Partner Enid Marx

Queer Places:

Coffyns, Cross Meadow, Spreyton, Crediton EX17, UK

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

St Michael Churchyard

Spreyton, West Devon Borough, Devon, England

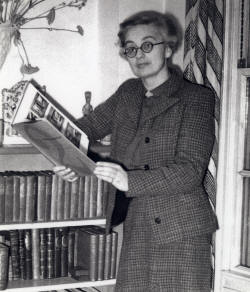

Margaret Barbara Lambert

(7 November 1906 - 22 January 1995) was an historian; she was Assistant

Editor, British Documents on Foreign Policy 1946-50; Lecturer in Modern

European History, University College of the South-West (Exeter) 1950-51;

British Editor-in-Chief, German Foreign Office Documents 1951-83; Lecturer in

Modern European History, St Andrews University 1956-60; CMG 1965.

She also collected and wrote about English folk art with her partner, the designer Enid Marx. During the late 1950s and 1960s, Lambert lived with Enid Marx in St Andrews, Scotland,

where Lambert lectured in history at St Andrews University.

Margaret Barbara Lambert

(7 November 1906 - 22 January 1995) was an historian; she was Assistant

Editor, British Documents on Foreign Policy 1946-50; Lecturer in Modern

European History, University College of the South-West (Exeter) 1950-51;

British Editor-in-Chief, German Foreign Office Documents 1951-83; Lecturer in

Modern European History, St Andrews University 1956-60; CMG 1965.

She also collected and wrote about English folk art with her partner, the designer Enid Marx. During the late 1950s and 1960s, Lambert lived with Enid Marx in St Andrews, Scotland,

where Lambert lectured in history at St Andrews University.

Margaret Lambert was quite literally born into politics. Her mother was Barbara Stavers. Her father, George Lambert, 1st Viscount Lambert, was Civil Lord of the Admiralty from 1905 to 1915 and, on his death in 1958, had the distinction of being the last man to have been an MP under Gladstone. Margaret used to recall that, when she was a child, the then Mr and Mrs Churchill came to stay at the Lambert family house, Coffyns, in north Devon; on returning from a day's rough shooting, Winston Churchill would at once demand, "Clemmie! Where's Clemmie?"

Not long after the end of the Great War, Margaret and her elder sister Grace accompanied their father on a tour of the war cemeteries in Belgium and northern France, which left her with an indelible memory of the cost and the pity of war.

In the early 1930s she had met her partner, the designer Enid Marx. Both were members of a team sent out to Germany at the end of 1946, part of a Council of Industrial Design (COID) initiative to survey education in industrial design with a view to improving that at home, reflecting Lambert’s connections as much as Marx’s design experience. Other surveys followed in Sweden, Denmark and Finland, Lambert contributing essays on the Finnish (with Marx) and German trips to George Weidenfeld’s (another former BBC colleague) Contact Books. In September 1947 the pair set out for Italy, this time as a pilot study, Lambert armed with letters of introduction from the COID’s Cycill Tormley, hotel recommendations from Veronica Wedgwood and contacts in Radio Italiano from her BBC days.

Very usefully for a budding historian, her background furnished her with a wealth of helpful introductions, amongst others to prominent personages in the Saar. After Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, she did a doctorate at the London School of Economics on theregion. While she was there, gathering material for the book (The Saar, 1934) which she published in the run-up to the 1935 plebiscite, she described her discoveries and experiences in letters to her father. He found one such letter so striking that he sent it on to Sir John Simon (at that time Foreign Secretary).

It described how, although the Saarlanders had not yet formally voted to be re-united with Germany, they were already in the grip of National Socialist fervour; a group of Jewish boys, who could not of course join the recently founded local branch of theHitler Youth, had prevailed upon their mothers to make them imitation uniforms, and, proudly wearing these, carried out imitation Hitler Youth exercises in the sitting-room of one of their parents' houses. (The letter re-surfaced quite by chance one dark December afternoon in the 1960s when Margaret Lambert was working as usual on the German documents in her room overlooking the Thames by Waterloo: it was brought in for her to see by one of the Foreign Office "weeders".)

After her wartime work with the BBC (which, as she let fall only very much later, involved amongst other things the extraction of information from German POW generals in the course of chats over the teacups - Lambert spoke excellent German - in various country houses where these officers were detained), she became, first, an assistant editor on the British diplomatic documents and, subsequently, British editor-in-chief of the captured German diplomatic documents, retaining her connection with this grandly conceived international project until 1983. Her editorial work was interspersed with periods of university teaching.

Both as editor and teacher, Margaret Lambert displayed qualities of a very high order. She possessed great patience, alike in teasing out the puzzles posed by vast quantities of documents, not originally stored up for the benefit of the historian and rendered harder to handle by the vicissitudes of war, and in encouraging her students to surpass what they thought were their own limits. Her remarkable memory permitted her to call on great reserves of knowledge at will in order to elucidate knotty points,whilst at the same time she brought to the work of editing a highly refined judgement.

The process of selecting material for publication from the many tons of papers which had been flown to Britain for greater safety at the time of the blockade of Berlin and the resultant airlift did not unfold entirely without difficulty. As may be imagined, there were occasions (albeit creditably few) when the thought was mooted that this or that document might be better not made public. However, with endless tact and negotiating skill, and calling once again when necessary on her old connections, Lambert succeeded in ensuring that no gaps were left in the published record.

With her lifelong friend the artist Enid Marx, she shared a wide-ranging and well-informed love of English popular art; it was one of the ladies' great pleasures to go foraging round the countryside for old inn-signs, inscriptions on tombstones, pieces of regional pottery, gingerbread moulds, in short, for examples of the products of scores of traditional crafts which their knowledgeable eye enabled them to spot. They maintained a network of contacts with continental and American collectors, so that their appreciation of an English piece was heightened by their being able to compare it with its European or American equivalent, and collaborated in two accounts of the subject, English Popular and Traditional Art (1946) and English Popular Art (1952).

Whether as a historian, in which capacity she firmly and unswervingly sought to lay bare truth, as a cherisher of the arts and crafts of the (usually nameless) "humbler people", as a teacher, or as a practitioner of the art of friendship, Margaret Lambert added not inconsiderably to the sum of civilisation.

She died London 22 January 1995.

My published books: