Queer Places:

Smith College (Seven Sisters), 9 Elm St, Northampton, MA 01063

Bryn Mawr College (Seven Sisters), 101 N Merion Ave, Bryn Mawr, PA 19010

New York University, 22 Washington Square North, New York, NY 10011

Gomez Mill House, 11 Mill House Rd, Marlboro, NY 12542

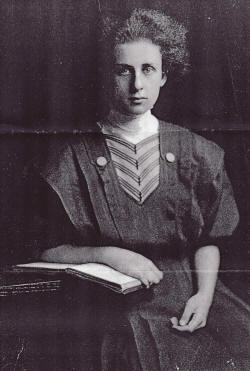

Martha

Gruening (1889 – October 28, 1937) was an American journalist, lawyer, and Civil Rights

activist. In her work, she easily recognized the intersection of gender, race,

and class. The government perceived her as a danger to the status quo, and

though it tried to silence her, she did not back down from the controversy

that her efforts brought to her life. Gruening was a progressive lawyer, educator, and journalist; assistant secretary of NAACP, she was arrested for supporting strikers and distributing anti-conscription literature. She ran a libertarian school in Marlborough, New York, and wrote for the Modern School magazine; she also attended Henri’s and Bellow’s art class at the Ferrer Center. With W.E.B. DuBois, she investigated race riots in Illinois and Texas, and published her accounts in Pearson’s Magazine (Sept 1917) and The Crisis (Nov 1917); she served on the New York Publicity committee of the AB San Francisco Labor Defense; she testified on behalf of

Emma Goldman at her anti-draft

trial.

Martha

Gruening (1889 – October 28, 1937) was an American journalist, lawyer, and Civil Rights

activist. In her work, she easily recognized the intersection of gender, race,

and class. The government perceived her as a danger to the status quo, and

though it tried to silence her, she did not back down from the controversy

that her efforts brought to her life. Gruening was a progressive lawyer, educator, and journalist; assistant secretary of NAACP, she was arrested for supporting strikers and distributing anti-conscription literature. She ran a libertarian school in Marlborough, New York, and wrote for the Modern School magazine; she also attended Henri’s and Bellow’s art class at the Ferrer Center. With W.E.B. DuBois, she investigated race riots in Illinois and Texas, and published her accounts in Pearson’s Magazine (Sept 1917) and The Crisis (Nov 1917); she served on the New York Publicity committee of the AB San Francisco Labor Defense; she testified on behalf of

Emma Goldman at her anti-draft

trial.

Martha was the youngest daughter of Dr. Emil Gruening, a renowned ophthalmologist who came from Prussia and studied medicine in the States. She spoke German at home, then learned French and took in European art and culture in grade school abroad.

She attended the Ethical Culture School, which The New York Society for Ethical Culture (NYSEC) founded under the direction of Dr. Felix Adler. There, she learned views on social justice, racial equality, and intellectual freedom that her parents championed; dinner table conversations engaged her in politics and international news. The school didn’t have quotas and sourced many of its students through scholarship, so Martha studied in an environment that erased class division. And her parents encouraged the public service that the school expected of its students. The foundation for her life’s work was well built.

She attended Smith College, founding a women’s suffrage club there, and earned her undergraduate degree in 1909. Pursuing advanced studies at Bryn Mawr, her suffrage work got her selected as the Secretary of the National College Equal Suffrage League.

She chose Bryn Mawr to prepare for Johns Hopkins, but the Philadelphia Shirtwaist Strike changed that plan. She was arrested in January 1910 while observing a protest by factory workers. (The women were mostly Russian Jews newly arrived to the United States and Martha saw they were not being given the opportunity they sought.) The arresting officer described her as 'a brick in a soft hat:' a hidden danger in plain sight. The judge told Martha she had no business watching the police, that trouble makers like her were the only reason the strike remained unsettled. She was indicted by a grand jury on a false charge of attempting to incite a riot. Rather than seek her bail, which the poor girls could not afford, Martha chose solidarity and stayed the night in Philadelphia’s notorious Moyamensing Prison. Not missing a beat in her righteous indignation, Martha contacted the press. She recounted these events in the February 16, 1910 edition of The New York Call- a socialist daily newspaper published 1908-1923. Her tenacity paid off, the false charges were dismissed.

Martha passing out suffrage literature, 1912. Paul Thompson/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

This invaluable lesson on police misconduct, the corrupt legal system, class-based inequities, and the power of the press, convinced her to begin work as a free-lance journalist and become an attorney. Graduating Bryn Mawr, she travelled across the country as an organizer for women’s suffrage, then enrolled in NYU School of Law in 1912. She graduated in 1914 with a Juris Doctorate.

