Partner Teresa de la Parra, María Teresa de Rojas

Queer Places:

525 Valencia Ave, Coral Gables, FL 33134, apartment 4

Caballero Rivero Woodlawn North, 3260 SW 8th St, Miami, FL 33135

Lydia

Cabrera (May 20, 1899, in

Havana, Cuba – September 19, 1991, in

Miami, Florida) was a Cuban

independent ethnographer.

Lydia

Cabrera (May 20, 1899, in

Havana, Cuba – September 19, 1991, in

Miami, Florida) was a Cuban

independent ethnographer.

Cabrera was a Cuban writer and literary activist. She was an authority on Santería and other Afro-Cuban religions. During her lifetime she published over one hundred books; little of her work is available in English. Her most important book is El Monte (Spanish: "The Wilderness"), which was the first major ethnographic study of Afro-Cuban traditions, herbalism and religion. First published in 1954, the book became a "textbook" for those who practice Lukumi (orisha religion originating from the Yoruba and neighboring ethnic groups) and Palo Monte (a central African faith) both religions reaching the Caribbean through African slaves. Her papers and research materials were donated to the Cuban Heritage Collection - the largest repository of materials on or about Cuba located outside of Cuba - forming part of the library of the University of Miami. A section in Guillermo Cabrera Infante's book Tres Tigres Tristes is written under Lydia Cabrera's name, in a comical rendition of her literary voice. She was one of the first writers to recognize and sensitively publish on the richness of Afro-Cuban culture and religion. She made valuable contributions in the areas of literature, anthropology, art, ethnomusicology, and ethnology.

In El Monte, Cabrera fully described the major Afro-Cuban religions: Regla de Ocha (commonly known as Santeria) and Ifá, which are both derived from traditional Yoruba religion; and Palo Monte, which originated in Central Africa. Both the literary and anthropological perspectives in Cabrera's work assume that she wrote about mainly oral, practical religions with only an “embryonic” written tradition. She is credited by literary critics for having transformed Afro-Cuban oral narratives into literature, which is, written works of art, while anthropologists rely on her accounts of oral information collected during interviews with santeros, babalawos, and paleros, and on her descriptions of religious ceremonies. There is a dialectical relationship between Afro-Cuban religious writing and Cabrera's work; she used a religious writing tradition that has now internalized her own ethnography.

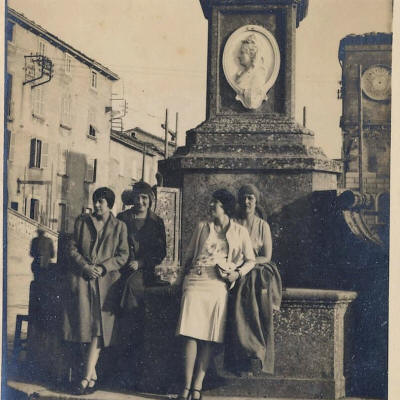

Lydia Cabrera and María Teresa de Rojas at Quinta San José, Havana

Born in Havana in 1899 as the youngest of eight siblings, Cabrera came from a family of high socio-economic status in Cuba. Her father, Raimundo Cabrera, was a writer, lawyer, prominent man in society, and an advocate for Cuba's independence. Her mother, Elisa Marcaida Casanova, was a housewife and respected socialite. Her father was also the president of the first Cuban corporation, La Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País, founded in the eighteenth century. He owned a popular literary journal, Cuba y America, where Lydia got her first experience as a writer. At the age of thirteen, Cabrera wrote a weekly anonymous column that appeared in her father's journal. She covered topics relevant to her specific community, such as wedding announcements, childbirths, or obituaries.[1]

The family had many Afro-Cuban servants and child caretakers, through whom young Lydia learned about African folklore, stories, tradition, and religions. Like the majority of wealthy Cubans in the early 1900s, the family had private tutors who came to the home of the Cabreras to educate the children. For a short period of time, she attended the private school of Maria Luisa Dolz. At that time it was not socially acceptable for a woman to pursue a high school diploma, so Cabrera finished her secondary education on her own.[2]

By 1927 Cabrera wanted to make money on her own and to become independent of her family. She moved to Paris to study art and religion at L'Ecole du Louvre [3] She studied drawing and painting in Paris with theatrical Russian exile Alexandra Exter. Cabrera lived in Paris for 11 years and returned home in 1938. After graduating from Ecole du Louvre, she did not become an artist as expected, instead moving back to Cuba to study Afro-Cuban culture, especially their traditions and folklore.

In 1936, while in Paris, she published her first book, "Cuentos Negros".[4]

For most of her life, Cabrera had a large interest in Afro-Cuban culture. She had been introduced to their folklore at a very young age by her Afro-Cuban nanny and Afro-Cuban seamstress. Three factors influenced her decision to study Afrocubanismo as an adult. The first influence was her experience in Europe, where studying African art became very popular. Secondly she was influenced by her studies in Paris, where she began to see the large influence that African art had on Cuban art. Thirdly she had as a companion Teresa de la Parra, a Venezuelan novelist and socialite whom she met while studying in Europe, and who enjoyed reading Cuban books with her. They often studied the island together.[5]

Cabrera and her lover and partner, historian

and paleographer María Teresa de Rojas, called

Titina (whom Cabrera met after Parra's death), helped restore one of Havana's most beautiful eighteenth-century

residences, the

During the late 1950s she continued to publish several books about Afro-Cuban religions, especially focusing on the Abakuá. Being a secret society, the Abakuás were reluctant to talk to her about their religion.[7] Since they did not accept women as members, Cabrera relied on the use of interviews to gain information for her book. It focused on the origins of the group, the myth of Sikaneke, and the hierarchy of its members. Somehow she managed to photograph their sacred drum, which is supposed to remain hidden at all times, to include within her research.[8]

Her career spanned decades before the Revolution, as well as many years after the revolution in Cuba. Although she was never schooled in anthropology, she takes a very anthropological approach to studying her subject matter. The main theme in her work is the focus on to the once-marginalized Afro-Cubans, giving them a respectable identity. Through the use of imagery and storytelling in her work, she seeks to retell the history of the Cuban people through the Afro-Cuban lens.[9] Generally, her work blurs the line between what society has deemed as "fact" and "fiction." [10] She attempts to pose ideas and theories that force one to question what they have been told. In Afro-Cuban Tales (Cuentos Negros De Cuba) she writes, "They dance when they're born, they dance when they die, they dance for killings. They celebrate everything!" (Cabrera 67). Here, she is connecting Afro-Cuban tales with African rituals because it is important to celebrate birth, passage to adulthood, marriage, and death.

She left the country in 1960 shortly after the revolution and never returned. She left as an exile, first going to Madrid and later settling in Miami, FL., where she remained the rest of her life. La Quinta San Jose house museum was dismantled by the Cuban government.

Cabrera received several honorary doctorate degrees, including one from the University of Miami in 1987. Cabrera describes her stories as "transpositions," but they went much further than a simple retelling. She recreated and altered elements, characters, and themes of African and universal folklore, but she also modified the traditional stories by adding details of Cuban customs of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Toward the last years of her life, Lydia Cabrera worked diligently to edit and publish the many notes she had collected during more than thirty years of research in Cuba.

The real reason why she left is still unknown. Some claim that she left because of the lifestyle the revolution was trying to instill. For many years, Cabrera had stated her dislike for the revolution and socialist-Marxist ideology.[11] Others claim she left because members of the Abakuá were hunting her down since she had made their secret society public.[12] Although the reason why she left is unknown, she never returned and spent the rest of her life living in Miami until her death in September 19, 1991.

María Teresa de Rojas died on January 25, 1987. On September 19, 1991, Lydia Cabrera died. Both women lie now in Woodlawn Park Cemetery, at Calle Ocho and 32nd Avenue, in Miami.

My published books: