] Her mother, Eva Moore,[6] was a teacher at a prairie school.[7][8] The Evanses lived in Washington, D.C. by September 1881 when Eva Evans was working at the Department of the Interior as a clerk in the Land Office. She worked there until August 1902,[6][9][7] and she was one of the first women to be employed by the federal government.[3] David Evans worked at the United States Department of the Navy as a clerk[10] and was a poet[11][12][13] and short story writer.[14] He died on December 13, 1906 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.[10]

In 1893, at the age of 19 Nina Evans married Charles H. Allender.[15][16] Some years later Charles Allender reportedly took a sum of money from the bank where he worked and ran off with another woman.[7] Abandoned by her husband,[15] Nina sued Charles for divorce in January 1905, alleging infidelity.[17] Their divorce was granted that year.[18][19]

About 1906 her portrait was painted with fellow artist Charles Sheeler by Morton Livingston Schamberg. It was formerly in the collection of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., but when that museum closed it was transferred to the National Gallery of Art.[20] Following her years abroad studying art, Allender worked at the Treasury Department[21] and the Government Land Office in Washington, D.C.[15] She lived in Washington, D.C. in 1916[2] and maintained an art studio in New York City by 1917.[22]

In 1913, Nina were recruited into the Congressional Union of NAWSA[21], later the National Woman's Party by Alice Paul[15][34] when she was in Washington D.C. to lead the Congressional Committee of NAWSA.[35] Inez Haynes Irwin stated that Nina had readily agreed to make monthly financial donations and volunteer their time for the organization.[36]

Integral to the women's rights and suffrage campaigns were its newspapers.[b] The Congressional Union under Alice Paul founded its own periodical, The Suffragist, in 1913.[48] Allender was the key artist for the publication[21] which featured political cartoons. The writers were Alice Paul and Rheta Childe Dorr, the founding editor,[49] who came to Washington at the urging of Paul and Lucy Burns, another suffrage leader.[50] Allender, having been coaxed by Paul, found she had a talent for drawing cartoons and became The Suffragist's "official cartoonist".[49][51] Her first political cartoon, which portrayed the campaign and women's need for the ballot, was published in the June 6, 1914 issue on heavy 10" x 13" paper.[52] The entire front page was subsequently occupied by a cartoon by Nina Allender. A 1918 review of her work conceded that her early period "dealt with old suffrage texts, still trying to prove that woman's place was no longer in the home."[52]

Early 20th-century American cartoons had enjoyed the Gibson Girl from Charles Dana Gibson and the Brinkley Girl from Nell Brinkley.[51] Allender was credited with producing 287 political cartoons regarding suffrage.[53] Her depiction of the "Allender girl," captured the image of a young, capable American woman,[54] embodying "the new spirit that came into the suffrage movement when Alice Paul and Lucy Burns came to the National Capital in 1913."[51]

In 1942, Allender moved to Chicago, Illinois where she remained for over a decade. In 1955 she moved to Plainfield, New Jersey, where a niece, Mrs. Frank Detweiler (Joan) resided.[1] She died at her niece's Plainfield house on April 2, 1957.[23][3][1]

My published books:

Mrs. Nina E. Allender, 85, of 1200 W. Seventh St., one of the fighters for women's suffrage and equal rights, died yesterday at home. ...