While Martha’s early advocacy focused on women’s suffrage, she quickly learned it was part of a broader movement to gain civil rights guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution for all Americans. Yet, the North American Women's Suffrage Association rejected her suggestions to include black women and to show solidarity with civil rights activists. Martha emphasized the connection between women’s suffrage and Black civil rights in "Two Suffrage Movements" published in September 1912 in NAACP magazine The Crisis- a leading platform in the pursuit of racial equality. She warned suffragists of the peril in not supporting their fellows working toward similar goals for African Americans. She knew the difference between true equality and preferential status.

Martha then dove into civil rights work. She served as NAACP National Board Asst. Secretary 1912-1914, while studying law. She also held the position 1917-1918. She wrote a seminal article, “With Malice Aforethought,” printed January 1916 in The Forum. She covered the East St. Louis and Houston riots in 1917 with W.E.B. Du Bois, writing in-depth copy with him. As a white journalist, she gained access to places Du Bois couldn't; as a feminist, her profiles of black women were unique. She was named Special Investigator for the NAACP Lynching Fund in 1918, working with NAACP Field Investigator Helen Boardman to compile and analyze verifiable data. They organized the NAACP’s first book, 30 Years of Lynching in the United States 1889-1918. She then became Secretary to NAACP Director of Public Relations, Herbert J. Seligmann, from 1918 to 1920.

Martha also engaged in anti-war activism before, during, and after U.S. involvement in WWI. In 1916, she was arrested for distributing pacifist and no-conscription literature that she wrote. In 1917 she co-founded the New York Bureau of Legal First Aid, renamed NY Bureau of Legal Advice- the first U.S. civil liberties organization to offer free legal services especially to conscientious observers. Martha felt the draft was a violation of Constitutional protections. Accused of anti-conscription activities in June 1917, the Bureau was investigated, then raided by Federal officers in September 1918. It was illegal to boycott the draft and to encourage resistance to it. In April 1919, Gruening co-signed the “Statement of the NY Bureau of Legal Advice” denouncing the U.S. War Department for imprisoning conscientious objectors in solitary confinement.

Martha’s friendship and professional relationship with W.E.B. Du Bois started in 1911 with her interest in addressing differences between the education of white and black children. In 1914, she began attending Robert Henri's art classes at the New York Ferrer Center at The Modern School; there she was introduced to the merits of libertarian education.

An unmarried white Jewish woman, in 1915 Martha adopted African-American David Butt (1912-1936). His parents were Negro Theatre performers from South Carolina who could not afford to care for a third child. Martha raised David through prejudice and her financial struggles as an independent female journalist.

Determined to give David a proper education in the States, and now armed with an inheritance from her late father, Martha bought the Gomez Mill House in June 1918, to establish a school on the site. In 1919, 'Mill House' school was advertised in Asa Philip Randolph's Civil Rights magazine, The Messenger, as a ‘Libertarian International School’ and ‘Country School For Colored Children and Others’ to teach a broad curriculum that upheld the rights of all children.

Though Martha was drawn to European education models, having started 'Mill House' school it's unclear why she moved to Paris after the war. Perhaps it was not ready for David. She enrolled him at Odenwaldschule in Germany, found work at the Paris Herald, and went to progressive education conventions where she mentioned her school.

She chose her friend and NAACP collaborator, Helen Boardman, to partner on Mill House school since Helen worked at the New York Bureau of Education Experiments (later Bankstreet College.) Even though the school was listed as established in a 1921 almanac, there is no evidence it opened. Martha remained in Paris, with David in the German boarding school, for several years after she gave Helen power of attorney to sell the Mill House in 1923.

Martha returned to the U.S. in 1929 and picked up where she left off in her civil rights work. During the 1930s she wrote important articles on the subject, even questioning the tenacity of the NAACP regarding a court case that involved a victim of racism.

In 1934, Martha's adopted son David lived in Harlem, reunited with his siblings. He was attending City College, but dropped out due to severe illness. Sadly, David lost his battle with tuberculosis on June 27, 1936. His death at just 25 years old devastated Martha. She moved to Northampton, MA presumably to work at Smith College, but she was not long for this world either. On October 28, 1937, at age 48, Martha suffered a brain aneurysm which took her life.

Martha kept up her efforts to fight injustice right to the end. The Nation printed a piece she wrote a month before her death, and the New York Times printed one a few days after she passed. She lived her whole life becoming and being an unflinching activist and journalist, working tirelessly for civil rights and progressive ideals. She lived her values with passionate confidence, confronting widely-held unfair views when it meant facing the consequences. And although Martha Gruening is so unique, she is but one of many heroes in the fight for equality and justice for all.

My published books: