Queer Places:

Cedarvale Bay City Cemetery

Bay City, Matagorda County, Texas, USA

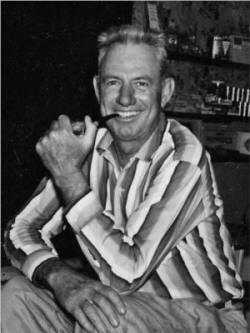

Forrest Clemenger Bess (October 5, 1911 – November 10, 1977) was an American painter and fisherman.[1] He was discovered and promoted by the art dealer

Betty Parsons.[2] He is known for his abstract, symbol-laden paintings based on what he called "visions."[3]

Forrest Clemenger Bess was a mystic and artist, who sought to fuse male and female in his life and work. In

small, but boldly painted, abstract pieces, Bess represented his visions, which, he believed, contained the

secret of immortality.

Beginning in 1960, Bess underwent surgical procedures with the intention of uniting male and female in his

own body. Frustrated by his failure to convince others of the validity of his belief that this fusion would

produce eternal rejuvenation, Bess lived in increasing isolation and poverty.

Although occasionally exhibited by major galleries and museums, Bess's paintings were largely overlooked

during his lifetime. However, since the late 1980s, Bess has gained posthumous recognition as one of the

most imaginative and original American painters of the twentieth century.

Forrest Clemenger Bess (October 5, 1911 – November 10, 1977) was an American painter and fisherman.[1] He was discovered and promoted by the art dealer

Betty Parsons.[2] He is known for his abstract, symbol-laden paintings based on what he called "visions."[3]

Forrest Clemenger Bess was a mystic and artist, who sought to fuse male and female in his life and work. In

small, but boldly painted, abstract pieces, Bess represented his visions, which, he believed, contained the

secret of immortality.

Beginning in 1960, Bess underwent surgical procedures with the intention of uniting male and female in his

own body. Frustrated by his failure to convince others of the validity of his belief that this fusion would

produce eternal rejuvenation, Bess lived in increasing isolation and poverty.

Although occasionally exhibited by major galleries and museums, Bess's paintings were largely overlooked

during his lifetime. However, since the late 1980s, Bess has gained posthumous recognition as one of the

most imaginative and original American painters of the twentieth century.

Bess was born on October 5, 1911 in Bay City, Texas, then a "rough and ready" community of about 18,000 people. Forrest's middle name was inspired by F. J. Clemenger, who had discovered the oil fields of nearby Clemville, where his father, Arnold Bess, worked as an oil driller. As his nickname "Butch" implies, Forrest's father was a hard working and hard drinking man, and he had little patience with his son's frequent absorption in dreams. On the other hand, his mother, Minta Lee Bess, was a strikingly beautiful and gentle woman, who encouraged Forrest's early indications of artistic talent. During most of Forrest's childhood, his family moved from one Texas oil boom town to another as his father wildcatted. Without a permanent home, the family often lived roughly in tents and other temporary shelters. However, by 1925, they had settled in Bay City, where Forrest attended high school. At the age of four, on the morning of Easter in 1915, Bess experienced his first vision. Upon a table in front of his bedroom window, he saw people moving through the cobblestone streets of a village under a sky full of multicolored light. As he got up in order to approach this scene, he was frightened by a tiger and a lion, sitting on chairs in his room. Throughout the later years of his childhood, visions--sometimes terrifying and sometimes comforting--occurred to him with increasing frequency. However, his friends remember him as a typical boy, lively and mischievous. In 1918, at the age of seven, he executed his first drawings by copying images of Greek and Roman mythological figures in an encyclopedia. In subsequent years, Bess avidly read about Greek and Roman mythology, and he produced numerous crudely executed oil paintings of classical subjects, such as Discus Thrower. In 1924, at the age of thirteen, he began to take private painting lessons from a neighbor in Corsicana. Utilizing images in encyclopedias, he created oil paintings of famous American landmarks and picturesque European villages. In later years, he maintained that he already had found in art a refuge from the harsh realities of life. By the time he entered high school, Bess felt that his personality was split into two virtually irreconcilable components: masculine and extroverted on one hand and feminine and introverted on the other. Although often lost in daydreams of ancient civilizations, he excelled both at football and school work. His parents hoped that he would enter West Point, but he failed the physical exam due to curvature of the spine. Although Forrest wanted to study art, he resolved to train for a career as an architect in order to please his father, who regarded art as insufficiently manly.

