Husband Steve Wheeler

Queer Places:

202 N Spruce St, Wichita, KS 67214

Dale

Franklin Schultz, Jr (1943 - December 30, 2001) was the cofounder and

publisher of the regional gay newspaper The Rock River News of Rockford,

Illinois.

Dale

Franklin Schultz, Jr (1943 - December 30, 2001) was the cofounder and

publisher of the regional gay newspaper The Rock River News of Rockford,

Illinois.

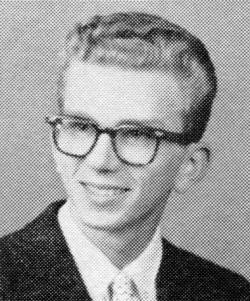

He attended Wichita High School, class 1961, where he was a Pen Pals President. His husband was Steve Wheeler, a gay rights activist and the editor of the Rock River News. They married on June 16, 1991. Steve Wheeler's papers, collected together with those of Bruce McKinney, documents how he had left Wichita with Dale Schultz to move to Illinois. Additionally, Wheeler’s papers document not only his life, but also much of Dale Schultz’s through personal letters, journals, and photographs. Wheeler’s papers expanded with a November 2010 acquisition, to include numerous magazines, as well as his personal journals and letters following the breakup of Dale Schultz and Wheeler. The addition also includes a large number of photographs. Both the letters from Schultz and the photographs are important aspects of the narrative that detail Schultz and Wheeler’s relationship, first while committed partners, and later when close friends.

On February 27, 1989, Schultz learned that he had tested positive for HIV while his partner of three years, Steve Wheeler, had tested negative. From the beginning, Schultz took ownership of the illness, writing in his journal, “I don’t feel hate. I was not playing safe at my early part of gay life, didn’t know better. I’m not sorry for what I have done, I know I’m a person now. I know I’m gay.” At the time, Schultz took the diagnosis as an immediate death sentence, and over the next six weeks wrote several entries in his journal expressing his fears and frustrations. The narrative recounts his family’s abandonment when he came out and divorced his wife in 1987, and it illustrates the renewal of Schultz’s anger as he confronted his family’s response to his contracting HIV. His mother told him that HIV was God’s punishment on him for being gay. His sister , initially too overwhelmed by the news to respond, eventually failed to provide support, following her religious views about homosexuality. After parting with Wheeler in 1996, Schultz moved to Florida where he lived until approximately 2000.

A series of letters in 1996 from Schultz to Wheeler following their breakup trace Schultz’s feelings of sorrow, regret, and hope as he examines the good and the bad in their relationship. In a card written to Wheeler on June 22, 1996, Schultz writes, “Yesterday you should have arrived at Faerie Land. Today should start a new beginning for you. I’m really trying to let go but its [sic] so damn hard. I know at some point in my life I want to feel free and have the free spirit that I need to have. It will take time and I know I can do it.” In an attached undated letter, Schultz writes, “Steve, The day you left, the coffee pot broke, the clock in the living room stopped. You left at 11:00 AM, 10 June 1996. I talked to Bertie that night, also my sister, who I told to go to hell. I didn’t want contact with her. And I fell to pieces.” Schultz’s narrative describes how his life has been broken by the couple’s separation. Wheeler has the promise of a new beginning while Schultz has been left behind in their apartment, where the surroundings are a constant reminder of his former partner. Schultz is unable to find relief from the anguish that he feels at the loss of his lover, and in response, he lashes out at others, specifically his sister in this instance.

Over the next month, Schultz’s anger begins to emerge in letters to Wheeler. In a letter dated July 30, 1996, he writes : Another thing — the sideboard, I told you that I was sure you would need money sometime and that you could sell it to get some. Don’t put a guilt trip on me to say I sent it with you to remind you of me. Not true, and not true with anything you took in the truck. I have enough memories of you in my head. I don’t need the material things for that. That is why a lot of things are being packed here at my place. I know I will not get back together with you and I don’t want to.

Schultz writes almost daily beginning with the card dated June 22, 1996 . Many of the letters refer to the lost relationship with occasional details about his day, whether he walked to the marsh to check on some planted flowers, or checking on photographs that had been developed. The above letter is the first point in the series when Schultz admits that the two have no future together. Prior to this he acknowledges why the two parted and expresses changes that he’s going through, explaining that he is evolving as a man and potential partner, possibly hoping to entice Steve to return. The July 30th letter is a climactic point in the archival narrative of Schultz and Wheeler’s relationship as Schultz accept s the finality of their breakup.

Schults returned to Wichita, to live with Steve Wheeler and Wheeler’s partner, Jay Zander, beginning of the 2000s. On December 30, 2001, twelve years and ten months after being diagnosed with HIV, Dale Schultz died from AIDS related complications in Wheeler’s care. Schultz, who had written extensively in his journal for over two months during 1989, stopped for ten years. When he returned to writing in 1999, he makes no mention of the disease, having come to accept it as a part of his daily life.

However, photographs within the McKinney Collection document Schultz’s decline over the last thirteen years of his life. As the photographs progress toward the end of the millennium, Schultz begins to age within the images, his hair graying and his body thinning. The photographs also show some of those who had previously abandoned him reenter ing his life. Prior to his death, Schultz developed a relationship with his children and his grandchildren.

Schultz’ s description of his HIV diagnosis, and subsequent life, challenge the perceptions of the illness. The images of Schultz in the collection do not show the emaciated, hollow - eyed “victim” that was so apparent in the media in the late 1980s and also present in the Bruce McKinney Collection as a representation of people living with AIDS prior to 1990. Instead, Shultz creates visibility that queers the mass public’s view of the illness. And while Schultz’s journal initially expresses his fears at having the disease, it does not describe his rejection from society. Instead, Schultz’s words demonstrate that the diagnosis does not appear to be the death sentence that he had originally believed it to be. After learning of his status, Schultz lived for almost thirteen years, allowing him time to experience a break - up with Wheeler, new lovers, a renewed relationship with his family, and time to grow accustomed to his HIV status. In other words, his experience with HIV/AIDS contradict s his own beliefs. Schultz’s person al insight creates a character with whom many readers can identify, not just as a person with AIDS, but as a person living in fear of the unknown. Schultz creates a space through his personal narrative and photographs that touches the reader’s emotions, as he becomes an endearing, sympathetic character.

Jay Zander attended the 2000 march in Washington, D.C., with Wheeler. An AIDS patient, Zander thought it important to march to show people how "normal" gays were. "These are just regular people," he said. "They live their lives, they hurt, they love, they cry, they laugh."

Schultz died of complications of AIDS on December 30, 2001. Wheeler died in 2003.

My published books: