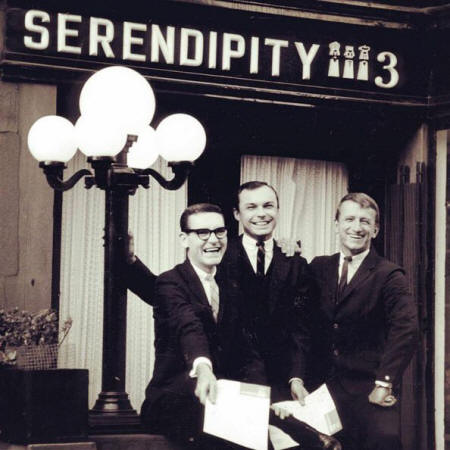

Partner Stephen Bruce

Queer Places:

3807 W 10th St, Little Rock, AR 72204

Serendipity 3, 225 E 60th St, New York, NY 10022

Calvin Lamar Holt (May 14, 1925 - June 7, 1991), together with Stephen Bruce and

Patch Carradine, opened Serendipity 3, a dessert boutique, in 1954.

The three encouraged Andy Warhol to hang his

drawings on the walls. The astute vision the three men shared would soon be

recognized by crowds lining the block for their frozen hot chocolate, and the

chance to catch a glimpse of a celebrity amid the Tiffany-shaped décor. Today,

after 50 years, the crowds keep coming.

Calvin Lamar Holt (May 14, 1925 - June 7, 1991), together with Stephen Bruce and

Patch Carradine, opened Serendipity 3, a dessert boutique, in 1954.

The three encouraged Andy Warhol to hang his

drawings on the walls. The astute vision the three men shared would soon be

recognized by crowds lining the block for their frozen hot chocolate, and the

chance to catch a glimpse of a celebrity amid the Tiffany-shaped décor. Today,

after 50 years, the crowds keep coming.

Calvin Lamar Holt was born on May 14, 1925 in Hazen, Arkansas. He studied acting at the Goodman Memorial Theater in Chicago and modern dance with Jose Limon in New York. He acted and danced on television, in Latin Quarter revues and in Broadway shows including the 1955 production of "Catch a Star!"

Holt and his partner, Stephen Bruce, presided over Serendipity 3, a lively cafe and boutique, since it opened in 1954. Its quirky specialties range from zen hash to frozen hot chocolate, and its whimsical merchandise is framed by original Tiffany lamps and other antiques. Favorite fare among the cafe's celebrity-sprinkled habitues are three-egg omelets filled with cavier and sour cream, Aunt Buba's sand tarts and lemon ice-box pie. Their formulas were revealed in "The Serendipity Cookbook," written by Holt and Bruce with Pat Miller and published in 1990 by Wynwood Press.

Stephen Bruce, Calvin Holt and Patch Caradine opened the cozy, quirky, antique-filled cafe called Serendipity 3 on a quiet stretch of Second Avenue. The name came from Caradine, a bookkeeper with literary aspirations whom Bruce calls a collector of words. Caradine found serendipity in a London Times crossword puzzle; the 3 refers to the founding trio. The restaurant, which was beloved by Andy Warhol, Marilyn Monroe and a spate of Hollywood stars after them, has survived partly thanks to its signature, over-the-top dessert, Frrrozen Hot Chocolate, and partly because it's a storied palace of cheeky joy where lingering over goblets of slushy chocolate and whipped cream is the main draw. The original concept was an antiques shop with a cafe in back. Bruce, who moved to the city from upstate New York after high school, was a window dresser and aspiring designer with a flair for antiques and finding things, as he describes it; Holt, a dancer, and Caradine were from Arkansas, and brought to the table their Southern charm and their mothers' pie recipes. After finding the small basement space on Second Avenue, the trio went upstate to Hudson, N.Y., to source antiques. The only thing available to us were Tiffany glass shades, Bruce says. They were out of fashion and no one wanted them. We saved them from the children of the antiques dealers, who were putting them in the trees and throwing rocks at them. Those art nouveau shades, with their colored-glass floral mosaics, became a calling card for the restaurant, and the white cafe tables are still washed with their kaleidoscopic light. Next came a visit to Little Italy, where they bought a discounted espresso machine, something of a novelty at the time. They opened with cake and pie and cappuccinos; an espresso drink was 30 cents, and desserts, chocolate pecan pie, rum cake and sand tart cookies, went for 75. The menu expanded when they realized that they couldn't survive, financially, on cake, cappuccinos and hospitality alone.

Andy Warhol and Stephen Bruce at Serendipity 3, circa 1962.Credit...John Ardoin

Serendipity III

From the beginning, Serendipity's guiding principal was whimsy: knickknacks and antiques were everywhere, hanging from the ceiling and along the whitewashed walls. (Visiting now, you feel like you're in a more-chic reference photo for the original TGI Friday's.) When they outgrew the space, they moved around the corner to East 60th Street, where the restaurant is still located. Soon they started serving foot-long hot dogs and caviar omelets, the sorts of things that would be called Instagram bait had they opened in 2019. Serendipity's menu prizes extravagance and awe just as much as it deals in comfort food, and the people running it have always understood the value of a well-placed gimmick. In the entryway of the store sit the restaurant's three Guinness world record certificates: the world's most expensive milkshake ($100), the most expensive hot dog ($69) and the most expensive hamburger ($295). What makes all this lovable is that the restaurant seems to be in on the joke. Everyone's having fun here, and anyway, what would you expect from a restaurant where people have paid to get married in bathtubs full of frozen hot chocolate? (For the curious, the tubs were broken down and then assembled in the dining room; the wedding was officiated by the television host Joyce Brothers and the porn actress-turned-television host Robin Byrd; the couple brought a change of clothes for the reception that happened upstairs; the wedding took place on Valentine's Day.) That menu expansion also birthed the Frrrozen Hot Chocolate. The original recipe called for 14 different kinds of chocolate melted together and blended with ice, and each batch was handmade; now, the restaurant has an outside company prepare the mix. The result, served in a footed cut-glass desert bowl with a straw, is a gleeful experiment in just how rich chocolate can be: icy and barely crunchy and thick, topped with a glob of whipped cream and a layer of thin chocolate curls. In Serendipity's 65 years of business, it has become something of a New York landmark. It's a place famous for celebrity sightings and a place unashamed to publicize those sightings. It inspired a 2001 movie of the same name, starring John Cusack and Kate Beckinsale, who play characters who bond over a glass of frozen hot chocolate. The restaurant's cookbook includes an introduction written in exactly 100 words by Cher. Service is hyper-attentive and accommodating; as Pamela Tobias, a 48-year-old integrative health coach, says, They were probably the original place of special requests. Tobias has been going to Serendipity since the '70s. Now she goes with her girlfriends, and each has their own personal hot chocolate order. We're always there hanging out, chatting, eating our desserts, sometimes late at night, she says. Never with a guy, though! The allure of such a place comes partially from the food, of course. As Jonn Jorgenson, who has been a Serendipity waiter since 1993, explains, Comfort food and a little bit of decadence is never going to go out of style. But it's also about the way the restaurant has leaned into its self-mythologizing, building a little world that lures newcomers with sugary treats and boasts about all the people who have been coming here for decades. Jorgenson relishes telling the story of Marilyn Monroe busting out of her dress at a news conference with the Actors Studio in the dining room and hiding in the women's bathroom until Bruce could come sew her back in. Any time a woman goes, Oh my god, that bathroom is teeny tiny! I say, Yeah, it was tiny enough for Marilyn to be sewn back into a dress she had come out of! This a celebrity haunt with a total lack of exclusivity, and a Lewis Carroll-like fun house dedicated to G-rated pleasures. When I try to explain it to people who haven't been there, I'm like, Well, really, it's a principality, says Jorgenson. It was started by three men who refer to themselves as the princes of Serendipity. In a New York that is being gradually stripped of its whimsy, participating in the tradition that is Serendipity is a luxe little comfort. Yes, it's kitschy, but this is kitsch with soul, kitsch whose great desire is for you to enjoy it. There's a little doll of Andy Warhol, which he made, hanging from the ceiling. There's a disco ball a few feet away from it. The menu looks like the playbill for a Vaudeville show. It's the sort New York place you want, immediately and desperately, to protect, even on your first visit.

As a director of the Association of East Side Communities, Holt challenged the proposed development of the Queensboro Bridge area.

He died on June 7, 1991 in New York, New York. He was 66 years old and lived in Manhattan. He died of complications from heart bypass surgery, a family spokesman said.

My published books: