Husband Dang Thuong Nguyen

Queer Places:

Charterhouse School, Hurtmore Rd, Godalming GU7 2DX

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

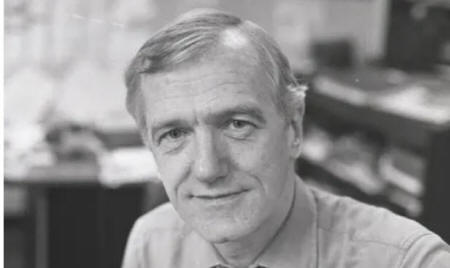

Frederick Mark Frankland (April

19, 1934 - April 12, 2012) was a handsome and clever young MI6 desk officer

with an aristocratic pedigree who resigned from the service to become an

award-winning foreign correspondent and the author of several good books. The

most successful of these was Child of My Time: An Englishman's Journey in a

Divided World (1999), a frank and literary memoir that won Frankland the PEN/Ackerley prize for autobiography.

Frederick Mark Frankland (April

19, 1934 - April 12, 2012) was a handsome and clever young MI6 desk officer

with an aristocratic pedigree who resigned from the service to become an

award-winning foreign correspondent and the author of several good books. The

most successful of these was Child of My Time: An Englishman's Journey in a

Divided World (1999), a frank and literary memoir that won Frankland the PEN/Ackerley prize for autobiography.

As a correspondent in Moscow, Saigon and Washington, Frankland was able to view this divided world from both sides. During his 30 years with the Observer (1962-92), he reported on the two great pivotal events of the last quarter of the 20th century. In the spring of 1975, he witnessed the fall of Saigon and was on one of the last US Marine Corps helicopters to leave the South Vietnamese capital. Then, in 1989, he covered the uprisings in eastern Europe that marked the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the cold war.

His reportage of the disintegrating Warsaw Pact became the basis of The Patriots' Revolution – How Eastern Europe Toppled Communism and Won Its Freedom (1990). The book received accolades on both sides of the Atlantic. But when, nine years later, he published his tightly written and often elegiac memoir, the atmospheric detail supplied in his vignettes of life in Moscow and Saigon, particularly the louche underworld of Soviet Russia, was recognised as an absorbing and often iconoclastic read that went far beyond most contributions to the historiography of the cold war. "Frankland has a particular sympathy with outsiders and the betrayed. As a gay man in intolerant times and places, he knew he would never be on the side of the powerful, would always feel for underdogs," wrote the transgender author Roz Kaveney.

Frankland was a direct descendant of the British diplomat, travel writer and expert on the Orthodox monasteries of the Levant, Robert Curzon, 14th Baron Zouche, whose granddaughter married the Yorkshire baronet Sir Frederick Frankland. Family tradition saw to it that, a century later, young Frankland followed Curzon of the Levant to Charterhouse from where, in 1952, he obtained a major scholarship to study history at Pembroke College, Cambridge. But he did not go there immediately. University entrants could apply to have their two years' national service in one of the armed services deferred, but the more adventurous seized the chance of a break between classroom and campus.

Frankland volunteered for the Royal Navy, where there was an appetite to train people with proven academic ability as Russian translators. He liked learning Russian, rapidly acquiring a working knowledge. And, as he revealed in his memoir, the navy provided the 18-year-old Frankland with a newfound opportunity for gay sex. This section rather startled some old friends. It was not that anybody doubted his sexuality, but he had always been discreet about it; neither proud nor ashamed to be gay.

After Cambridge and a postgraduate year in the US, he joined the Secret Intelligence Service, another family tradition. During the second world war, his father, Wing Commander Roger Frankland, a radio expert, had been attached to SIS's crucial codebreaking unit at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire.

Basic training included a pistol-shooting course with Browning automatics: no fancy two-handed grips, but swivel on your left heel, point your weapon and give the target two bullets. Frankland soon concluded that the real point of all this was to engender a sense of mission and apartness. Reality was the commute to St James's Park underground and his desk at Broadway Buildings, MI6's headquarters until 1964, and it rapidly began to pall. He found the work tedious: he was given little opportunity to use his Russian, and the company was uninspiring. He began to pity the agents whose lives were in their hands.

After a year, he quit. He had decided to become a journalist and found employment on Time & Tide, an ailing but respectable political weekly whose contributors had included George Orwell. By 1962, he was on David Astor's Observer and bound for Moscow. Unfortunately, so was another of Astor's journalists. A KGB defector had at last provided all the necessary evidence to hang Kim Philby, who had fled Beirut, where, with MI6's blessing, he had become Middle East correspondent for the Observer and the Economist.

Frankland had met Philby in the Broadway Buildings and he always suspected that Philby had identified him to the Russians, who would have probably shown him photographs of all the British residents in Moscow who might conceivably be working for MI6. There was a certain amount of harassment, but they did not throw him out. That happened in 1985 when, during his second and last stint in Moscow, he was expelled in retaliation for Britain's expulsion of several alleged KGB residents in London.

In 1967, Frankland was transferred to Saigon. To his amazement, the SIS man at the British embassy there soon indicated that his old masters suspected that his five years in Moscow had resulted in him being turned by the KGB. Otherwise, they would have kicked him out, wouldn't they? Nor did it help when, shortly after his arrival, Frankland scooped the resident press corps by interviewing a Viet Cong unit in a hamlet a risky hour's drive away from the city. How could he have done it without special contacts provided by Hanoi's Russian patrons? Answer: because the new correspondent had discovered that Mister Loc, the Observer's office manager, was VC himself and understood the value of publicity.

MI6 was hopelessly wrong. Frankland had no sympathy for Moscow's clients in Hanoi, and respected the fear and loathing so many South Vietnamese held for them. There were moments when he was disgusted by American behaviour. But by the time the war ended, he believed that by far the worst thing they had done was betray their Vietnamese allies by abandoning them to their fate.

Frankland went with them. The helicopter evacuation was a story in itself and another Observer reporter was staying behind to cover whatever followed. But there was another reason for his departure. He knew the men from the Soviet embassy in Hanoi would arrive shortly after the first North Vietnamese tanks and they would certainly have a file on him.

One of the last things he did before he left was give his Observer colleague most of his remaining US dollars. In later life, his conviction that the American withdrawal had been a great betrayal, the cause of thousands of unnecessary deaths as Vietnamese asylum seekers tried to flee Communist rule across the South China Sea, remained as firm as ever.

Unlike most foreign correspondents – and indeed spies – Mark Frankland was the opposite of gregarious. He loathed big parties, and the idea of joining a London gentleman's club, to which his pedigree and interests would have made him eminently suited, was anathema. The only "club" he ever felt comfortable in was the pub near the Observer's old HQ known affectionately as "Auntie's".

Frankland settled back in Britain by 1982 and he arranged, with some difficulty, for his long-term Vietnamese partner, Dang Thuong Nguyen, to come to England, and the two of them were essentially home-birds. In May 2006, Mark and Thuong entered into a civil partnership at a ceremony at Fulham registry office. The bubbly female registrar was surprised that there were only two other people invited, namely the two witnesses: the businessman Robin Hope, who had studied Russian with Mark in the navy, and Jonathan Fryer. This was typical of Mark's sense of privacy and modesty, and, after the ceremony, the four of them walked down the road to a Thai restaurant for lunch.

My published books:/p>