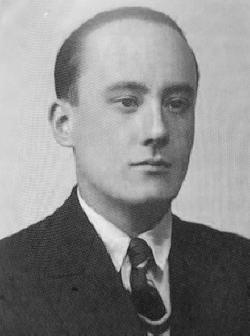

Daniel Guérin (May 19, 1904 – April 14, 1988) was an activist in the French

labor and socialist movements. After a long career, Daniel Guérin "came out" as a

homosexual in his late sixties and for the remainder of his life worked to fuse gay liberation with left-wing

politics.

Daniel Guérin (May 19, 1904 – April 14, 1988) was an activist in the French

labor and socialist movements. After a long career, Daniel Guérin "came out" as a

homosexual in his late sixties and for the remainder of his life worked to fuse gay liberation with left-wing

politics.

Frédéric Martel dubbed Daniel Guérin "grandfather of the French homosexual movement," but the term is

misleading. Although it is true that, as one journalist has written, he "dedicated his life to the love of boys

and to revolution," Guérin did not actually become involved in homosexual politics before the early 1970s.

Until then he kept his sexual orientation strictly private for fear that it would discredit him with the

notoriously homophobic French political left.

Guérin was born on May 19, 1904 into a well-to-do and well-connected Parisian family noted for its liberal

and humanist principles. As a young man in the politically charged atmosphere of the 1920s and 1930s, he

rejected his privileged background to embrace the cause of proletarian revolution. He later attributed his

radicalism at least in part to his sexual adventures with virile working-class men. "It was there, in bed with

them, that I discovered the working class, far more than through Marxist tracts," he admitted in the 1980s.

After study at Sciences Po' (the prestigious Free School of Political Sciences) in Paris in the early 1920s,

Guérin took a job as clerk in his family's publishing firm before embarking on a brief career in journalism in

1930 and then becoming a trade-union and political organizer.

In the late 1920s and the 1930s he traveled extensively in the French colonies in the Middle East and South-

East Asia, an experience that turned him into a lifelong enemy of racism, colonialism, and imperialism.

Guérin also visited Germany, where he witnessed first-hand the threat posed by Nazism. "Fascism is

essentially offensive," he warned, "if we remain on the defensive, it will annihilate us." During World War II,

however, he refused to choose between the "imperialist bloc" (the Allies) and the fascists, and instead

worked underground with a clandestine group of Trotskyites.

After the war, he lived briefly in the United States (1946-1949), where he was shocked by the plight of

African Americans. In the 1960s he supported the Algerians who were fighting for their independence from

France.

In sum, Guérin was a consistent leftist: a Marxist and Trotskyite with marked anarchist tendencies.

Guérin's homosexuality was always a major part of his life, even though he married in 1934. (Today his only

child, Anne Guérin, continues to promote her father's ideas, and her son, Faïz Henni, maintains a website

dedicated to his grandfather's life and work.) Despite a facade of heterosexual respectability, Guérin--like

his own father before him--pursued homosexual relationships until the very end of his life. He began his last

serious love affair at the age of seventy-seven--with a young man of seventeen!

Guérin started writing in defense of sexual freedom and homosexuality in the early 1950s, but did not

admit to his own homosexuality until the late 1960s, after the "events" (strikes and riots) of May 1968

initiated a liberalization of French moral values.

He later described the "cruel dichotomy" of those previous years during which "I felt myself cut in two,

voicing out loud my new militant [political] beliefs and feeling myself by necessity obliged to hide my

private [sexual] tendencies." He blamed homophobia on the middle class, which, he claimed, promoted the

family and family values as the basis of the established social and political order.

"The revolution cannot be simply political," he argued. "It must be, at the same time, both cultural and

sexual and thus transform every aspect of life and society."

Active in the Homosexual Front for Revolutionary Action (Front Homosexuel d'Action Révolutionnaire, or

FHAR), founded in March 1971, Guérin was soon disappointed by the young gay liberationists who set out to

shock and provoke society instead of organizing effectively to change it. He considered most of these gay

radicals to be politically inept, ideologically naive, and "often very stupid."

He embraced the youthful insolence of FHAR enough to strip naked at one general assembly in order to

make a point, but remained sufficiently concerned by the lack of order to draft a plan, entitled "For the

constitution and organization of a political current in the heart of FHAR," intended to create a semblance

of structure and to provide the movement with concrete political goals. It had no effect whatsoever.

Guérin also rejected the consumerist gay culture and "the superficial pursuit of pleasure" that emerged in

France the 1980s as "a million miles from any conception of class struggle." He nevertheless continued

contributing to the French gay movement by giving interviews, writing articles for the gay press, and

speaking out in defense of gay rights.

He maintained that "homophobic prejudice" could not be defeated through "reformist" means, but "like

racial prejudice, only by an anti-authoritarian revolution." Homosexual liberation "will be total and

irreversible only if it is achieved within the context of social revolution."

Guérin published dozens of books and hundred of articles on such topics of vital concern as fascism and

capitalism (which he believed linked), racism, militarism, and colonialism. He also wrote favorably about

anarchism, the American labor movement, the revolutionary ideas of Rosa Luxembourg, the African-

American fight for equality, and the Kinsey report on human sexuality. He even brought out

autobiographical work, including Autobiographie de jeunesse (1965), Le feu du sang: autobiographie

politique et charnelle (1977), and Son testament (1979).

Yet Guérin considered his most important work--the one worth remembering after his death--to be a twovolume

historical study of the popular movement in the French Revolution, The Class Struggle under the

First Republic, published in 1946. Guérin saw the political and social agitation by urban artisans and wageearners

during the French Revolution as the forerunner of the proletarian revolutions of the twentieth

century. The historical profession greeted the book with little enthusiasm.

Guérin is remembered today chiefly for his uncompromising stand as a political, labor, and gay militant.

In 1975, Pierre Hahn, another pioneer militant, wrote to Guérin: "More than to anyone else, homosexuals

are grateful to you . . . for everything you have done for them. . . . The most valuable thing you have done

is a life's work that is both political (in the traditional sense) and sexological: it's [your books like] The

Brown Plague [on fascism] plus Kinsey [on the Kinsey Report]; it's Fourier [on the nineteenth-century

radical thinker] and the texts against colonialism: finally it's you yourself."

My published books:

BBACK TO HOME PAGE

- Guérin, Daniel (1904-1988)

by Michael D. Sibalis

Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc.

Entry Copyright © 2006 glbtq, Inc.

Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com

- Gay and Lesbian Library Service, edited by Carl Gough and Ellen

Greenblatt

Daniel Guérin (May 19, 1904 – April 14, 1988) was an activist in the French

labor and socialist movements. After a long career, Daniel Guérin "came out" as a

homosexual in his late sixties and for the remainder of his life worked to fuse gay liberation with left-wing

politics.

Daniel Guérin (May 19, 1904 – April 14, 1988) was an activist in the French

labor and socialist movements. After a long career, Daniel Guérin "came out" as a

homosexual in his late sixties and for the remainder of his life worked to fuse gay liberation with left-wing

politics.