Between 1929 and 1931, he studied architecture at the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas (now Texas A & M University), but he did poorly in required courses in physics and mathematics. In 1931, he transferred to the University of Texas, where Professor Sam Gideon strongly encouraged his studies in world religions. However, Bess dropped out of university in 1933 without finishing the requirements for a degree. As he would do until he entered the military in 1941, Bess alternated sporadic work in the Beaumont oil fields with extended trips to Mexico. Although he later claimed to have spent many hours watching Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros at work, these muralists did not have any discernible impact on his art. In 1934, he opened a small studio in Bay City, and he had his first solo exhibition in the lobby of a hotel in that town. In 1938, he had a major one-person show at the Witte Museum in San Antonio, and he participated in group shows at the Museum of Fine Art, Houston, and at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Despite these early indications of possible future artistic success, Bess continued to live in destitution, making meager wages through hard labor in the oil fields and wandering off to Mexico whenever he managed to accumulate any spare cash. Beginning in 1947, Bess destroyed many of his earlier works, because he had come to regard them as derivative and uninspired. However, from the available evidence, it seems likely that, throughout the 1930s, he produced portrait subjects, still life objects, and landscapes in a style reminiscent of Vincent van Gogh, who already had become one of Bess's personal heroes because of the earlier artist's isolation and mystical view of the world. Sweet Potatoes (1934, private collection) probably is typical of Bess's paintings of the 1930s. Among the features that recall paintings by Van Gogh are the flattened spatial perspective; heavily outlined, distorted shapes; thickly applied oil paint, roughly marked by coarse brushes; and the bright, unrealistic coloring. During the 1930s, he also occasionally experimented with abstract compositions.

In 1941, Bess enlisted in the U.S. Army and initially proved to be a model soldier; he quickly rose to the rank of captain in the Corps of Engineers. He took great pride in the commendation which he received for his camouflage designs, but he felt very frustrated when the army decided to shelve his plans for financial reasons and assigned him to teach bricklaying to new recruits. In 1946, while still in the army, Bess experienced a series of exceptionally terrifying visions, which left him feeling physically incapacitated, and, subsequently, he suffered a complete mental breakdown. During treatment at the Veterans Administration Hospital (now Audie L. Murphy Memorial Veterans Hospital), San Antonio, a psychiatrist helped to make him aware of the psychological and spiritual significance of the colored shapes that he saw shortly before falling asleep. Near the end of his therapy, he enjoyed working as a painting instructor at the hospital. Upon leaving the service, Bess set up a small gallery and frame shop in San Antonio, and he became a prominent figure in the local art scene. Nevertheless, in 1947, for reasons that are uncertain, Bess left San Antonio and moved to the site of his family's bait fishing business at Chinquapin (near Bay City) on the Gulf coast in southeast Texas.

Barely supporting himself by catching fish which he sold as bait, Bess lived in primitive conditions. With the hull of an old tugboat and copper sheets from the hull of a ferry, he built a shack, which he covered with layers of tar and oyster shells for insulation. Although technically a peninsula, the barren strip of land on which Bess resided often was separated from the mainland by water and accessible only by boat. Not surprisingly, these physical circumstances exacerbated Bess's sense of psychological isolation from others. After his father's death in 1954, he had little contact with other individuals. Bess found the peninsula both frightening and inspiring. Writing to Betty Parsons, he explained: "it has a ghostly feeling about it--spooky--unreal--but there is something about it that attracts me to it--even though I am afraid of it." In the harsh environment of the peninsula, Bess devoted himself to the exploration of the unconscious world, revealed by his visions, which now recurred on a regular basis. Instead of the complex and often frightening scenes that he had previously witnessed, his visions now were reduced largely to simple, vaguely geometric shapes, which seemed to hover inside his eyes. Until he stopped painting in 1974, he sought to record the images that appeared unbidden to him. He insisted that he made no effort to modify or elaborate his visions in any way. "To do so would be hypocritical and untruthful," he commented. "Many times the vision is so simple--only a line or two--that when it is copied in paint I feel 'well gosh, there isn't very much there, is there?'" Most of Bess's mature works--such as Untitled no. 14 (1952) and Untitled no. 11a (1958)--consist of simple shapes, such as lines, circles, and crescents, against a flat or vaguely atmospheric background. In some pieces, such as Warrior (1947) and the provocatively named The Dicks (1946), Bess utilizes shapes that seem to have emphatic homoerotic connotations. Corresponding with his growing fascination with androgyny, many of his paintings combine male and female signifiers. For example, in #1 (1951), phallic forms frame a space filled with inverted triangles (a symbol of female fertility in many cultures) and vaguely flame-like shapes. However, it should be emphasized that one cannot be too precise in interpreting Bess's mature work. Thus, Stuart Preston noted in a New York Times review of his 1962 show at Betty Parsons Gallery: "Any attempt to establish visual or symbolic identifications in the shapes that grow in the inscrutable compositions will come to grief. Better just to respond to them." Even without deciphering all the possible meanings that the shapes may have had for the artist, one can appreciate the intensity of the experiences that inspired the artist to record these images. Contributing to the immediate and powerful impact of Bess's work is the artist's lively and bold handling of paint. Although he generally applied paint heavily and roughly, he occasionally created lush and overtly sensual effects. He usually employed strong, deeply resonant colors, often choosing ones that contrasted strongly with one another. Belying their powerful psychological presence, most of his paintings measure less than a foot square. Although most of his mature work is abstract, he did produce some highly stylized landscapes. In Seascape with Sun (ca 1947, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago), he evoked his profound interactions with the Gulf coast area; he represented the sea as a turbulent mass of black waves beneath an intense red sky with a bright orange sun. In Homage to Ryder (1951, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago), he paid tribute to the earlier American visionary painter, Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917), through the depiction of a landscape with brilliant light, fading at the horizon.

In 1949, hoping to find a broader audience for his work, he sold over forty of his older paintings for ten dollars each in order to raise money to travel to New York to find a dealer. Betty Parsons, who constantly demonstrated a willingness to promote highly distinctive and unconventional work, received his work warmly and agreed to serve as his dealer. Through her representation of many of the leading figures of the emerging Abstract Expressionist movement (including Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman), Parsons had already established her gallery as one of the leading venues for contemporary art in New York during the 1950s and 1960s. Bess's commitment to visualizing the unconscious related his work to that of the leading Abstract Expressionists. However, the diminutive scale and obscure symbolism differentiated his paintings from their monumental and more extroverted works. In December 1949, Parsons gave Bess a one-person show, as she did again in 1954, 1957, 1959, 1962, and 1967. Helped by the prestige of his association with Parsons, Bess also received solo exhibitions at galleries and museums in other cities (including, among others, Philbrook Art Center, Tulsa, 1952; André Emmerich Gallery, Houston, 1958; Stanford University, 1958; Contemporary Art Museum, Houston, 1962). Despite the good reviews earned by these shows, Bess was able to sell very few paintings, and he had to depend primarily upon his bait business for his livelihood. The time and energy that he had to devote to catching shrimp severely restricted the quantity of his later artistic production. Therefore, from the mid-1940s onwards, Bess produced only approximately one hundred paintings.

During the 1950s, Bess became increasingly preoccupied with the severe split that he perceived in his own psychological makeup. In letters to Parsons, Bess explained that he felt deeply troubled by the conflict between "personality # 1," which he praised as masculine and aggressive, and "personality # 2," which he belittled as weak and effeminate. Most of Bess's acquaintances in Texas assumed that he was a homosexual, unable to do deal with the social stigma then widely associated with this sexual orientation. However, Bess believed that his inner turmoil had other sources. Through a profound mystical experience in the summer of 1953, Bess became convinced that the shapes that he had been recording in his paintings contained clues to the resolution of the conflict between his two personalities. To enhance his understanding of these forms, Bess corresponded at length with Carl Jung and other leading specialists in the psychological and spiritual significance of symbols in world cultures. Following suggestions made by these scholars, Bess read extensively in the fields of psychology, anthropology, and world religions. This research helped him to understand that the shapes in his visions and paintings corresponded with symbols for gender identities in many world cultures. Referring to theories developed by various cultural anthropologists, he determined that his visions encouraged the synthesis of male and female. By the late 1950s, he became convinced that he was the prophet of a new world order based on androgyny. Further, he believed that the physical fusion of genders within his own body would not only relieve his profound anxieties but also reveal the secrets of immortality to the human race as a whole. Determined to establish the truth of his convictions, Bess utilized surgery to create an opening, or fistula, at the junction of his penis with the scrotum. He believed that the insertion of another penis in this artificially created opening would produce an intense orgasm that would lead to spiritual awakening and, hence, to eternal rejuvenation. Although the results of the surgery were verified, the precise details of the procedures that Bess underwent in 1960 and 1961 remain unclear. Bess is supposed to have recorded full information on the surgery in a notebook that was lost in 1968 by the medical editor of the Washington Star to whom Bess had entrusted it in the hope of securing its publication. It is known that a local physician, R. H. Jackson, was present at the operations, but many commentators think that Bess may have performed them himself. Dismayed by horrified reactions to announcements of his transformation, Bess became increasingly withdrawn and depressed. Furthermore, numerous physical and psychological problems plagued him during the later years of his life. His nose had become cancerous, and he had to have a substantial part of it removed in 1966. Because of his skin cancer, he was forced to retire from his bait business in Chinquapin and move to a house in Bay City, where he could be cared for by relatives. In 1973 and again in 1974, Bess was arrested for disruptive behavior in public. After he suffered a stroke in 1974, his brother committed him to San Antonio Mental Hospital and, subsequently, to Bay Villa Nursing Home, where he lived until his death on November 11, 1977. Despite the difficulties of his later years, Bess continued to paint until 1974, and his artistic powers remained undiminished by his harsh experiences. In 1988 and 1989, major retrospective exhibitions of his work at Hirschl and Adler Modern Gallery, New York; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; and the Museum Ludwig, Cologne helped to stimulate interest in his work. Since then, his unique, poetic works belatedly have begun to receive the critical acclaim that they merit.

My published books: